First they came for our large sodas; now, they’re back for the salt in our food. At least science was on their side the first time. Last week, a proposal was put forward in — where else — New York City to label any dishes on major restaurant chains’ menus that contain more than the recommended daily limit of salt. The average American eats an estimated 3,400 milligrams of salt per day, which the FDA would like to see come down to 2,300mg (about a teaspoon); the American Heart Association sets its bar even lower, at 1,500mg.

Beginning to see the problem? Finding thereal healthy limit is only the first issue to considerbefore making salt our new food pariah.

Questioning the guidelines

Last year, Danish scientists analyzed American diets and found that too little salt can be just as harmful as too much. What’s more, the FDA’s recommended daily amount could be nearly doubled without risk to health. Their study linked eating more than 12,000 mg of salt daily to a higher risk of heart problems and death, with the same effect seen in those eating the least amount of salt.

The scientists calculated the ideal range at between 2,645 mg and 4,945 mg per day — at the high end, that’s more than twice the FDA’s comparably generous recommendation. So what’s the real number?

The norm is too low

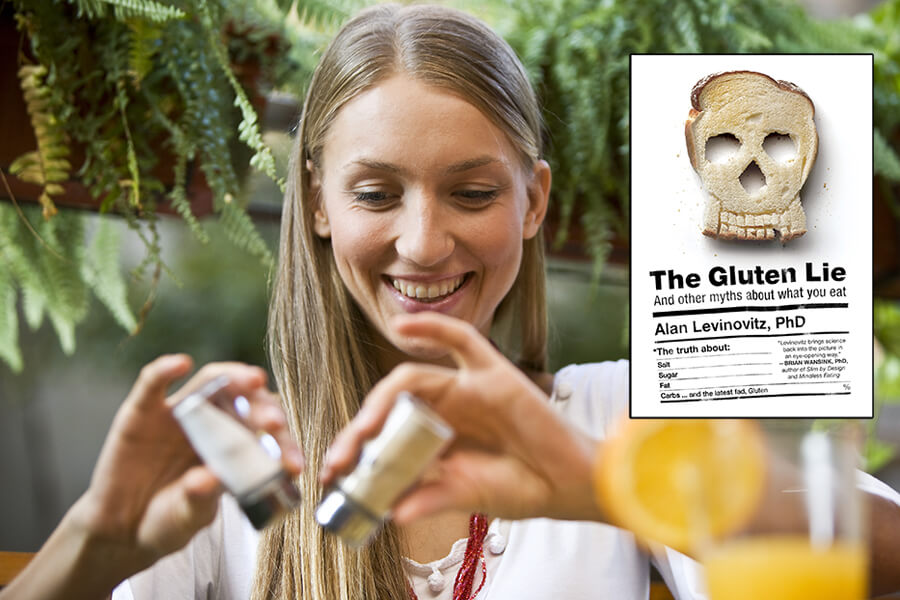

In his new book, The Gluten Lie, Alan Levinovitz highlights a nutritionist who developed Meniere’s disease, the treatment for which requires reducing salt consumption. When the nutritionist started exploring her options, she realized that the AHA’s guideline for salt intake was nearly the same for the average person as for someone with her condition.

“All of those people who have genuine physical reactions to foods get confused with a much larger population who are trying to use demonized foods to exert control over their own health,” says Levinovitz. “If the dietary guidelines came out, and they were honest, they would just say, ‘Eat around your recommended daily allowance of calories and make it varied.’”

The trouble with food science

“Studies in general, even studies of medicine, are difficult to run,” explains Levinovitz. Confounding variables abound, like the placebo effect, which can be especially strong when it comes to chronic conditions and makes it difficult to gauge how much of the effect is because of the dietary change. “You can’t just isolate the salt in people’s diet while keeping everything else constant,” he continues.

Add in genetic variants and cultural differences in diet, and it’s obvious why food data is somewhat speculative. “The great success of epidemiological studies is smoking,” Levinovitz adds. “But the reason we know that smoking causes cancer is because it’s isolated from other things. Cigarettes aren’t a part of every meal that you eat in the way that carbohydrates or salt are.”

Why not ‘just label it’

This isn’t New York City’s first attempt to regulate food — the Bloomberg administration tried to ban supersized soft drinks a few years ago. That movement, Levinovitz notes, at least has some scientific evidence showing that sugar might have an effect on our bodies that goes beyond excess calories.

“Your average American is consuming a perfectly fine amount of salt, but it’s not the same with soda,” he says. “What neither of them have, unfortunately, is studies that show that labeling is going to have a great effect on the salt consumption of your population.”

The evidence on calorie labeling is mixed, and a saltwarning label could have far-ranging effects. “In theory, labeling these dishes is not bad. But in practice, it’s not just going to make people anxious about that particular dish, it’s going to make them anxious about salt in general,” he says.

Unexpected consequences

When fats became the enemy in the ’80s, people replaced them with empty calories full of sugar. Cutting back on salt so drastically could lead to many people seeking out tastier alternatives that may be no healthier, or worse, than what we’re currently eating. Levinovitz talked with people already afraid to salt their food, struggling to serve their kids plain, boiled broccoli. But that just has the effect of teaching them (and yourself) that home-cooked meals taste terrible.

“If you want to encourage a healthy culinary culture where people eat diverse foods and home-cooked meals,” says Levinovitz, “the last thing you want to do is demonize salt through forced labeling so people are scared to put it on their food at home.”

Don’t ruin your appetite

“To people who suffer fromdietary problems, whether they are obese and want to lose weight or they suffer from stomach issues, I would tell them as any doctor would: Stay away from the Internet. Go to a physician or registered dietician, tell them the goals you want to accomplish, and the physician or registered dietician will help you achieve your goal in a responsible way,” Levinovitz says.

For the rest of us just trying to eat healthier, he has a common-sense philosophy: “Realize how incredibly liberating it is to treat food as something joyful and not as an opportunity for salvation or damnation.”