It’s sadly become a daily headline in the United States; the leading cause of death in the country for people under the age of 50 is a drug overdose. In fact, more than 64,000 Americans died in 2016 due to an overdose (compared with roughly 40,000 in car accidents). And the problem isn’t going away. But what’s at play in this epidemic?

We spoke with Dr. Deni Carise, Ph.D., the Chief Scientific Officer at Recovery Centers of America, to learn more about the culprits, and how we’ve gotten to where we are today.

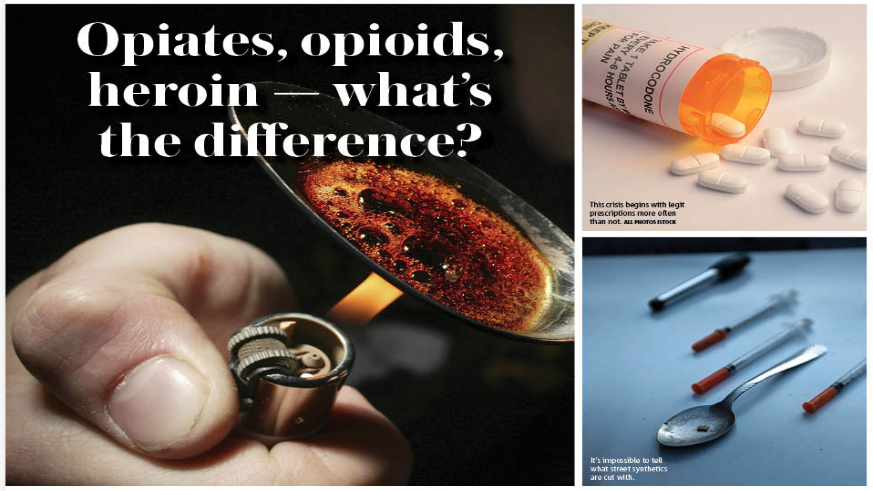

First of all, what is the difference between an opiate, an opioid and heroin? “The most important thing to know is that they all work on the same area of the brain, and are all addictive,” says Carise. “They allow you to experience euphoria, they decrease your heart rate, and though different in strength they can all kill you. The only difference between them is that when prescribed you know exactly what you’re in for, whereas when purchased on the street in different forms it’s anyone’s guess.”

Turns out almost everything we think of as an opiate is, in fact, an opioid. Opiates must be derived from the poppy plant (an example of this is morphine). OxyContin, heroin — all drugs that used to be referred to as “narcotics” before the late 1990s, when pharmaceutical companies went to great stakes to convince healthcare providers and consumers that their pain relief medications weren’t highly addictive, are opioids. So doctors, who didn’t want their patients in pain, started handing out prescriptions in record numbers, and the general public, even more, averse to pain, started asking for products by name. The result was an explosion in the number of people dependent on these drugs. And as the cost of a prescribed medication would go up, and availability goes down, synthetics popped up on the street to fill that void.

Let’s break down what synthetic versions of prescription drugs are plaguing the country because 75% of people in treatment for heroin started with a prescription opioid.

Once prescriptions become unavailable or too expensive, many look to heroin as a next step. It’s cheap — roughly 10% the cost of the prescription medication — and it’s also abundant. “600 people try heroin for the first time every day in this country,” says Carise, “and it enters the brain much quicker depending on the route of administration.”

After heroin, we have fentanyl. It’s an incredibly powerful opioid that’s 50-100 times more potent than morphine. And though it used to be prescribed just for severe pain directly after a surgery, it’s now being produced on the street. The major problem with street drugs is that no one knows exactly what’s in them — one day’s bag of heroin may be pure, and the next day’s bag (which a user may take just to avoid getting sick rather than getting high) could be laced with fentanyl, and result in an overdose.

A really scary option on the black market is carfentanil. It’s only approved use is by veterinarians on large animals, such as 14,000lb African elephants. This drug is 10,000 times as strong as morphine and is being used to cut heroin. “A dose the size of a grain of salt can kill someone by just coming into contact with your skin,” says Carise. “It’s colorless and odorless, so you can just inhale it and overdose. People don’t ask for carfentanil, but unfortunately, it finds its way into other street drugs (even marijuana).”

When a person is suspected of suffering from an opioid overdose, the drug Narcan has been “tremendous and profoundly useful reviving the people who have overdosed on heroin,” says Carise, but unfortunately not when it comes to carfentanil. “Carfentanil lives longer in the body, and outlives Narcan,” she says.

“In the end, they all can kill you.”

The government has made certain strides to curb the problem by setting in place prescription drug monitoring programs (thus outing so-called “Doctor Shoppers” to mindful healthcare providers), but that does nothing to change the culture and care when people resort to using street drugs to manage their pain.

“We need to make treatment more available,” concludes Carise. “21.2 million Americans have a substance abuse disorder, and only 2.5 million receive treatment, that is only 10% of people with the disease.”