Reconsidering Mike Nichols’ bizarre ‘The Day of the Dolphin’

Provided

Mike Nichols died Thursday, aged 83, leaving behind a startlingly diverse body of work: He was not only a theater and film director but also a comic, and was a pioneer of all three. (He was also a really good actor, on the few chances he would bother; check out his sinister turn in the 1997 film of Wallace Shawn’s play “The Designated Mourner.”) Few film directors start off hitting the ground running the way Nichols did, with “Who’s Afraid of Virginia Woolf?” followed by “The Graduate.” His next two films are underrated: his ambitious, very funny and deeply, weirdly surreal attempt to pound “Catch-22” into a workable movie, then the bleak, despairing (and also often funny) “Carnal Knowledge.”

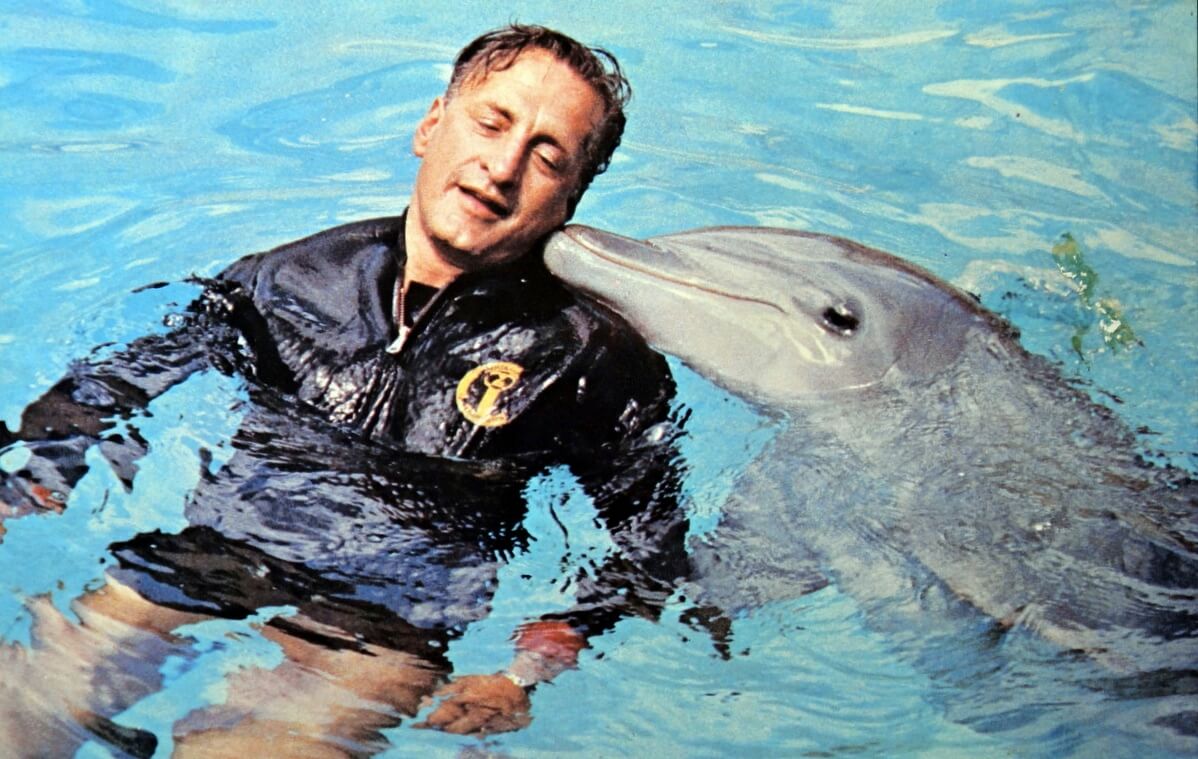

But what of “The Day of the Dolphin,” his fifth feature, from 1973? Its premise basically invites you to laugh at it. In fact, let’s just quote the peerlessly surreal tagline on the poster, a handsome drawing of a very grave George C. Scott in scuba gear with these words: “Unwittingly, he trained a dolphin to kill the president of the United States.” Unwittingly! What the poster doesn’t tell you is that the dolphin can also talk.

That this is played deadly serious — it’s a thoroughly ’70s Hollywood picture, which is to say bleak-o-rama — would seem to beg for audience snickers. Is it a secret lampoon of the era’s cinema — the kind of thing he and Elaine May would have sent up in their comedy days? No, and actually its sobriety is what makes it, perversely, work. In fact, the project was almost made by Roman Polanski, who abandoned it in the wake of the Manson murders. (Instead he made his magnificently dark “Macbeth.”)

It’s got smarts. Its inspiration was the growing science behind dolphin intelligence, which it mashed with the declining trust in government that swelled throughout the ’60s and exploded in the ’70s. Actually, the government isn’t the villain in “The Day of the Dolphin.” It was prescient to see corporations as the baddies, namely a shadowy foundation that is funding the dolphin research undertaken by Scott’s Dr. Terrell. Terrell and his staff work on a remote island, where they’re essentially vulnerable to outside forces. They’re slow to realize they’re being used by seditionists, training their two dolphins, Fa and Bea, to place a bomb on the president’s yacht.

It’s ridiculous and it’s not; it’s actually a pretty sharp plan, when you take it a little seriously. Nichols definitely takes it seriously. This is a handsome production, with cinematography from William A. Fraker (“Rosemary’s Baby”) and a score by Georges Delerue (of many Francois Truffaut films). It has the expected precise framing of Nichols films of the era. In the ’80s — after a shocking seven year absence, following the underperformance of the Nicholson-Beatty movie “The Fortune” — Nichols chilled out a bit, adopting a looser style. Here he’s still experimenting with editing (by Sam O’Steen) and the way his images were set up.

And the film’s really not that silly. Even the dolphin talk is passably realistic. Regular Nichols collaborator Buck Henry, who also wrote the screenplay, lends his voice to one of the dolphins, who just barely manages to squeeze out Pidgin English through his normal squeak-talk. It actually sounds pretty much what you’d imagine a talking dolphin to sound like. This isn’t a great film, but it does have a great ending — one of those grim ’70s conclusions that make you run for a stiff drink after. “The Day of the Dolphin” may flirt with stupidity, but it powers through anyway, as if it was the smartest film in the room. Naturally it underperformed, and has been exploited as an example of directorial hubris. It deserves to be re-evaluated, preferably by those not looking for a chance to snicker.

“The Day of the Dolphin” is available by Netflix DVD. It is not, alas, streaming.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge