Until recently, Anna Chapman roamed the streets of New York on the trail of classified information. But her credentials were hardly stellar, according to General Oleg Kalugin, the former head of KGB counterintelligence. “Maintaining people like Chapman as spies is absurd,” Kalugin tells Metro.

“It just shows that the FSB wants to impress the Kremlin. As in the past, today’s real spies are diplomats, journalists and scientists and real businesspeople. And as in the past, the United States is the FSB’s most important priority.”

After the collapse of the Soviet Union, the KGB was renamed FSB. Kalugin spent part of his career as KGB chief in the U.S., posing as a student, a Radio Moscow reporter, a professor, a Czech refugee and a Norwegian journalist.

Kalugin has been sentenced to 15 years in prison by Russia’s current regime, but the U.S. has refused to extradite him. Even so, Kalugin met with Metro in Washington alone and without disguise. According to his estimate, 60 percent of Russia’s embassy staff in Washington are involved with intelligence — only slightly fewer than the estimated 70 percent during the Cold War.

“The Cold War never died,” says Fred Burton, vice president of intelligence for the forecasting firm Stratfor. “The FSB has been very active, especially since 9/11, when many FBI agents were reassigned to deal with counterterrorism.”

And Russia is far from alone. China, India and Israel have maintained or increased their operations since the end of the Cold War, mainly targeting the U.S. Cuba, Venezuela, Iran and Pakistan run large spy networks as well.

“The Israelis categorically deny that they conduct intelligence operations against the U.S., but of course they do,” says Burton, a former counterintelligence agent.

Today, jihadist groups and Mexican drug cartels maintain spies, too. “All sponsors of terror are involved with espionage,” notes Burton. “They understand its value.”

Like foreign countries, terrorist groups recruit on the basis of loyalty, targeting emigrants who might be disappointed that their lives abroad didn’t turn out the way they had hoped. Drug cartels, on the other hand, recruit spies with bribes and blackmail.

Scoop: New day, old tricks

Even in a high-tech era, spies use old-fashioned techniques.

Because counterintelligence agents monitor computers and cell phones, spies often rely on shortwave radios. Dead drops are another common trick; spies can exchange information by leaving a bag by a bush. In a recent case, agents delivered secret documents in shopping carts.

“Agents develop as many contacts as they can,” explains Oleg Kalugin, the former KGB counterintelligence chief. “That has the added advantage of confusing counterintelligence agents. But they make sure they call their contacts, not vice versa. I used to say that I was a correspondent and traveled a lot.”

Putin vs. Kalugin

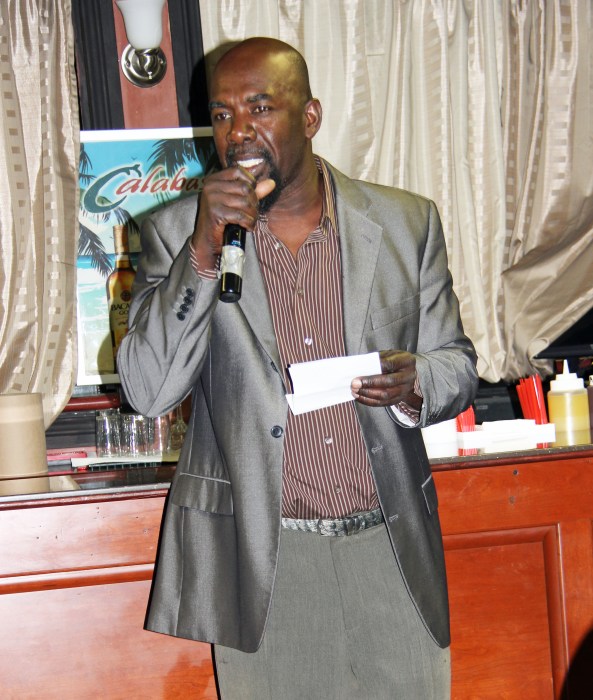

In almost four decades working for the KGB, Oleg Kalugin amassed a superior list of achievements.

While stationed in the U.S., he ran almost 300 sources. One of them was John Walker, who gave Kalugin hundreds of CIA and Pentagon contacts. As head of KGB’s counterintelligence, Kalugin planned the legendary umbrella murder of Bulgarian writer Georgi Markov.

Among the spies working under Kalugin was one Vladimir Putin. “But now he hates me,” says Kalugin. “It’s because I’ve called him a war criminal.”