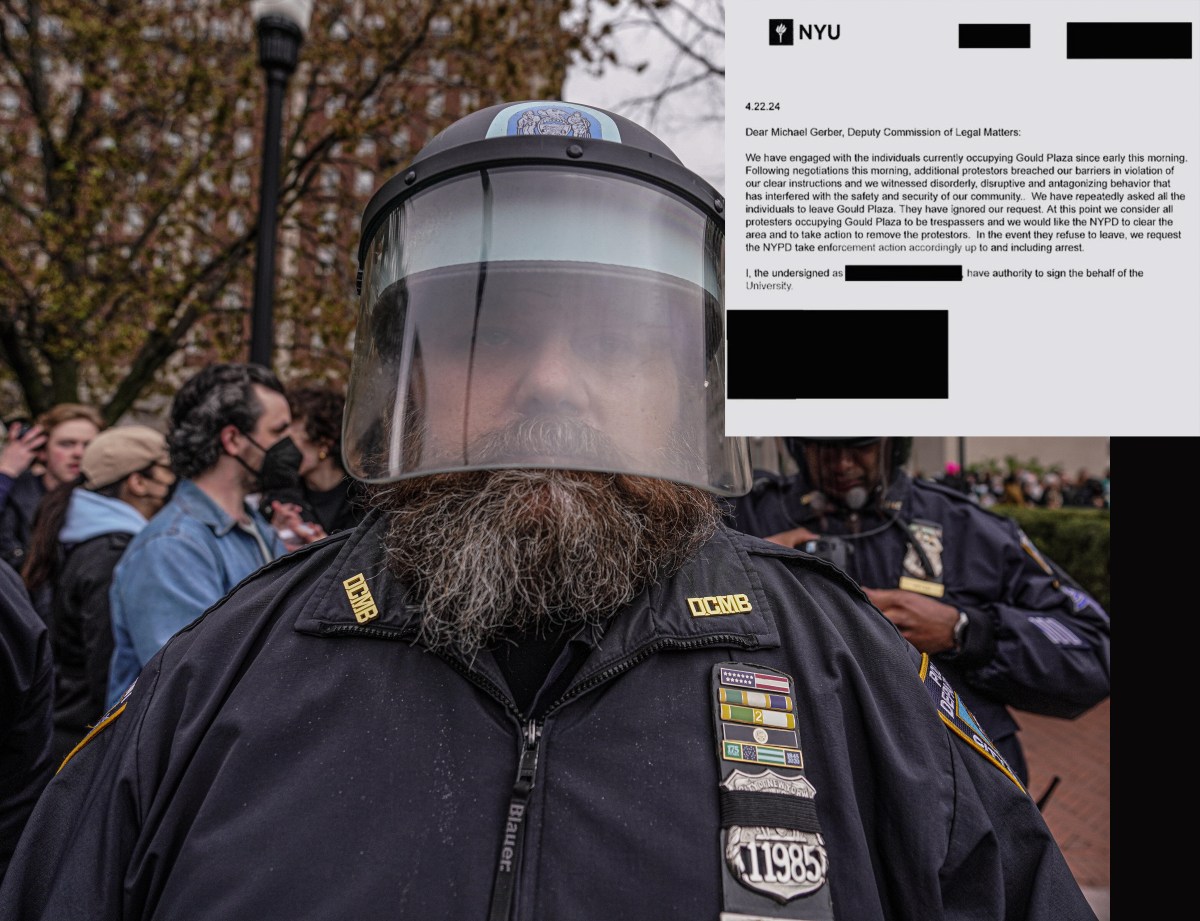

Imelda Staunton can’t resist Dominic West’s moves in “Pride.”

Imelda Staunton can’t resist Dominic West’s moves in “Pride.”

Credit: Nicola Dove

‘Pride’

Director: Matthew Warchus

Stars: Ben Schnetzer, Imelda Staunton

Rating: R

3 (out of 5) Globes

In the ‘90s, indie cinema teemed with gay rights dramas: tales of coming out, of battling homophobia, of being LGBT both then and in the even less enjoyable past. Some of them were good, many were terrible, and almost all were painfully earnest. But they performed a noble service, quietly (or not) influencing the culture, helping to pave the way for the quasi-tolerance with which we live today. Having done their job, they then, for the most part, slipped away, replaced with films that treat homosexuality with the casualness the subject deserves.

In that respect, the arrival, right now, in 2014, of “Pride” — a real-life tale about gay rights activists trying to convince a South Wales town to let them help with a miners’ strike in 1984 — can’t help but feel like a throwback. It’s not that homophobia is dead, though “Pride” doesn’t make many overt connections to our present. It’s a double nostalgia piece, reminiscing about both a time when gay rights activists were really up against it and when films exactly like “Pride” flooded art house theaters.

