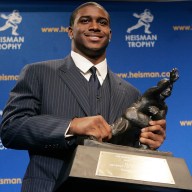

People show pictures of missing women during Mexico’s ‘One Billion Rising’ flashmob against violence against women.

People show pictures of missing women during Mexico’s ‘One Billion Rising’ flashmob against violence against women.

Credit: Getty Images

On one January day in Guatemala six women and two girls were murdered.

“I haven’t been able to find a reason for the murder,” says mother Rosa Franco, whose 15-year-old daughter Maria Isabel was killed. “But such is life as a woman in this country full of corrupt authorities. I suspect several people, including a 45-year-old drug dealer who’d been harassing my daughter since he asked to go out with her but she refused.”

Welcome to our 21st century world, where one third of women will become victims of violence at least once in their lifetime. In Peru, their fate is even worse: “We have 10 femicides a month,” says María Ysabel Cedano García of the local women’s rights group Demus.

Perhaps even more perplexing is that violence against women remains common in developed countries. In Sweden, 46 percent of women report having been victims of violence. Women and girls make up 80% of people trafficked globally each year.

“Violence against women is a hidden epidemic, and hidden is a very important word,” notes Ann Veneman, the former Executive Director of UNICEF. “We all know that women are getting raped as a weapon of war in places like the DRC, but in the developed world the problem is hidden.”

Most violence against women occurs in their homes, committed by their boyfriends or husbands. “Partner violence often has a psychological component, which makes it harder to measure,” notes Markku Heiskanen, an expert in domestic violence at the European Institute for Crime Prevention and Control. “And women want to protect their partners. When they talk about previous partners, they mention violence much more.”

Young women, especially, bear the brunt of men’s aggression. Nearly half of all sexual assaults worldwide are committed against girls under 16.

“In many cases it’s girls from difficult homes who are trapped by men who say they love them but are really johns [pimps],” says Veneman. “What goes on in these cases is quite extraordinary, and it’s happening in North America and Europe.”

But there’s good news. Safe houses for women are being built, even in countries where violence against women has long been tolerated. Victims are being trained in occupations so they can earn their own money. In India, the Delhi gang rape of a young woman led to unprecedented protests. And in China, the death sentence of Li Yan, a woman convicted of killing her husband after being abused by him for years, caused a rare public outcry.

On Valentine’s Day this year, the global organization V-Day arranged One Billion Rising, a record-breaking event for protesting violence against women. And this month global leaders convene at the UN headquarters in New York to address it.

A generation ago, violence against children was considered acceptable; today it’s frowned upon, and in many countries it’s banned.

“That shows that society can change the situation if it acts,” explains Heiskanen. “Every man carries violence inside him. Every human feels aggression, but perhaps women have been educated to use it less. We can educate men, too. They are rational beings. If they’re told what’s allowed and not, they’ll behave accordingly. We need courses in how to be a man.”

Victims of rape, FARC find hope in girls’ home

When Monica was five years old, her stepfather raped her. But when she told her mother, her mother informed her stepfather.

“Then he threatened to kill me and do the same to my sisters,” recalls Monica, now 16 years old.

After six more years of abuse, Monica ran away and joined FARC, Colombia’s rebel group.

“I wanted to belong to a group because at home I had nobody,” she explains. But after hearing that several boys had been killed, she escaped.

Monica is now being cared for by Taller de Vida, an organization in Bogota that supports former child soldiers. “

The most common reason the girls join this group is that they’ve been sexually abused by their relatives,” says Stella Duque, Taller de Vida’s director. “But having belonged to a revolutionary armed group creates big problems and emptiness in them.”

At Taller de Vida, Monica and the other girls get psychological counseling, attend school and perform theater and music. “I used to want to find my mother and kill her,” she says. “But now I want to find her and tell her that after all she did to me I’m happy.”

Q&A: “Vagina warriors celebrate success” — Susan Swan, Executive Director, V-Day

Metro: V-Day was founded after the Vagina Monologues became a global phenomenon. How can it be that, despite years of campaigning and events like the Monologues, violence against women remains so common?

Swan: V-Day just turned 15 years, and we asked ourselves, ‘How can we celebrate when one third of women are still victims of violence?’. But we’ve seen incredible progress. New laws have been passed. Women are doing amazing things, like running shelters for abuse victims. Tens of thousands of activists in 142 countries, including Libya, Iran and Somalia, have joined our campaign. People are realizing that if you help women you help your community.

Where have you seen progress?

Women are organizing. We’re getting emails from women all over the world telling us they’ll take action. In India, men and families are coming together in support of their wives and daughters. And in Mogadishu women recently organized a flash mob! Women are looking at the patriarchy in a different way. And men have been draw into this movement too, including Robert Redford and the Dalai Lama. We need more such men, and we need to invite men into the conversation. All of this creates a ripple effect. You need this movement in combination with legislation. Male and female members of the European Parliament have even created a ‘Vagina Lobby’. And remember that politics responds to people. It’s a stigma to our modern society that violence against women still exists.

Can you give me a success story?

We’ve helped with a healing program in the DRC called City of Joy. The women who attend are asked to bring what they’ve learned back to their communities, and boy, have they done it! We’ve seen a massive shift in attitudes. We call these women ‘the vagina warriors’. It’s truly inspiring.

Women in Iraq reduced to ‘breeders’ after war

Twenty years ago, Iraqi women usually dressed according to their choice, drove their cars freely, and had independent incomes. Indeed, when it came to women’s rights, Iraq was considered the most progressive country in the Middle East. Not anymore.

“Since the war started 10 years ago, Iraq has moved towards Islamist fundamentalism, and women are paying the price for it,” says Yanar Mohammed, President of the Organization of Women’s Freedom in Iraq (OWFI).

“Even in families that were liberal before the war, women are now simply seen as breeders who have no opinion.” The situation has deteriorated even though the Americans immediately after the war introduced a 25% women quota for the new parliament.

OWFI, based in Baghdad, provides shelter for battered women, even though the government has banned it from doing so. “Even if a woman’s life is in danger, we’re not allowed to shelter her,” says Mohammed. “The general attitude is that if a woman goes against the wishes of her community, she deserves to be killed.”

So Mohammad goes on sheltering women, even though it means she could be sent to jail. “The so-called war of liberation has turned the worst machos into leaders,” she says. “We have to fight back. They don’t have the right to turn millions of women into victims.”