Robert McKee comes to NYC in April. To learn more or purchase tickets, visit www.mckeestory.wordpress.com.

Robert McKee comes to NYC in April. To learn more or purchase tickets, visit www.mckeestory.wordpress.com.

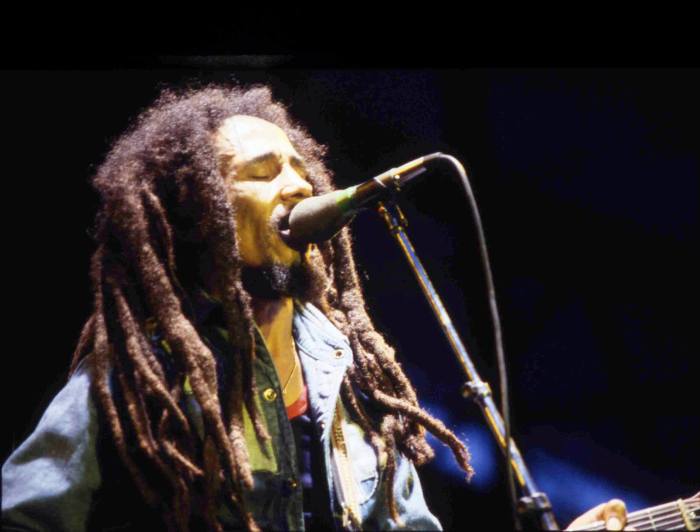

Credit: Facebook

When it comes to prolific storytelling — from blockbuster screenplays to best-selling novels — credit may not necessarily be due entirely to the man behind the pen. It may have a lot to do with the man behind the podium. Robert McKee has been teaching writers their craft for more than 30 years. His students comprise names you will assuredly recognize, including 12 of this year’s Academy Award nominees. McKee’s world-renowned seminars are now coming to New York City, starting with his famous four-day summit on STORY (April 3-6) and followed by his GENRE series (April 9-13).

We asked the influential public speaker to give us a little taste of what’s to come, with a sneak peek of some of his best writing advice, below:

In addition to being a dedicated lifelong teacher, do you consider yourself an ongoing student of the craft? Has your philosophy changed with time?

Yes, periodically something I see causes me to rethink and sometimes gives me a whole new insight to ideas I haven’t had before. A few years back the climax of “The Sopranos” caused a lot of controversy. And I thought about it and studied it a bit. And I came up with an idea I never had before in my life, which is that there is an editing that I never considered —that especially for a long-form works, like a television series, when you exhaust all the dimensions of a character you come up with an ending that is somehow satisfying. … Everything you can express about the characters has already been expressed, there’s nothing left to do, and you don’t need to come up with a climax. It’s just a sense of completion, or the character emptied out totally. And that can be satisfying in a quiet kind of way. So every now and then something like that comes along that makes me add to my understanding.

Can anyone be a good writer or do they have to already be talented?

Yeah, they have to have talent. [Laughs] No amount of study and perseverance and dedication and hard work will ever make up for the fact that somebody has no talent. That’s a genetic gift. We call it a gift because you literally get it from your parents or grandparents — there’s somebody that gave you that gene. It gives you the right brainpower to discover that hidden connection between things that already exist, but a connection no one else has ever seen before. In a nutshell, that’s talent. … You either have it or you don’t. And the notion that anybody can write a screenplay or anybody can write a novel —no.

Don’t a lot of people think they have talent when they don’t?

You’d be astounded at the number of those people. [Laughs] Here’s what happens: There’s a lot of bad writing in the world. The vast majority is mediocre at best, and the huge percentage of it is just perfect crap, and it still gets made and published. So we suffer through a tremendous amount of bad writing. People without talent look at this bad writing and think, “I can write as well as that! And if that mediocrity and banality gets made and published, why shouldn’t my mediocrity and banality get made and published?” … And so years go by and they write stuff that’s, you know, ordinary, and then they feel that there’s a great injustice in the world if they don’t get produced and published. There’s nothing I —or anyone — can do to help those people. You can’t teach talent. I can teach them craft and skills.

I do my very best when I’m lecturing to try to drive the dilettantes out of the room to save these people of years and years of frustration. And I point out to them how hard it all is and that it’s gonna take them 10 years: Ten novels or plays that no one will want to publish. They have to be willing to put in 10 years of failure and to produce one major work a year, and maybe more, and fail. When I point that out, that the finest of writers labored for dozens of years and produced dozens of [unpublished works], it has the effect that I want it to have, which is to discourage the weak.

If a writer does have the intelligence and the talent, what advice do you give them so they can get past their own egos and insecurities?

They can learn how to read their own writing in an objective way and not mistake their intention for results. So I try to teach them how to separate what they think they wanted to write, what they think they did write and what they actually wrote. The second thing they can do is they can just give it to people, or pitch it to people, and just look in their eyes. Sit people down, don’t make them read you; just tell them your story from the beginning to the end. Watch their eyes and see where they lose interest, see if you’re holding them and moving them. If you can’t hold the interest of an intelligent, sensitive person in 10 minutes, how are you going to do it in 120 minutes on the screen? … The difference between amateurs and professionals: Amateurs just love everything they write; they have filing cabinets of the stuff. Professionals hate everything they write. They’re destroying their work in pursuit of excellence because they have high standards and they are holding themselves against the finest of writing.

You have to be able to be ruthless to your own writing. Then you pitch it to people and see how they react. Between the two of them, you can figure out whether or not you have something worth trying to perfect.

Is there a way to know when the story is done?

One of the components of talent is taste. Some people have it, and most people don’t. Writers know when they’re done when they’re able to read what they’ve written and recognize that it’s good writing. The second thing that tells you when you’re done is when you do try to rewrite it, it gets worse, and then you realize you’re taking it backward. Then you have reached the pinnacle, you should stop. Really fine writing creates a surface of language beneath which there’s huge reservoirs —and when those reservoirs start to dry up, when characters are starting to explain their thoughts and feelings in the dialogue, when you’re making it shallow by putting it all on the surface, now you realize you’re going backwards, so you should go back to the previous draft.

When you put it in the hands of a producer or publishing house, how much does the writer let it go?

You just don’t give it to them without knowing in advance how much of your vision they share. If it’s really good writing, you will have an agent. And the agent will put it out to various people, and if it’s superior writing you’ll have a choice of who will publish it. So before you sign anything, you sit down with the people and ask them to tell you your story without any notes in front of them. Because the story you’ll hear them tell is the story you’ll end up with. And if it doesn’t sound like the story you wrote, get the hell out of the room.

If the story they tell you sounds like the story you wrote, [ask]: “What are your favorite novels, what are your favorite films, what are your favorite plays?” What they name now is what your work is going to look like. If you’ve written a drama and their favorite works are all comedies, again: Get out of the room. They understand the story, but they don’t understand your tone. Before you commit to production, you make certain that they understand what you’ve written.

People say that there’s nothing new in Hollywood. Do you think there are still original stories?

Absolutely. And the future is breathtakingly positive. I am extremely enthusiastic and excited about the possibilities of long-form writing. The best writing today, without a doubt, is on television. The writers offer a whole new level of complexity that the world has never seen before. The longest novel ever written is a season, at best, of a great series. From “Breaking Bad” to “True Detective” and “Mad Men” and “Curb Your Enthusiasm” — these great series have a level of complexity in character and relationship that no writing in history has approached.

When someone attends your seminars, what are they most often surprised by?

They’re going to be surprised that they have a greater knowledge than they know. They’re going to be surprised that they “get” this — [but] there’s an aspect of this great art that’s run right over their head. There are gaps in their knowledge that they need to reclaim. It confirms them on one hand, but there’s a lot of undone work they have to do in the future if they want to understand their profession.