Filmmaker Michel Gondry’s latest, “Is the Man Who is Tall Happy?,” finds him chatting with Noam Chomsky.

Filmmaker Michel Gondry’s latest, “Is the Man Who is Tall Happy?,” finds him chatting with Noam Chomsky.

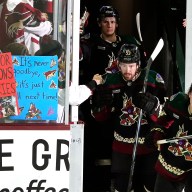

Credit: Getty Images

Michel Gondry has a reputation for whimsical works — but he likes a good challenge. From his many music videos with the likes of Bjork and the White Stripes to directing Charlie Kaufman scripts (namely “Human Nature” and “Eternal Sunshine of the Spotless Mind”), his work is by nature collaborative. With “Is the Man Who is Tall Happy?” — which he began in 2010 while directing the comic book movie “The Green Hornet” — Gondry takes long chats he did with philosopher and cognitive scientist Noam Chomsky and throws on animation that sometimes illustrates his points and sometimes remains purely abstract.

Throughout you confess that you’re nowhere near the intellectual league as Noam Chomsky. Why pick him to speak with you, and on film no less?

I always dreamt of making a film with a great scientist. I had the chance to meet with one who’s still alive. To me his scientific work gives credit to his political work. Many scientists are doing great scientific work, but if you ask them about politics they are very much vague. I got interested in Noam Chomsky through his political work. Then I got more into his linguistic work.

Art and science aren’t always perceived as bedfellows. What’s your own history with science?

I have a terrible memory, so it’s hard to accumulate data. But I love science. I didn’t understand it very much in school. I was artistically oriented from my earliest age, and when I tried to continue my [artistic] study, it was hard to find something that was not based in literature. I was not so much into literature. I was not so good at expressing myself with words. I thought the graphic arts were more my field. Art is more, in my opinion, connected to science.

This is a talky film, of course, but the animation is a reminder of how often filmmakers neglect the visual aspect of film.

Film was very visual until the talkies. Then it became more like theater. But at the very beginning it was a very complex form of art. It’s always about bringing back the visual art in movies. I know in terms of critics, you always offer an easier side to critique if you’re more visual. For them visuals are all surface — but for me, not at all. It’s more than surface.

How long did the animation aspect take?

It took me over three years, but I was doing other projects at the same time. It was my happy getaway. I would go back home and the setup was very simple: a lightbox with a camera attached with a lot of duct tape. I was drawing, taking a picture, drawing taking a picture. I would use a printer and do a little bit of work on Photoshop. I’d print out a picture then draw over it.

There are programs now where you can do hand-drawn animation digitally. Does that appeal to you?

With drawing on paper, there’s a level of sharpness. I could create a lot of texture. Then there’s the grain of the film. And when you shoot animation on film, between shots there’s this flicker effect. It’s not an effect I added digitally after. It’s not an affectation. It’s really coming from the technical approach. It gives the image this vibration that reminds me of old film.

You can’t really fake that stuff digitally, even now.

I think to fake it would be silly. It has to come from necessity. Maybe an audience would not see the difference. But for me it’s important that it’s not something I added after.

Each of your films is different from the next. Do you approach each like a challenge?

When you’re a director you don’t shoot every day. So every time you start again you have to readjust yourself to the medium. I’ve read interviews with other directors who feel the same. They’re new to their job each time. But there’s an advantage to that: You don’t get stuck in routines.

What about with your documentaries, including this? “Dave Chappelle’s Block Party,” for instance, was your first feature-length theatrical non-fiction film.

The idea [with documentaries] is it depends only on what happens during the shooting. I like this idea that you have to leave a space for things to happen live. I try to bring that to my fiction films. I remember shooting “Block Party.” It was super frightening to go out with a camera and shoot Dave Chappelle. Sometimes nothing would happen for one or two hours, or half the day. Then suddenly we’d meet the marching band, and everything would explode. It’s exciting but it’s the price you pay. And that was shot on film. You feel like you’re wasting film. It can be really boring — then all of a sudden it becomes exciting.