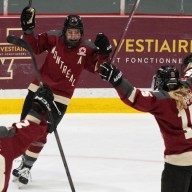

Michael B. Jordan (carrying Ariana Neal) plays real-life police casualty Oscar Grant in “Fruitvale Station.”

Michael B. Jordan (carrying Ariana Neal) plays real-life police casualty Oscar Grant in “Fruitvale Station.”

Credit: The Weinstein Company

‘Fruitvale Station’

Director: Ryan Coogler

Stars: Michael B. Jordan, Melonie Diaz

Rating: R

3 (out of 5) Globes

“Fruitvale Station” closes with footage from New Year’s Day seven months ago, with an anniversary eulogy for the man the film portrays: Oscar Grant, a 22 year old senselessly killed by a police officer only fifteen minutes into 2009. (Hopelessly this doesn’t sound too similar to another senseless death.) The many mourners seem to treat him as a kind of folk hero. But “Fruitvale Station” tries hard to treat him as a person — just a guy. “Station” spans just over the last 24 hours of his life, and if it weren’t for the actual cell phone footage of the concluding incident that opens the film, it could seem to be just another, mildly momentous movie day-in-the-life.

Grant is played by Michael B. Jordan, known either/both as Vince Howard on “Friday Night Lights” and Wallace on “The Wire.” Jordan has an easy likability to him, a sweet intelligence that can sometimes drift into something darker. Grant is a martyr, but not a saint: He’s done jail time, presumably (we’re never told) for dealing, which he still hesitantly does. It’s suggested he’s recently cheated on his girlfriend Mesa (Melonie Diaz), with whom he has a four year old daughter (Ariana Neal). He’s been laid off from a supermarket job for two weeks due to chronic lateness, a fact he hasn’t told his family. The only time the movie leaps away from this single day — for a jail-set flashback that half exists to give Octavia Spencer, as his mom, a scene to chew on — we see Oscar shift from genuinely good-natured to hardened perp, swapping smack with another con, a monster lurking there when prodded.

Jordan deserves any of the many accolades that have come, and will come, his way, and it’s the most interesting part of a movie that sometimes gets stuck on indie cliches. A scene where Oscar tends to a dog just mowed over in a hit-and-run (he’s sensitive, see?), plus all the talk of finally, at long last turning his life around can seem stock, though the last part is allegedly accurate. (Ditto, incredibly, that this did happen on his mother’s birthday. Sometimes life does imitate Sundance movies.) But first-time filmmaker Ryan Coogler, who was Oscar’s age when this occurred, doesn’t buy into his protagonist as something more than he is. Nor does he treat him as mere victim. Oscar seems to be little more than a casualty of fate. Coogler doesn’t delve into potential racism with the white cops who beat and shot him, but portrays the incident (to the letter, reportedly) as a situation that went madly out of control, even if it’s not exactly blameless. It brings him back to life, (mostly) warts and all.