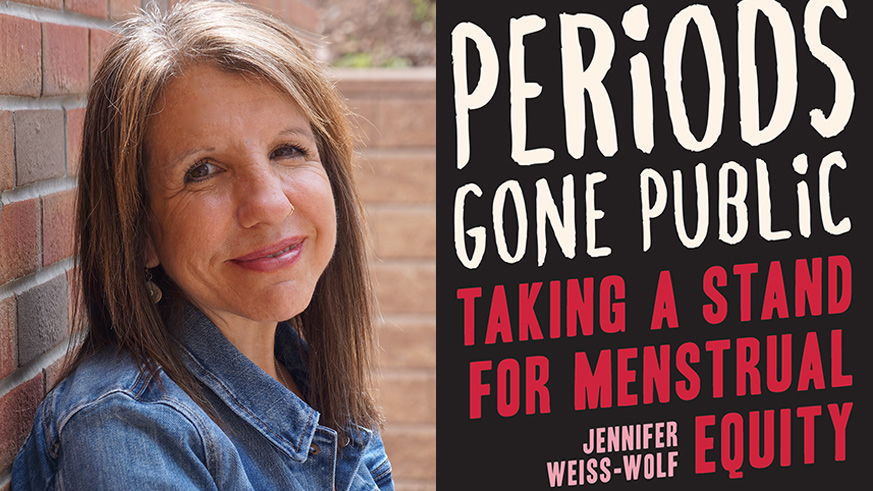

Period activism is having a moment — and Jennifer Weiss-Wolf is a key player.

The NYC-based lawyer hadn’t thought about menstruation as a political issue until one day in 2015, when some kids in her community were doing a collection drive of pads and tampons for their local food pantry.

“That was the first time I considered the notion of what it means to have access to menstrual products, and people who might have a hard time affording them,” recalls the vice president for development at NYU School of Law’s Brennan Center for Justice. “I started thinking of it in terms of systemic change, about how our laws could accurately reflect the reality that this a monthly reoccurrence for half the population.”

So Weiss-Wolf began writing and advocating for menstrual equity. In the fall of 2015, she partnered with Cosmopolitan to launch a petition on Change.org to eliminate the tampon tax. Since then, 24 states have introduced legislation to exempt the tax on menstrual products, and four states — Illinois, Florida, Connecticut and New York — have removed it. Weiss-Wolf also worked with New York City Council Member Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, who helped pass a law in 2016 requiring free menstrual products in public schools, shelters and correctional facilities in the city.

Now, she’s written a book, “Periods Gone Public: Taking a Stand for Menstrual Equity,” which chronicles this wave of period activism and charts how we might move forward.

It’s more than the fight for policy changes: Over the past couple years, a social movement has been gaining momentum. Weiss-Wolf recalls in April of 2015, when a woman ran the London marathon with period blood “free flowing” down her leg, both because it was more comfortable and as a statement against society’s stigma. Or that August, when Trump remarked after a contentious Republican debate that moderator Megyn Kelly “had blood coming out of her whatever,” it sparked social media backlash, with users tweeting back at Trump with the hashtag #periodsarenotaninsult. New “period-positive” startups, from makers of period underwear Thinx to organic tampon company Lola, introduced menstrual product innovations, with the goal of making the experience of monthly bleeding safer and more comfortable.

Normalizing conversations around menstruation is half the battle. “The stigma, is in part, how we got here,” she explains. “[It’s] rooted in all kinds of cultural and religious and misogynistic views about women and their bodies. If we bring menstruation out of the shadows, it makes it a whole lot easier to talk about what the problems are.”

A major issue is the lack of access to menstrual products, which the United Nations Human Rights Office of the High Commissioner has called a human rights violation.” Weiss-Wolf points out that paper towels are free in public restrooms, but tampons will cost you 25 cents. “On what planet did we decide that one is free and one is not?” she asks.

Jennifer Weiss-Wolf, along with Elizabeth Kiefer (Refinery 29) and Council Member Julissa Ferreras-Copeland, will discuss “Periods Gone Public” on Tuesday, Oct. 24, from 7:30-8:30 p.m. at Books are Magic, at 225 Smith St. Entry is free.