Elizabeth Gilbert discusses “The Signature of All Things” Tuesday, Oct. 1, at 7 p.m. at Barnes & Noble Union Square.

Elizabeth Gilbert discusses “The Signature of All Things” Tuesday, Oct. 1, at 7 p.m. at Barnes & Noble Union Square.

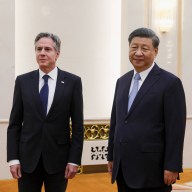

Credit: Getty Images

After writing one of the most revered books of the last decade, one might assume the pressure would be on Liz Gilbert to somehow top the massive success of her 2006 memoir, “Eat, Pray, Love.” But Gilbert’s not having any of that.

“The pressure for me wasn’t even ‘how do I beat that?’ Because you can’t beat that,” says the author of the new fiction tome “The Signature of All Things.” “That was a ridiculous tsunami of a phenomenon. There’s no way to do it again, and it doesn’t have to happen again.”

Without those anxieties, Gilbert allowed herself to explore fiction, a genre she had left 13 years earlier. The writer went back to her roots — and explored a whole bunch of literal roots — for her new botany-focused novel, “The Signature of All Things.” “Signature” follows the story of Alma Whitaker, a gifted plant scientist who wrestles with her beliefs after falling in love with a man whose passions lie in the mystical and divine. In the story, which takes place in the 19th century, Gilbert takes her characters on a cross-country journey not unlike the one she embarked on for her famous memoir.

What drew you back into fiction?

I missed it! It’s where my heart is. Let me begin by just saying I have no regrets whatsoever about having written “Eat, Pray, Love” — obviously it’s been a great move in my life. [But] my intention always has been to be a fiction writer. I was well on that path with my first two books, and then I really kind of needed my writing in my thirties for something else — I needed it to help me sort some things out. And I used my writing exclusively for that purpose for the entirety of my thirties. I got everything sorted out as much as anybody ever can. I just wanted to go back to what I had always loved, and I wanted to go back in a big way as a celebration of what “Eat, Pray, Love” had brought me, and I have the resources now to take time to do the book and to travel where I needed to travel for research. I really wanted honor that by going big, and by writing the kind of book I’ve always wanted to read. A nineteenth century epic.

Was it easy to get back into that groove, or was it harder than you remembered?

It was the opposite of that! I was so daunted by what I was taking on because I hadn’t written fiction in 13 years, hadn’t written a short story, nothing. So I had not only lost my confidence that I knew how to write fiction, I had also lost my confidence that I knew why we write fiction. I sort of had forgotten, what do you do this for? And then I had taken on material that I’m not familiar with: I’m not a botanist, I’m not a historian.

You could be now though, right?

Definitely not! But I learned enough to fake it! But taking all that on was so intimidating that I over-prepared. Now I know that that’s how you do it. The more rigorously you over-prepare, the better time you’re going to have when you come to write. … And once I started to write, it was delicious, it was so much fun! It’s almost like I had only remembered the hard parts about writing fiction. I had forgotten the joyful parts.

How long were these characters floating around in your head?

It’s like developing a photograph very slowly. I had only the vaguest ideas: power, intellectual mother, ambitious father, troubling, cold sister, complicated husband. And an intellectual, inspiring, energetic heroine. It’s during the research that the characters come to you; you start to hear, as you’re reading, I don’t know, some nineteenth-century manual on greenhouse construction, it brings your character to you. … From the beginning I knew Alma very well. But I have to say I loved writing [her father] Henry so much; it’s so fun to write a character who has only one motive, and that is to conquer.

Is there any bit of anyone in your life that you based these characters on? Even yourself a little?

Not deliberately, but I’ve quoted this one before, but a friend of mine once told me, “When you write memoirs, you’re actually writing fiction. And when you write fiction, you’re accidently writing memoirs.” Consciously, when you’re writing a memoir, you’re sort of inventing yourself. And you’re so unselfconsciously writing fiction that you’re accidentally revealing yourself. I would have said at the beginning that Alma and I had nothing in common and now I laugh because all of my friends are like, “Well there you are! We know that person!”

Having gone from laying everything about yourself bare, to keep yourself out of it must have been a different challenge.

It was. And it was fun. But I don’t know how well I kept myself out of it. I think people who know my writing will recognize my themes in there, the same stuff I’ve always written about: exploration of self versus other, how we define ourselves, who our obligations are to, what happens when we finally leave. All of those questions — mysticism versus rationalism — it’s all me.

Your characters do a lot of traveling in this book. Did you want their experiences seeing the world to mirror your own?

I know what it feels like to go through some of the things they went through. I know the loneliness—like the scenes of Alma wandering around Amsterdam at night and being both frightened and excited—that stuff is so familiar to me. … Suddenly feeling like, “I don’t know anybody and I’ve got nothing!” That’s something I think every traveler has encountered. It’s funny because initially my intention with this book that Alma would never leave [her estate]. I wanted to explore what women with tremendous intellects do in order to discover the world when they aren’t allowed to travel. That was my original theme for the book and I just couldn’t leave her there for her whole life!

It sounds like this story was almost screaming to get out of you.

It was more like, do this book so you can do the next one. I think in a weird way — people always talk about writer’s block — the thing that’s always gotten me through writer’s block is the idea that “just finish this book so you can start the next one.” The next one is always the most exciting one. The one you’re working on is never the exciting one. The one that’s coming — that’s the exciting one. You have to keep that on the horizon, that you’re chasing but cannot catch. And you don’t want to ever catch it, you want to keep chasing it.