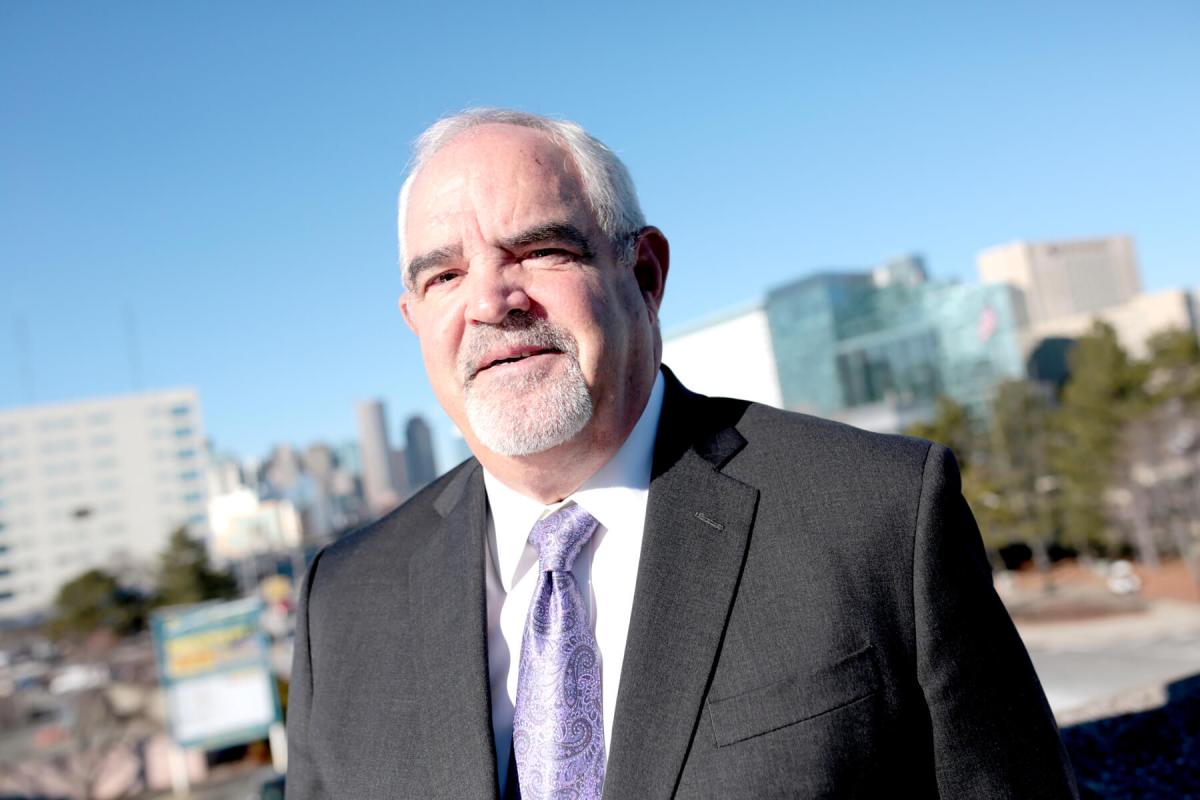

He’s been known for decades as the guy you called when if you were really deep in it: Accused of stabbing the son of a Boston cop more than two dozen times before leaving him to die in a Revere alleyway? Running a ship-full of guns to the IRA — yeah, as in the terrorist group — from Massachusetts? When the police or prosecutors wanted to make an example of you and your alleged wicked ways, you called Anthony Cardinale, a 64-year-old Belmont resident who has been practicing law for 37 years.

Cardinale wanted to be an attorney from a young age. He split his youth between Manhattan and New Jersey and worked at his family’s restaurant — Delsomma — in Manhattan’s Theatre District. He saw the reverence his father and his uncles treated the doctors and attorneys when they came in to the restaurant. Since he was never scientifically inclined, he decided he wanted to be a criminal defense attorney from a very young age. Cardinale, a boxing enthusiast who played linebacker at Wilkes University, attended Suffolk Law and has stuck around the area since. As a young lawyer he was taken under the wing of F. Lee Bailey — of OJ Simpson fame. By the time he was 32, he was representing North End mob boss Gennaro Anguilo, who told Cardinale he always wanted to be a criminal attorney. “Well,” replied Cardinale. “You got half of that.”

By 34, he was representing Anthony Salerno, a boss in the Genovese crime family, in the so-called “Commission case,” considered at the time to be the largest organized crime case in the country at the time. “All these guys that attain those positions, are extremely smart guys, they didn’t get there because they were stupid. They got there because they are very, very bright guys,” he said.