Perhaps in 1995, “Pride” wouldn’t have seemed so special. Indeed it’s (sorry) proud of the many, many cliches it offers. It begins with the token shy kid, Joe (George MacKay), who hides his leanings from his button-up parents. Slipping off to a gay pride parade, he happens upon a motley crew, made of other cliches: Mark Ashton (Ben Schnetzer), the tough but vulnerable guy, out and vocally proud; and Jonathan Blake (Dominic West), the older guard, who in this case is the second man in the U.K. to be diagnosed HIV positive. (Both Ashton and Blake are based on real people. Blake, amazingly, is still very much alive and kicking. Ashton, sadly, is not.)

Ashton is bored with the scant progress his group has made. He proposes they up the ante by joining up with another, at the time even more hated group: the nation’s miners, currently engaged in a very unpopular strike. At random they chose an aggressively remote mining town, and after raising enough money they decide it’s a good idea to drive up there and meet these blue collar, 1980s types — many of whom have rarely wandered past the tight confines of their home — in the flesh.

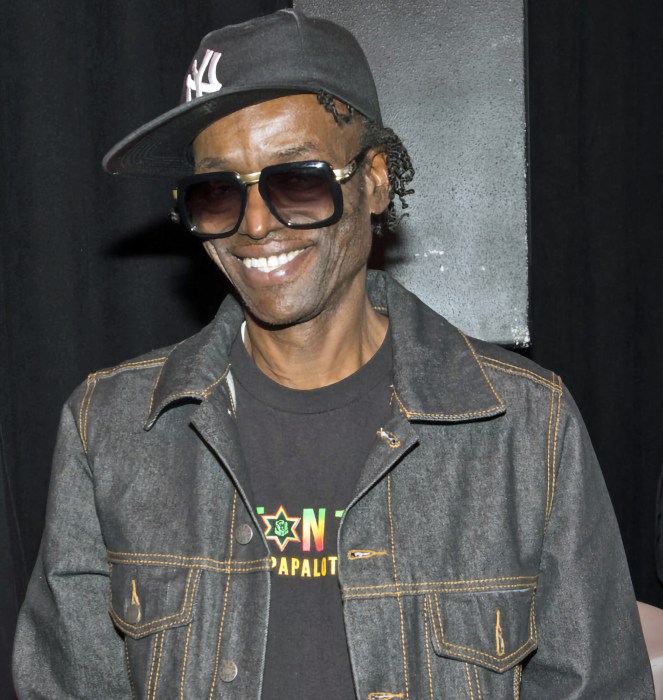

“Pride” details the unlikely partnership between gay rights activists and striking minders.

“Pride” details the unlikely partnership between gay rights activists and striking minders.

Credit: Nicola Dove

Much of “Pride” is about regurgitating cliches from a bygone era of cinema. Two decades removed they no longer seem irksome. Now they’re comfort food, or like old friends you once grew tired of but find charming after such a long absence. But “Pride” doesn’t use all of them; it picks and chooses which cliches to deploy. For instance, the film isn’t really about a backwards town learning to like gay people. The miners, even the ones the activists personally rescue from jail or other calamities, are reluctant to even shake their hands, and they don’t get much warmer even after they do.

Instead it focuses mostly on the ones who do like them. Chief among those are the women — including Imelda Staunton — who not only embrace their flamboyantly out guests but giddily, cacklingly embrace them. Much screentime is burned with scenes of giggling older ladies on the equivalent sugar highs, doting over their new friends, begging to go to gay S&M clubs and elated when accidentally finding their hidden dildos. The novelty of these scenes might have grown old if there wasn’t something genuinely touching to them. The women aren’t just being tickled by new experiences but tapping into old ones — the days when they were slimmer, sexier and perhaps thought they might do more than live in a cloistered, homogenous small town.

“Pride” gets so hooked on scenes of activists hanging with their mining town friends — which also include Paddy Considine, as the soft-spoken head of the strike team, and Bill Nighy, as an eternal single man with a pretty obvious secret — that it actually forgets to be a lesson in tolerance. That might be perversely refreshing for a gay pride movie, but it also means the film doesn’t properly convey the makeup of the town, or detail how they came to at least somewhat appreciate the hard work of their unlikely saviors. There are only a couple of haters, namely a miserable crone and her hotheaded sons, and the film perhaps wisely never pretends to redeem them.

But that’s what really distinguishes “Pride” from its forefather films: It’s not about tolerance but about the fight. Like its characters, it lacks self-pity, as it’s too caught up in revolution and enacting real change. Its heroes know they sometimes have to play dirty to get results, just as the filmmakers know they have to tug at heartstrings and play cliches to get people caught up in the action. But ultimately it takes for granted that the audience is already on their side and doesn’t need further convincing to care for what’s onscreen, and that’s what really makes “Pride” a gay pride film for 2014.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge