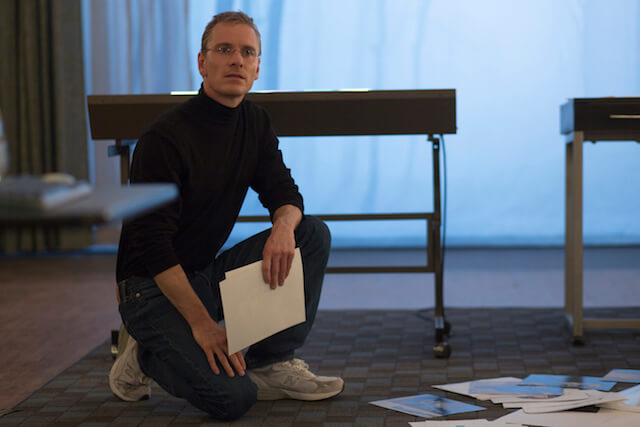

‘Steve Jobs’ The Aaron Sorkin-built “Steve Jobs” only has three “scenes,” but there’s a mountain of sheer stuff crammed into them. Each section, charting the real-time-ish build-up to three of the tech god’s key product launches, is endlessly wordy, endlessly busy, with roughly 10,000 moving parts, not the least being characters scampering between rooms and not-yet-filled auditoriums as they breathlessly volley fine Sorkinese. The segments are so dense, so teeming with quips and heady thoughts, that it’s almost a shame to try to suss out big ideas. That would simply seem reductive — an attempt to tame a film that’s at its best when it’s simply moving. RELATED: NYFF reviews: Steven Spielberg’s “Bridge of Spies” and Michael Moore’s “Where to Invade Next” Reducing it to big ideas is exactly what happens in “Steve Jobs” — eventually. It’s two great, breakneck episodes followed by a third that fumbles when it tries to tie it all together, and especially when it tries to make us feel for Michael Fassbender’s perpetually wigged-out Jobs. But it mostly avoids being the film it shouldn’t be. It’s not a simplistic missive on What Steve Jobs Means or Who Steve Jobs Really Was or How We Live Now. It has plenty to say about all three, but it buries them in tune-out-and-miss nuggets dropped into dialogue or made subliminally. “Just because you say so doesn’t make it so,” someone scolds at him, in a wink-wink-nudge-nudge lines. But his dream is to make saying so being so. It’s a stray line that fills one piece of the puzzle, encouraging one to think of its prickly anti-hero trying to shape the world as he semi-sociopathically lives it: as emotionally cold and disconnected from people, trying to micro-manage how he’s seen publicly while he misbehaves behind the scenes. And “Steve Jobs” stays entirely behind the scenes. It’s even a kind of backstage musical — a Busby Berkeley movie that cuts out right before the eye-popping numbers, in this case the product launches themselves. (With its surfeit of long takes speed-walking and talking, it also smacks of a “Birdman” but with cuts.) At heart it’s a simple rise-and-fall-then-fall-some-more-then-rise-like-Olympus narrative. The products are the semi-successful original Macintosh in 1984, the failed, box-shaped NeXT computer in 1988 and the comeback triumph that was the iMac in 1998. This doesn’t remotely tell the entire Jobs story, like “Jobs” or the recent doc “Steve Jobs: The Man in the Machine,” but it gets a lot in, and it has a shape, a perspective. Its perspective is that Jobs was, to put it simply, not very nice — not that that’s a bad thing. One of his first lines is “F— you,” and to meek, sweaty troubleshooting guru Andy Hertzfeld (Michael Stuhlbarg) yet. He’ll proceed to demand too much of his trusty right-hand-woman Joanna Hoffman (Kate Winslet, with light/sketchy Polish accent), who does everything from actualize his more impossible whims to speed-iron shirts. And he’ll play remote and testy to those he’s screwed over, from Seth Rogen’s firm but ever-giggling Steve Wozniak to Jeff Daniels’ jilted/jilting father figure John Sculley to an ex, Chrisann Brennan (Katherine Waterston), who can’t believe Jobs won’t claim parenthood of Lisa, the little girl they sired. Jobs’ relationship with his daughter (played by three different girls) is eventually meant to be the film’s emotional fulcrum, with our protagonist going from frigid to misty-eyed, and therefore likeable(ish). For what it’s worth it’s unclear if we’re even supposed to buy this about-face as on-the-level. There’s a suspicion that Sorkin’s structure is mirroring the way Jobs knew how to manipulate people, enacting long cons to snooker those he’s abused into at least adopting an “it’s complicated” position on him, as the real Wozniak and Hertzfeld hold. The final five minutes is a Hail Mary for our feels — an embarrassment of empowering music, flashing lights and halo-heavy shots of Jobs himself. But it might also be a joke — a sarcastic salvation for a monster who wanted to trick the word into thinking like him, and to a degree succeeded. RELATED: Michael Moore on gun control and what he likes about America That might be an overly generous reading, but it would be more in line with what precedes it, which is efficient and crafty and more like a machine that only knows how to go. Danny Boyle, more ringleader than visionary, gives it a feeling of controlled chaos. At first he simply does what all others have done with Sorkin-speak, which is filming in long takes. Soon he gradually opens the film up, which is to say he starts adding more traditional Boyle-esque flourishes: expressionistic lighting, lots of cutaways and showy canted angles. Even the texture of the film quietly changes from segment to segment, starting off in Super 16, then 35mm then overly-clear (and tricked-out) digital. A film about movement, it too evolves. Sorkin’s script changes tone too. In the final third the confrontations that have seemed brief and, by Jobs, reluctantly engaged — mostly between Wozniak, Sculley and Brennan — get super-sized, even maudlin. The Sorkin talk, prone to hilarious pissiness even over nice things (when someone casually notes Lisa is growing, Jobs offers a sarcastic “They get taller!”), makes way for the vomit-worthy. The nadir isn’t, miraculously, Wozniak ending a righteous tirade by crowing that life “is not binary; you can be decent and gifted at the same time.” It’s Jobs, in the finally moments, actually saying, “I’m poorly made.” (Just like a gizmo!) These are hoary mis-steps, though, in a film that otherwise trusts that we’ll find significance wherever we can. It’s more a Rorschach test than a film telling us what to think. And it understands this more than anything: that there are few pleasures quite like the sounds and sights of smart assholes talking. As ever, not only does Sorkin understand what makes cruel geniuses tick; he even likes them.

Director: Danny Boyle

Stars: Michael Fassbender, Kate Winslet

Rating: R

4 (out of 5) Globes

‘Steve Jobs’ isn’t a simplistic look at the Apple god (till the end)

Francois Duhamel

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge