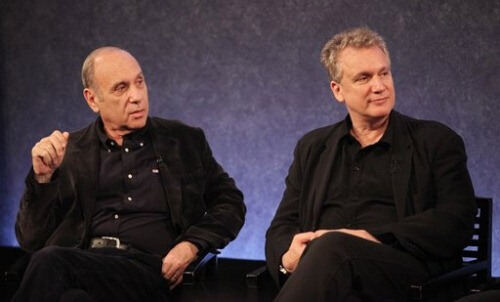

On a particularly sunny day in January, we were graciously invited to the NYC home of Rick Elice to meet with him and Marshall Brickman about the process of co-writing the book of “Jersey Boys.”

So how did this collaboration get started?

Elice: A friend of mine had the rights to the catalog of Four Seasons songs, and [he] said, “How would you like to write a musical about Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons?” … I said, “You mean the guy with the really high voice?” He started rattling off these songs titles, all of which I knew, but never associating them with the same group. And he sent me a compilation CD set of all their stuff. I said, “Marshall Brickman and I’ve been looking to write something.” … Not only had we not worked together, but neither of us had ever written a Broadway musical. So I said, “Send me the songs, I’ll go over to Marshall and we’ll see what can happen.”

And I went over to Marshall’s apartment, and we went over the songs. And the early songs, the real bubblegum songs, the first flush of their success, are really similar. Over the course of the life of the group, the music begins to change [and] the arrangements become more sophisticated. There’s a style that is separate from other groups of the time. “The Four Seasons” and “The Beach Boys” were the only two American groups that survived The British Invasion in the ‘60s. And then there was one of their big hits, but it was a Frankie Valli solo song, “Can’t Take My Eyes Off You.”

We had no idea that was him.

Elice: Right? And the song itself is … not a pop song. And in 1967, it really didn’t sound like anything else. And we both– Marshall, of course, is a great screenwriter, and I’m a film fan – in 1979, remember being very affected by a film that came out that year, “The Deer Hunter.” Because I was in a play with Christopher Walken at exactly the same time, so I went to see this movie a lot. I remember very vividly a scene in that film where this song was featured. And so did Marshall. And that was, I think, the first kernel of an idea that there would be something to write about, other than just a chronology.

The fans of their music looked very much like the guys who were in the band. They were blue-collar guys – guys, first of all; not girls, primarily – like the guys in the group. And in “The Deer Hunter,” they’re all about to ship off to Vietnam, and the night before they leave, they’re in the local bar, a steelworker tavern in Pennsylvania, and this song comes on the radio and they stop playing pool and they stop drinking, and all of these guys start singing this song, and they know every word, and they all know the horn introduction to the chorus. And it’s all kind of powerful, music as a socializing event in our lives. And that sort of hooked us in. And then we got to meet Bob [Gaudio] and Frankie– which of course we did in the back of this dark restaurant on W. 46th Street. And we asked, innocently enough, for them to describe, while we waited for the food to come, what it was like to grow up being them.

And they told us, sort of in a thumbnail way, their story. You know in a movie it says, “based on a true story”? Not only was this a true story, it was a good story. We were leaning forward the way people do when they see the show. And it was an untold story. At the time, when they were putting records out, if it were known that these guys had prison records and that they were locked up, their stuff never would have gotten played. As writers, we reacted instantly. We had accidentally stepped on the mother lode.

Were they concerned about revealing that, knowing you were interested in writing about them?

Elice: In theory, they weren’t. They rather courageously said: “Take a shot and do something warts and all, and we’ll decide when you go too far. And if lives are gonna be in danger because of what you’re doing, we will pull you back.” In good faith, we wrote something on spec, which they saw and liked, and they gave us the gig. And we found the producer. Through the producer we got Des McAnuff to direct it. And very quickly we got the slot in La Jolla. And we wrote the show in earnest in the late fall of ’03, and we started rehearsals in the summer of ’04.

And when did it all begin?

Elice: Maybe a year before that, was when we were thinking about it. But we didn’t start working on it in earnest until Des was on board and we knew that had a slot. He said, “If you can write it, we’ll do it.” We had, what they call in Hollywood, the ticking clock. That was a date, in the summer of ’04, when we had to begin.

So it sounds like you mainly worked with Frankie and Bob?

Brickman: We didn’t work with them. We did a lot of research about the group, which included interviews with them. But there was a lot of stuff out there. So it wasn’t a question of us all meeting and writing the script. They actually, quite intelligently, kind of stepped back. Because they realized that they lacked objectivity. The only thing that they retained was the right to kill the whole project if they didn’t like it. After we interviewed them and did all our research and wrote it and put it up at La Jolla, then they came down and looked at it. So it was interesting, a big gamble, a big roll of the dice for us.

There were no points of contention over it?

Brickman: When you’re dealing with living people, and with relationships that extend out into the community, there are things that might be more interesting dramatically but which are perhaps a little less palatable so those people – that is to say, ex-wives and ex-girlfriends, that sort of thing. So there was a bit of negotiation going on. We had to change some things at the request of Bob and Frankie – which we happily did; and in fact, I think it made it better. Everybody has an ego, and everybody has an ex-wife.

Elice: And you know, it’s their life. In theory, it’s one thing to say go ahead and put it up there, but when you actually see it … they have said to us [that] it’s a little surreal watching yourself.

It was never the director’s intention, or ours, that these would be impersonations. They’re fully fleshed-out performances. … They’re doing their versions of those guys as human beings. The songs that they sing are obviously the songs that the Seasons created and recorded and are famous for. The [group decided] that the falsetto would have the lead. Now that’s kind of old news, but it was big news back when “Sherry” came out. … No one knew what the hell was going on, because they weren’t written about. … They didn’t have long hair, they didn’t have exotic accents, there was no glamour quotient. You were never able to pick up a magazine and read something about “The Four Seasons.” They didn’t come from across the pond, they came from the wrong side of the river. … Now, the show is sort of edifying for them and for guys like them.

Do you take umbrage with the term “jukebox musical”?

Brickman: He has a whole rant about that.

Elice: This term was sort of hatched as a pejorative.

Brickman: The category is no use to anybody unless someone is looking for a felicitous phrase that contains a little bit of criticism, a little bit of condescension. And it’s very far from anything other than – you know, a description of something that’s existed for 75 years.

Elice: To some degrees, it became out of style to trash jukebox musical, because suddenly it was what people liked. So then it became, “It’s bad when things are adapted from films.” But as part of our modern way of communication, theater has always been about adaptation. Shakespeare adapted the story of two lovers in Italy, and it became “Romeo and Juliet.” … For hundreds of years, people have been saying there are no new ideas. It’s just about how you’re going to tell it. … It’s a kind of classification. … But then “Spring Awakening” opens and nobody writes about how it’s an adaptation of a play from 1903 – because they liked it. … And that’s what we, as writers, hope to do every time: make people forget their prejudices, their lives, what happened in their day – to be transported alongside thousands of other people in the dark. It’s about having fun, it’s not about category.

Brickman: Nothing in life is a documentary. Anytime you exercise editorial discretion, it’s not truth anymore. It’s something else. … This is going to sound facetious, but there is a higher truth than exactly what happened. … [“Jersey Boys” is] biographical, and it’s accurate.

So what’s up next for you guys?

Elice: We’re working on a couple of new plays, and we’re working on a film together about some people Marshall knew when he was earning his living as a musician [about The Mamas & the Papas]. And Marshall’s got another film coming out, and I’ve got a play that’s going to be on Broadway this spring [“Peter and the Starcatcher”], and life is good.

Brickman: I have a film that I wrote a while ago: a small, kind of independent film that’s close to my heart that I’m going to try to get out this year — with any luck. But it’s very hard to get a film out that doesn’t have anybody dying — nobody dies in this film.

And for “Jersey Boys”?

Brickman: “Jersey Boys,” we could not kill it with a stick. It’s the gift that keeps on giving. We’re going to be in places I’ve never been to, some that I’ve never heard of: South Africa, the Pacific Rim.

Elice: They’ve been playing Philadelphia for two months [on the second U.S. tour], and they’re breaking the house records that they broke last year. … It’s been playing two and a half years in Australia, and it will tour another year and a half around the Australian continent. But before the tour begins, we’re going to play for four months or so in Auckland, New Zealand.

I went there for a day in November to talk to people about the show. And you think … how would they even know about Frankie Valli and The Four Seasons? [But] Frankie’s going to play for two weeks, that’s how excited they are. And there’s only a couple million people in the whole country of New Zealand, it’s not like New York City or the United States. They’re so juiced about the show there, it’s kind of remarkable. He’s going to be a national hero. He doesn’t like to take long plane trips anymore, so [you can tell] he’s very excited because he’s taking a very long plane trip.