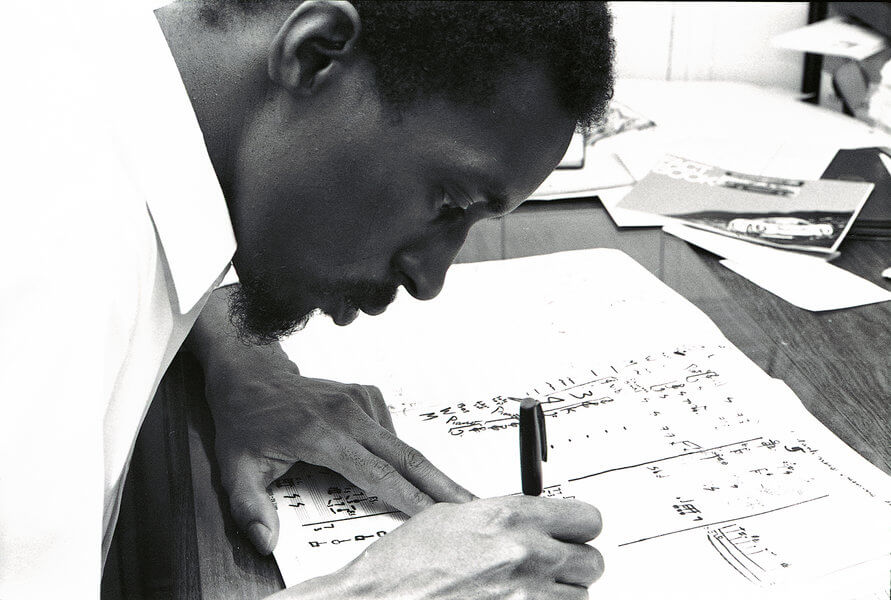

By the time of his death at age 49 in 1990, composer Julius Eastman was all but forgotten. A decade of erratic behavior fueled by drug abuse left him homeless, his career in shambles. Much of his music had been lost or scattered. It took eight months before the Village Voice took notice of his passing and printed an obituary.

More than 25 years later, Eastman’s music is enjoying a resurgent popularity; the composer has been the subject of a recent anthology of essays, “Gay Guerrilla;” a 3-CD set, “Unjust Malaise,” among other recordings; and appreciations in the New Yorker, the New York Times, The Guardian and other publications. Throughout this month, Bowerbird will present the first large-scale retrospective of Eastman’s music with four concerts at the Rotunda and an exhibition exploring his legacy at Slought Foundation. The project includes modern premieres of several compositions previously considered lost and rediscovered only after intensive, archaeological detective work.

“I hope that people will come away with a much wider understanding of Eastman as a composer, incorporating a much wider range of his musical styles,” says Bowerbird director Dustin Hurt. “I’d also like it to move past this tragic narrative that’s oft repeated but isn’t necessarily true.”

While Eastman’s death and final years were no doubt tragic, Hurt points out that the composer enjoyed a great deal of acclaim and attention during his lifetime. He was a renowned vocalist who toured with Meredith Monk; he performed with Zubin Mehta, Pierre Boulez and John Cage, gave recitals at Carnegie Hall and Lincoln Center, and was nominated for a Grammy. “He was pretty famous,” Hurt says, “or as famous as you can be in new music.”

Eastman also gained notice, then and now, for his provocative approach, far removed from the heady abstractions of much new music of the time. His titles included derogatory racial and sexual epithets, defiantly asserting his identity as a gay African-American man. This confrontational boldness, Hurt concludes, may have been Eastman’s fatal flaw as much as it was a key component of his art.

“We have some fantastic interviews where Eastman talks about being an artist to the fullest and not compromising, about being completely oneself. Ironically, perhaps sadly, this striving to be a ‘complete artist’ may have actually been the thing that led to his downfall: the refusal to participate in the normal routines of life.”

Bowerbird’s retrospective spans much of his career, including unusual works for ten cellos or four pianos. It also captures the stylistic range of work, from early minimalist pieces that incorporate influences from pop music and improvisation to his later, more daunting and dissonant music. It will no doubt fuel the intense interest surrounding Eastman’s work, and be a key event for both scholars of his music as well as new listeners intrigued by a long-silent voice.

Julius Eastman: That Which is Fundamental

Concerts: May 5, 12, 19 & 26

The Rotunda

4014 Walnut St.

$12-$25

Exhibition: May 4-28

Slought Foundation

4017 Walnut St.

Free

thatwhichisfundamental.com