Note: The Q&A was preceded by a screening of the film. This story contains extensive spoilers, including the ending.

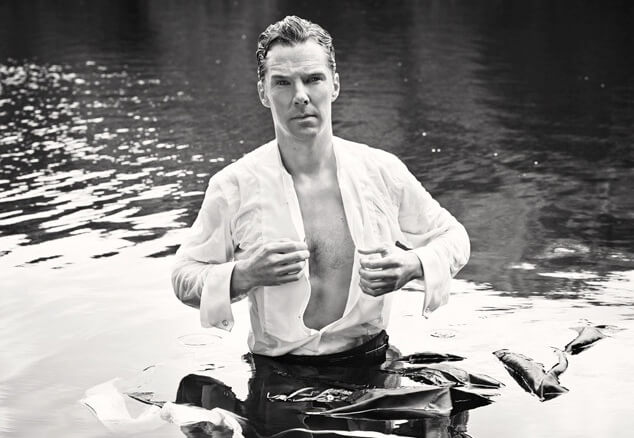

Turns out that when Benedict Cumberbatch is tired, he merely does his job even more thoroughly than usual.

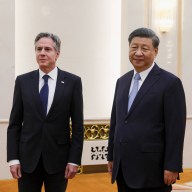

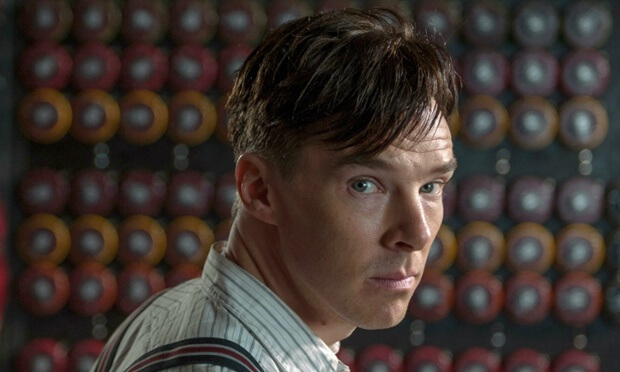

The actor was at the 92nd Street Y in New York City on Sunday to promote “The Imitation Game,” about Enigma codebreaker Alan Turing, as part of the Reel Pieces series. He arrived after walking the Bryant Park red carpet for “Penguins of Madagascar” (in which he voices a wolf and, presumably, got some training on the word “penguin”), having flown in that morning after receiving the Actor Award at the Hollywood Film Awards on Friday in Los Angeles. (His transcontinental press tour will continue through next month as he gears up to promote “The Hobbit: The Battle of the Five Armies.”) But instead of rendering Cumberbatch, like it would any other human being, less coherent and more curt, it all only seemed to result in his answers getting longer and more wandering. During the late-night session – the Q&A didn’t begin until after 10 p.m. – Cumberbatch fielded questions from host Annette Insdorf and, when they weren’t taking the microphone only to express effusive praise, the audience. In preparation for the role, Cumberbatch pored over letters and met with surviving members of Turing’s family to tease out the nuances of his mannerisms and personality. The film depicts a man at times painfully awkward, and others callously arrogant, to the people around him, but those who knew him spoke of a fundamental decency – someone who made them laugh as well as think. “They talked about a man who was incredibly respectful of them as human beings, who would treat them as adults, who didn’t treat them as children, he would treat them as equals,” he said. The party trick of the man who would invent modern computing? Playing chess with his back to the board. Details like that served to humanize a figure who on the page reads as intimidatingly intelligent. Cumberbatch is obviously a fan, happy to be the self-proclaimed designated spokesman for Turing. It’s somewhat ironic that the legacy of a man he describes as “an incredibly fragile child” was the modern computer which can think about anything, but not feel. “He felt everything so keenly,” Cumberbatch said. “Everything he experienced influenced his mind, which amplifies the volume of the tragedy of his death.” (Turing committed suicide while undergoing two years of court-ordered chemical castration, which he chose over prison after being convicted of homosexuality.) Turing developed a stutter as a young man, and was “treated immediately as different” for that even before he came into his sexuality. But more than anything else it was the sudden death of the love of his life, Christopher Morcom, as young friends at school, that shaped Turing, and it was that discovery that Cumberbatch said most helped guide his performance. “[Turing] wanted to believe there was some kind of afterlife, a way that [Morcom] was still present. And he came to the conclusion, as that grief cooled a little bit, that he would keep it present by giving life to the legacy of this inspiring man.” Cumberbatch gave a lot of credit to Graham Moore, a first-time screenwriter whose work apparently arrived fairly fully formed, both in structure and dialogue. But the “Star Trek Into Darkness” star wasn’t immediately onboard: “The first time I saw the script, I was playing Khan and in a very different headspace.” When he learned it was at the top of Hollywood’s Black List (scripts that industry professionals have rated highly but no one has acquired), he gave it another pass and was so taken with Turing’s story that he pursued it even though another actor was attached at the time. “I was onboard with the idea of being onboard,” he said. “Without being sort ofstalkerish or weird, I kind of became… a stalker and weird.” He wooed the producers, appropriately, with his knowledge of Turing’s significance and desire to tell his story to a broader audience.

Cumberbatch’s enthusiasm chills to an anger he still feels while talking about the events that led up to Turing’s trial, the impact of his work on not just World War II but the daily lives of certainly everyone in the audience. “Why don’t people know about this man, why is he not on the cover of not just science books but history books?” When the official pardon issued to Turing by the U.K. government is brought up later in the evening, Cumberbatch maintains that it was too little, too late. “[Alan Turing is] the only person who has the power to forgive in my mind, but he can’t because we destroyed him.” He was surprised, in a good way, by the choice of Norwegian Morten Tyldum to direct the film, saying that his “skewed, atypical” approach saved the biopic format from its own cliches.

Cumberbatch rejected that playing physicist Stephen Hawking in a 2004 BBC movie prepared him at all to take on Turing. “Stephen is an extrovert, is incredibly sly and quick-witted,” and comparisons between the men are “thin on the ground.” Had he lived, Turing wasn’t destined for the limelight like tech rock stars Steve Jobs or Bill Gates, Cumberbatch said – then again, he conceded, addressing the audience, “The most unlikely people end up on stages talking about stuff.” (They reassured him he’s fine being up there.) What got left on the cutting room floor was Turing’s death, with the policeman who’d interrogated him finding his body. The scene “didn’t feel right when we were doing it,” Cumberbatch said. Instead, the final shot is a celebration as the BletchleyPark team cast their papers into a bonfire, dancing and laughing and knowing that the destruction of their work is insignificant because their achievements would live on. But the film does touch on the end of Turing’s life, years later at age 41, physically and mentally enfeebled by the chemical estrogen, when he is visited by Joan Clarke (KeiraKnightley), the woman he’d recruited to Bletchley and nearly married. “[It’s] about somebody telling him something that he never had told to him in his life: that he did matter. That he was different and wasn’t normal was hugely important to the world. … It was our way of thanking him in the structure of the film.” “The Imitation Game”premieres in the U.S. on Nov. 28. F ollow Eva Kis on Twitter@thisiskis.

Benedict Cumberbatch became ‘a stalker and weird’ to get ‘Imitation Game’ role

Eva Kis, Metro