Brad Pitt gets to play to his relaxed, gravitas-oozing movie star strengths as tank crew sergeant in “Fury.”

Brad Pitt gets to play to his relaxed, gravitas-oozing movie star strengths as tank crew sergeant in “Fury.”

Credit: Giles Keyte

‘Fury’

Director: David Ayer

Stars: Brad Pitt, Logan Lerman

Rating: R

4 (out of 5) Globes

Let’s get this out of the way: “Fury” is not “Inglourious Basterds,” nor does it try to be. It too features Brad Pitt killing Nazis (a word he pronounces right this time, though he prefers to just call them Germans), but that doesn’t mean they ought to be compared. John Wayne made scores of WWII pictures; one shouldn’t be forced to choose between “They Were Expendable” and “Sands of Iwo Jima.” Brad Pitt can gruesomely dispatch with Hitler enthusiasts as often as he’d like, and he might as well because he’s good at it.

That both are worlds apart helps too. “Basterds” was a jokey, hyperviolent what-if that rewrote history because that’s one thing movies can do. “Fury” invents history; the climax is based upon nothing but the feverish and problematic imagination of writer-director David Ayer, the author of “Training Day” and maker of “End of Watch.” But it’s grounded in reality; indeed, it grounds viewer’s faces in it, forcing them to stare at heads impaled or blown up, abdomens popped like watermelons, limbs snapped off by bulletfire that looks like lasers. (They’re even color-coded: the Germans get green, the Allies red. It’s just like “Star Wars.”)

More importantly he forces audiences to get up close and personal with the usual Ayer characters: ornery, hard-living, self-destructive, overtly jerkish, mega-macho, capital-M Men. After an eerily calm opening interrupted by Pitt’s Sergeant Collier (aka “Wardaddy”) leaping on and knifing a horseriding German soldier, “Fury” shows what it’s really about: hanging in the claustrophobic confines of a rusty tank with a bunch of a-holes. Collier and his nicknamed comrades — Mexican gunner “Gordo” (Michael Pena), redneck loose cannon “Coon-Ass” (Jon Bernthal) and steely but religious mumbler “Bible” (Shia LaBeouf) — bust each other’s balls at top volume, flinging casual racism at Gordo and making one wish to be anywhere else. If war is hell, so is this.

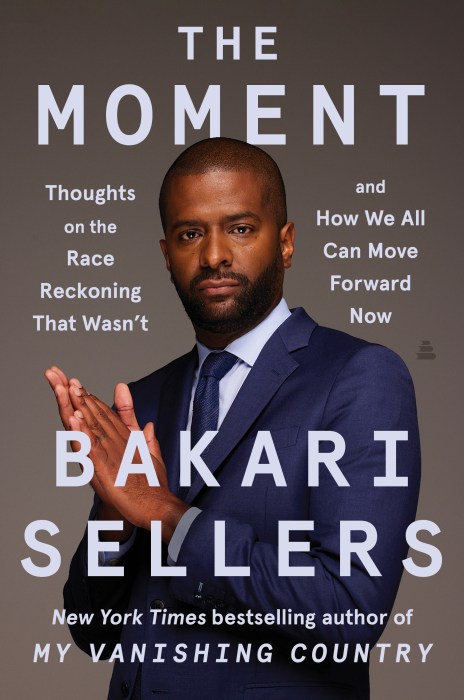

Logan Lerman (with Brad Pitt) plays an old war movie cliche: the fresh fish who gradually becomes tough.

Logan Lerman (with Brad Pitt) plays an old war movie cliche: the fresh fish who gradually becomes tough.

Credit: Giles Keyte

Ayer was last seen with “Sabotage,” an entire film stocked with these types, shouting inelegant profanities at each other and over top persistent gunfire. “Fury,” and its characters, luckily chill out. Even “Coon-Ass,” the most obnoxious, gets a token humanizing scene, while Pitt gives the kind of commanding, old school movie star turn where less is more. Pitt has always been a better comedic actor than a serious one, but now he can just stand there and ooze gravitas. We learn nothing about Collier, but staring at his face as he says nothing we can vividly imagine.

“Fury” also understands — better than any Ayer film has previously — that the characters’ machismo is all a front. These guys are all secretly crying on the inside, of course, but there’s something more. Their tough act is a way of not only mentally steeling themselves for living in war — and the film is set during the last days of the German front, when “total war” had been declared — but as a way of survival. They have to be inhuman, have to act scarier and more inhumane than anyone else, because that’s how they’ll be able to kill the other people who feel the same way. War, in “Fury,” is about how to become less human.

Though it subscribes to the the-more-violent-the-more-real ethos that drove “Saving Private Ryan” — and bandying about those three words no doubt scored it its $80 million budget — there’s no overarching plot, no real mission. As Collier says at one point, the mission is to go from town to town, ridding them of the baddies — an impossible-sounding feat, at least for one tank crew, that gives the film existential dread. It’s a series of episodes with no end in sight, though it slips in the tired cliche of the fresh fish transformed, or in this case corrupted. Needing a replacement second gunner, Collier’s team gets “Cobb,” a stammering scaredy cat played by today’s go-to stammering scaredy cat, Logan Lerman. Though he’s wide-eyed and petrified at first, it doesn’t take long for him to toughen up. When Collier forces him to gun down an unarmed German POW, his chickening out is so strong that he insists he’d rather die himself — that’s how messed-up the world of “Fury” is.

Shia LaBeouf (with Logan Lerman) doesn’t have a lot to do in “Fury,” but he fits right in. Perhaps he shouldn’t have fake-retired?

Shia LaBeouf (with Logan Lerman) doesn’t have a lot to do in “Fury,” but he fits right in. Perhaps he shouldn’t have fake-retired?

Credit: Giles Keyte

This scene is played as a form of hazing, complete with American soldiers egging him on and flinging homophobic epithets. Ayer loves to explore this world, but his films prior to “Fury” have all monotonous affairs driving home a single point. Turns out the characters were just misdirected. In war they have focus, but they also have depth. Ayer has always been an obvious Sam Peckinpah fan (he was even at one point working on a remake of “The Wild Bunch”). But with “Fury” he finally gets the mix of braun and quiet anguish. There aren’t many moments of emotion, except the ones between the five bros in a tank. (Gordo is introduced holding someone’s hand, which turns out to belong to the killed second gunner. The body had probably been there for awhile.) But the vision finally feels filled-in, the Peckinpah inspiration no longer an affectation.

Yes, “Fury” is another reminder that war is hell. But it’s one of the few reminders that war is addictive. Nearly every war film is ultimately comforting: Anti-war films tell us it’s inhumane; genre war films — the ones dads used to watch, even if (or especially if) they experienced the real thing — tell us that it’s heroic, even enjoyable. “Fury” has nothing good to say. Francois Truffaut, in a line deployed so often it’s become hackish to even mention it, said the problem with war movies is that they made war look like fun. For “Fury,” its best quality is that it does make it look…well, not fun, but exhilarating.

It’s not exhilarating for the audience, but for the characters. For the audience it’s deeply unpleasant: The gore is extreme horror movie-level gruesome — stronger than anything in “Inglourious Basterds,” and that had scalping — and the colors are shades of gray, black and crimson. It’s never fun to watch. (Though it is nice on the eyes, which is to say it doesn’t feature the unparsable handheld of “Sabotage” or the switch to bodycams in “End of Watch.”) But it understands why its characters get worked up in the midst of battle, why they gleefully shout names at the people they’re mowing down, why they high-five while committing unspeakable acts, why they cackle at taking out complete strangers who are perhaps fighting for the same superficial reason. Like “The Hurt Locker,” but in an even less explicit way, it says that to be good at war — or to even just to be in the midst of it — one has to imagine doing nothing else. It could be read as anti-war or even pro-war, and that’s what makes it unusually useful. It’s honest to the point of being uncomfortable.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge