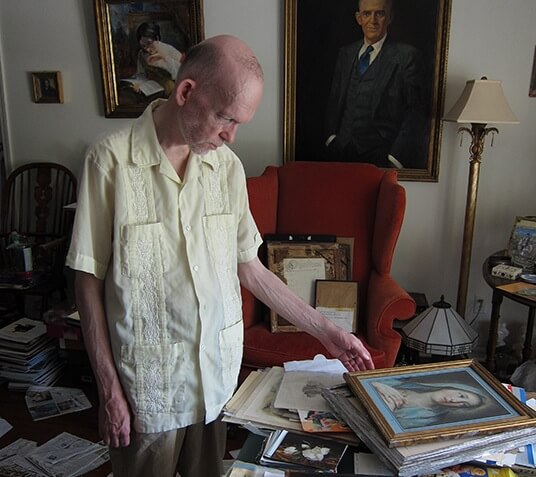

Mark Landis talks a lot. “I get distracted,” he admits while doing press for “Art and Craft,” a documentary about him. A response will segue into a discussion of how he became a Catholic (“To be honest, I’m not a proper Catholic”), or how Eleanor Roosevelt was among those who voiced concern that then-nascent TVs will rot brains. That he’s talking at all is frankly amazing. The reason he has a documentary all to himself is because of this: For over 30 years he was a serial art forger, who donated untold copies of paintings to museums all over the country. And we do mean “donated”: The reason he didn’t charge money is the only reason he’s not in jail. In fact, what he did is, thanks a loophole, not even illegal (which is not the same as being right). Amazingly, after seeing the film — for which he’s been traveling on the film festival circuit — few who approach him are ever mad at what he did. “I always get a good response,” Landis admits. “Everybody’s so gushy and nice to me, and heaped praise on me. It gives me a boost. In fact it gives me a swelled head. I really have to learn to practice humility.” Part of that may be his demeanor: He’s soft-spoken, with a high-pitched patter that barely breaks a room’s ambience. He’d seem meek, fragile, if he wasn’t also gabby and friendly, asking questions and — because he’s someone who uses TCM as permanent background attire — dotting his sentences with references to old movies (“The Ghoul Goes West,” with Robert Donat). You could never hate him even if you wanted to — one reason he may have been so successful at bequeathing museums ersatz wares. This also helps one see the plus side of what he does — that being a good art forger means being a good artist. One of the questions raised by the film is whether or not Landis is an artist. (His copies even wind up with their own gallery show.) Landis in the film proves modest, though one-on-one his answer to this is a little more nuanced. “Whenever I look at an artist bio they express this or that or have outrage about some sort of atrocity in the world,” he says. “I haven’t got any social concerns or spiritual concerns or emotional concerns or political concerns — any of that stuff I’d need to express through a painting. I just like to draw. I like pretty pictures.” He does defend what he did, to a point. “I enjoyed people treating me like a big, rich philanthropist. We’d all like to be treated like a king, wouldn’t we? Anybody can sympathize with that,” he charges. “If they hadn’t been so nice and treated me like a king for a day, I never would have done it again. I got addicted to it. Anyone can sympathize being treated like royalty. Besides, what did royalty every do to deserve being treated like royalty?” Still, all the buzz around the film seems to have replaced that. “I was just a lonely old guy, sitting around in my room, wondering what I was going to do now. And these two glamorous New York filmmakers showed up at my door and wanted to listen to me go on about my life story,” he says. “It was like an answer to my prayers.” He hasn’t donated for years, though he says it was more because of “gossip” making hard, not because it was the right thing to do. The film’s directors helped set up a website — marklandisoriginal.com — where people pictures for him to paint: of children, pets, themselves and things of sentimental value. “It’s a challenge because some of the pictures are difficult to work with. The compositions can be bad. I remember one of a mother and child where maybe a fifth of their face were cut off on the sides. I couldn’t see their ears. You can’t make a painting out of that. You want it to be presentable.” Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge

Interview: ‘Art and Craft’ subject Mark Landis on why he forged art for so long

Sam Cullman, Oscilloscope Laboratories