In the early 1990s, he represented John Gotti – the so-called Teflon Don and patriarch of the Gambino crime family. He described Gotti as a smart, tough man who could be wickedly funny even when he knew the case was going down in flames and he would be most likely going to jail for a long, long time. “He would never even say that the mob existed,” he said of Gotti. “That’s how ingrained it was.”

What does Cardinale make of the term mob lawyer?

“If it’s done pejoratively, if someone is saying it as if it means something negative, of course I don’t like it,” he said.

While representing Patriarca crime family boss Frank Salemme in the 1990s, Cardinale was instrumental in unmasking James “Whitey” Bulger and Stephen “The Rifleman” Flemmi as federal informants, said Brian Kelly, a former federal prosecutor who now works for Boston’s Nixon Peabody. Cardinale made a motion that forced the unveiling of all federal informants connected to Salemme’s case. The FBI shielded Bulger and Flemmi because they were getting the feds arrests and convictions, he said. Careers in the FBI are made on turning informants, and Bulger and Flemmi were prized. “His filing set a lot of things in motion,” said Kelly, who described Cardinale as “an excellent, hard working, dogged attorney.

“I think when you know you’re sitting across from someone who is very good you go the extra mile to make sure you’re prepared,” said Kelly. “There was always that feeling with him; the other side knows what they’re doing so you better know what you’re doing.” Another former prosecutor, Gerard T. Leone Jr. called Cardinale a “well-respected, well-regarded lawyer and for good reason.”

“He’s always well-prepared. He’s tough as nails and he’s a zealous advocate for his clients,” said Leone.

Martin W. Healy, the chief legal counsel and chief operating officer of the Massachusetts Bar Association, recalled working with Cardinale in the early 1990s to lobby against the state legislature creating a RICO (Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organization Act) statute based on the federal law used to puncture organized crime. The fear among criminal defense attorneys was that the law would be abused and misapplied. The state still doesn’t have a RICO law. “People were mesmerized at his intricate knowledge of the statute,” said Healy. “He is so unassuming. He’s not full of ego. He knew it was a flawed law and he knew it had real effects on real people.” Healy added, “I don’t think there’s any other attorney I’ve met locally that matches his skillsets. His knowledge base and his ability to communicate using a very common sense approach. He deals with very complex, esoteric statutes like RICO and he can boil it down. He relates very well to a jury.” While Cardinale made his name representing mafiosos, he hasn’t taken a mob case in six years. The last one involved the Boston-based Carmen “The Cheeseman” DiNunzio, an alleged associate of the Patriarca crime family perhaps best known for his obesity. The structure of New England’s underworld shifted. People were thrown in jail. Gangsters ratted on other gangsters. Whitey Bulger went on the lam. Others died — Gotti, Anguilo and Salerno, for instance, have been dead for years. Calls from alleged mobsters stopped coming. “I don’t get those calls anymore because there’s no one to call me,” he explained. “There’s no mob cases around anymore. There’s nothing left. It ran its course.”

So how does he keep busy? He mostly deals with white collar crime — tax and Medicaid fraud cases and still does drug crime cases and public corruption cases — he recently won acquittal of a prolific builder in Rhode Island. Asked if he misses those cases and the headlines that go along with them, Cardinale concedes he likes being the guy on speed dial when Public Enemy No. 1 gets nabbed.

“I always took that as a compliment,” he said, sitting in his dog friendly office — the resident Boston terrier is named Fred — on Summer Street in Southie.

Any case he wouldn’t take on? Yes, he said. He wouldn’t take on clients accused of animal cruelty or clients accused of sexual violence involving kids.

“I couldn’t be fair,” he said. “I couldn’t do it.”

Asked if he ever has to morally justify what he does to himself, Cardinale told a long story. A client of his, who he refuses to name, was alleged to have killed a man in brutal fashion.

The prosecutor represented that blood was found on his client’s boots, specifically the toes of his boots, where the prosecutor claimed he had repeatedly kicked the victim.

His client told him that was impossible; he didn’t deny he was at the scene of the crime, but he said he had burned all of his clothing he wore that day. Cardinale was able to get a forensics expert to admit there had been a clerical error in the forms used to process the lab tests of the boots. There was no blood. He thought his client had committed the murder and had questioned whether he could and should represent the guy, but the government’s behavior aggravated him enough to press on with the case, which he ultimately won. “What my client did was horrible but what the government did was worse,” he said. “That happens in a lot of cases, every day, in every courthouse. That’s what we do as defense attorneys, we stop cops, prosecutors and judges from playing God.”

Anthony Cardinale talks Whitey, Gotti and the FBI

Nic Czarnecki/Metro