George Wohlreich couldn’t find his skull.

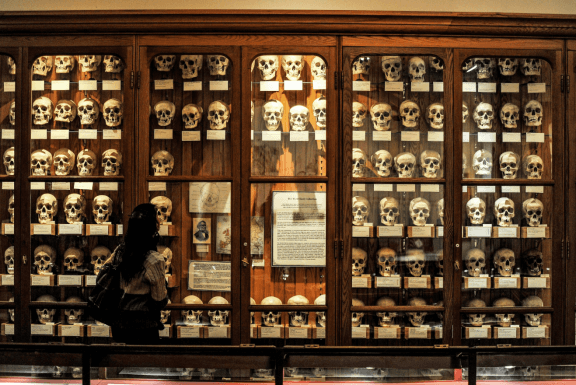

The CEO of The College of Physicians of Philadelphia stood on the Mütter Museum’s mezzanine and peered at more than 130 mounted craniums in a glass display and rotated his wrist.

“The castration guy,” Wohlreich said.

The college, which operates the museum dedicated to medical history, organized a preservation program in which admirers can adopt one of its skulls.

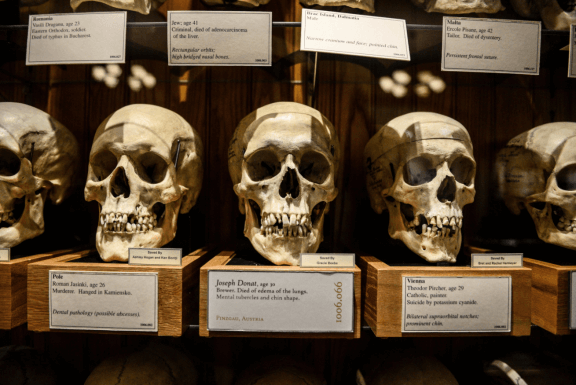

For a $200 donation, the museum will restore and remount one of its brain boxes — donor’s choice — and add a name card next to the artifact for 12 months. A $1,000 donation ensures the name card will sit next to the skull for 10 years, and the donor will receive a replica.

“Where is Andrew?” said Anna Dhody, museum curator. She scanned the display, looking for Andrejew Sokoloff.

Wohlreich and his wife adopted that one.

“This guy tried to castrate himself,” Wohlreich said.

Because he’s part of another exhibit, he’s outside his box.

Why that particular one?

“Because the one I really wanted was taken by the lady to my left (Dhody),” Wohlreich said. “I never pull rank around here.”

He wanted Geza Uirmeny, who, at age 70, intentionally cut his throat in an attempt to commit suicide, but survived. He lived until about 80, and apparently, “without melancholy,” Dhody said.

These are just several of the interesting characters that once inhabited the artifacts, and were collected by Joseph Hyrtl, an Austrian anatomist, in the early 1800s. The museum bought the skulls and other artifacts in the late 1800s.

With his collection, Hyrtl tried to debunk the pseudo science of phrenology, which alleged the size of the skull indicated the person’s intelligence, and essentially, that the caucasian race was superior.

But Hyrtl, a devout Catholic, believed that only God could give you a station in life and not just by category.

“So he methodically and scientifically collected these skulls, because what he wanted to show,” Dhody said, “was there is such difference in the shape, size and structure of the so-called homogenous race.”

Essentially, Hyrtl’s point was that “you cannot make these grand, sweeping statements about the superiority of one race over another because there is so much inherit differences between each skull,” Dhody added.

You can give them a home

The skulls are displayed on original cast iron, three-pronged mounts.

Dhody said the prongs reach up into the hole reserved for the spinal cord. Vibrations caused by visitors strolling by the case rattles the skulls and chips away at the delicate, bony structures. The museum designed new mounts with foam.

“It’s putting all of the weight of the skull on one small point,” Dhody said. “It’s not ideal.”

____________________

Follow Tommy Rowan on Twitter: @tommyrowan

Follow Metro Philadelphia on Twitter: @metrophilly

Follow Metro Philadelphia on Facebook: Metro Philadelphia