Tilda Swinton plays a 5,000-year-old vampire in Jim Jarmusch’s “Only Lovers Left Alive.”

Tilda Swinton plays a 5,000-year-old vampire in Jim Jarmusch’s “Only Lovers Left Alive.”

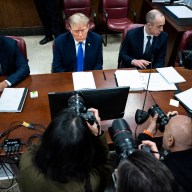

Credit: Getty Images

Tilda Swinton and I talk cough drops first. She has slight throat issues, and upon discovering that I do too, she shares from a rather large booty of cough drop bags she’s been given by the publicist. She winds up giving me one of the bags to take home. This kindness doesn’t seem out of character for her; Tilda Swinton may ooze rock star magnetism, but she’s approachable and almost bewilderingly friendly. She’s gabby and animated, even despite claiming that she’s reeling a touch from being underslept. After comparing and contrasting cough drops — one is “much too sugary,” she says, and we “should junk it” — we chat about the importance of sleep, which leads to a larger discussion of death.

That’s a perfect segue into her new movie, “Only Lovers Left Alive,” an oddball vampire number she’s been concocting, off-and-on, with the filmmaker Jim Jarmusch. Swinton likes to develop relationships with filmmakers. It’s how she started off her career, in the 1980s, when the late New Queer Cinema legend Derek Jarman coaxed her into the medium. This is her third Jarmusch, after bits parts in “Broken Flowers” and “The Limits of Control,” and the first in which she’s a co-lead. She and Tom Hiddleston play Eve and Adam, centuries-old lovers who function so well that, at film’s start, they’re apart: she in Tangier, he in Detroit. They spend their time together mostly listening to records, talking, making out and eventually trying to figure out what to do with Eve’s troublemaking sister (Mia Wasikowska), who has showed up and popped their bubble.

Among other things, this is a great film about death.

This is a film about immortality that we were preparing for eight years. The week after we started shooting, my mother was diagnosed with terminal cancer. She was on the fast-track out. And so suddenly this film became, for me, about dying. I look at it now, and that’s what it is: It’s about how you prepare to die. One thing I find interesting is Adam — he’s laboring under immortality. He wants a way out. He wants to go. It’s too much for him. And she manages to retain her perspective, not by just surviving, but by being so wired into nature. Nature is constantly dying and being renewed. She’s able to have that perspective because she totally accepts death.

I think that anything, any piece of work that’s about immortality is essentially about mortality. Any discussion about immortality will be about how we’re all in a cul-de-sac. It’s coming for us all. It’s even coming for them, sooner or later. The stars are coming down, eventually. Even in another 2,000 years, it will all end. In a way he doesn’t really know that, and that’s why he wants to shoot himself in the heart with a wooden bullet. But she really does, which is why she’s so relaxed. So I would suggest that the more one accepts that it’s on its way, the more relaxed one can be and forget about it.

There’s a quote you have where you said every movie should take 11 years to make.

This was only eight. It’s actually true: When developing work, I love the long gestation period. It does have its tough moments, when you wonder if you’re ever going to do it. I have a very great track record of — I’m trying to think if I’ve been involved in a longstanding project that hasn’t actually happened. So far, really, almost not. There are a couple things, but I still believe they’re going to happen. That means I’m pretty relaxed in that long gestation period because I know, when that money finally comes through, we’re going to have to run. Whatever it is you think you should have been doing, it just takes time. There’s always someone who comes in at the last minute who you can be grateful for, or some location that only becomes available at the last minute. The greatest challenge is, like in this film, fatigue — and lack of confidence, moments of thinking, “Actually, is this worth doing?” But if you can keep rebooting your interest in it, you’ll get there in the end.

What was the project like when Jarmusch originally pitched it to you eight years ago?

He rang me up on New Year’s Eve, and he basically said, “Hey, man, let’s do a vampire film about two lovers.” It just felt like a natural evolution for him, and I was thrilled. One of the first things he did was he gave me the Mark Twain diaries of Adam and Eve [“Extracts from Adam’s Diary” and “Eve’s Diary”], which is a beautiful, very playful set of diaries of the original Adam and Even in the garden of Eden. Adam, grumpy, stomps around the garden, noticing this very flighty, positive, annoying person he calls “It.” That was the model of the relationship, the fact that they’re so different. Her relationship is with nature, and naming everything and being so positive. And he, who is grumbling about her constantly, ends up putting a gravestone on her grave, which says something like, “Heaven was wherever she was.” Underneath every punk curmudgeon is a romantic.

It’s also a great relationship movie. It’s a positive look at a long-term relationship, albeit not one that’s 100 percent optimistic and flowery.

That was a very important part of it for us. We wanted to show a long relationship between people who were really communicative with each other and really, really into each other. They’re good for each other, so when one of them gets down the other one can really help. That just feels real, and it feels unexplored. We’re always seeing relationships start or we see them end. But we rarely see them just play out. They dig each other, even though they’re so different. That was another thing: to show a relationship between two people who are so different. We’re so used to seeing people changing themselves for each other. They’re chalk and cheese. They’re yin and yang, and yet they really like each other.

Still, when they’re together they change, at least temporarily. He gets less brooding and she comes down a bit closer to his level.

They bear witness to each other. They live in their own soil. They’re planted in different places and yet they support each other. They may be away for a year, but in their time scale that’s probably like a weekend. It’s not exactly a long-distance relationship. They also have Skype.

He’s very worried about the world, and yet both of them live in these bubbles, divorced from the rest of world.

By their very virtue of the fact that they’re so long-lived, and the fact that they are vampires, they are out with human society. They are underground. They are in the wainscoting. They need to be outside of human society, but they both have different ways of doing it. He does it because he’s so young, and maybe because he’s an artist, he’s still enough aware of the ins and outs of human society to be annoyed by it and alienated by it and angry with it. She’s just so long in the tooth. She’s got this perspective — as she says, “We’ve seen it all before.” Or at least she has. She’s been through the Inquisition, all Holocausts. She’s not sweating the small, medium or the big stuff. She’s just surfing the wave. She’s a survivor. Which is why she wins at chess. She’s just got that long game down.

But even though she is out with human society, she retains a compassion for humans. I think she likes people, which is why she lives in Tangier instead of Detroit. He’s so defensive about humans. He’s the rock star and he doesn’t want to be bothered. He’s too egotistical. She’s beyond ego. But who knows whether in another two-and-a-half thousand years, maybe he’ll change. Maybe it’s just age and perspective. But I also suggest, maybe by the very virtue that he’s an artist and his work comes from inside him — maybe it’s how he’s wired, and he’ll always be like that. He needs to be a little alienated and upset. But then he’s all right, because as she says, he’s been very lucky in love. He’s got her. He doesn’t have to be by himself, because he has her to pick up the pieces.

You’re on the faculty of filmmaker Bela Tarr’s film school in Sarajevo. He’s sworn he’s retired.

He says he’s never going to make another film. And I know he means that. But never say never, I don’t think. I’m hoping that making The Film Factory, which is what it’s called, will reboot him. He’s dived into the neck of the young, so he will get new life.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge