After a plan hatched by the Bristol County sheriff earlier this month put Massachusetts at the center of President Donald Trump’s border wall, lawmakers are pushing back.

Sheriff Tom Hodgson said inmate labor could cut down the price of the wall the president wants build between the US border between Texas and Mexico — which could cost as much as $25 billion — and he offered up his own prisoners for the job. In response, Democrat Sen. Michael Barrett of Lexington filed a bill last week that would require sheriffs to first earn approval from state officials before sending prisoners out of state.

Another bill, filed by New Bedford Rep. Antonio Cabral outright bans Massachusetts inmates from working out of state.

Both lawmakers said they oppose Trump’s border wall.

“If that’s what their motivation is — a political one about a wall — then that’s something they have to answer to and grapple with, but the fact is this project didn’t start because of the wall,” Hodgson said. The wall is just one of any number of projects he envisions under the umbrella of his pet project, Project NICE — National Inmates’ Community Endeavors — in which he and other sheriffs across the U.S. would mobilize inmates to provide relief efforts at natural disaster sites or work on major infrastructure projects. Barrett said he isn’t necessarily opposed to this program, but said “the critical thing that Sheriff Hodgson has to understand is he does not act by himself and under his own power. There is a state constitution and a system of checks and balances.” Inmates already participate in work programs, in which they are voluntarily do such things as cleaning up graffiti and keeping fields nice. Generally, prisoners make far less than a living wage — the going rate for American prisoners is anywhere from 30 cents to $7 an hour, according to the Economic Policy Institute. That’s far less than Massachusetts’ minimum wage of $11 an hour, but then again, prisoners don’t pay taxes or room and board. And cheaper labor means cheaper costs for taxpayers, proponents of prison labor argue. “That’s the head-scratching things,” Hodgson said, referring to the controversy he’s heard. “Why would anybody not want taxpayers to have more resources that would cost less money?”

Besides savings, Hodgson argues hard work builds character and gives purpose to the nearly 2,000 inmates he oversees.

“How many ‘thank yous’ do you think inmates are going to get by sitting in 10-foot cell all day?” he asked, noting work projects give prisoners a sense of accomplishment.

The difference between picking weeds and cementing bricks on the border, Barrett said, is about 2,000 miles.

“Nothing is more detrimental than putting thousands of miles between an inmate and his community,” Barrett said.

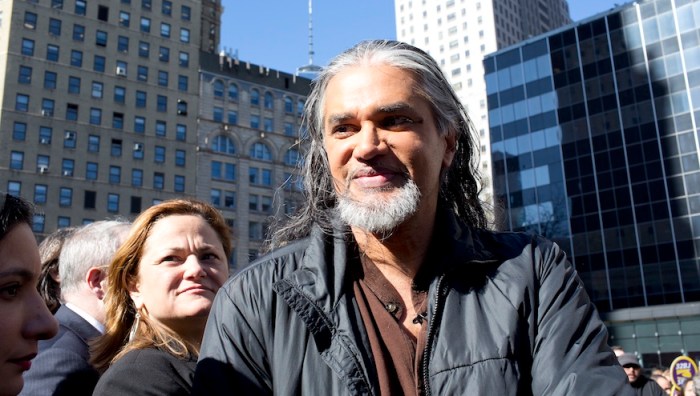

The state legislature has prioritized criminal justice reform as a major priority for the session, and Barrett said that means taking a look at programs that help prisoners re-enter society — working in their home communities and garnering family support are a huge part of that. “These are county jails where inmates spend up to two and a half years. They should be rotating out quickly, and they need all the programming they can get,” Barrett said. “We’re not able to do criminal justice reform if an inmate is on the Texas border.” But as far as prison advocate Leslie Walker is concerned, that’s a reality unlikely to be seen.

“While I appreciate any legislative effort to block the sheriff or any other sherifffrom threatening to take prisoners out of state for any purpose, as far as my office is concerned, the legislation is not necessary,” Walker, executive director of Prisoners’ Legal Services of Massachusetts said in an email. “Under our interpretation of existing law, the sheriff can’t take prisoners out of state.” Prisoners can be ferried out of state for various reasons at the approval of the commissioner of corrections, but also states that inmates being let out of confinement for work must find “employment within the commonwealth.” Hodgson contends interstate compacts give him authority to ship inmates and sheriff’s office staff to other facilities and departments around the country. These are the same compacts that enable law enforcement to send extra bodies to help when natural disasters or other tragedies strike. A review of state laws and compacts appeared to require the approval of the commissioner in addition to a county sheriff.

“Hodgson’s plan appears to be contrary to Mass law, but that’s never stopped him before,” James Pingeon, litigation director of Prisoner’s Legal Services said in an email.

Prisoner’s Legal Services has gone head to head with Hodgson on behalf of prisoners before, and Walker is known to be a vocal opponent of his policies, going so far, but she declined to comment further on Hodgson’s latest plan. “Sorry to decline, but my latest thinking is not to give the sheriff what he craves — publicity,” she said.

Barrett thinks he’s also after publicity, too, likening Hodgson to Trump and infamous Maricopa County, Arizona, Sheriff Joe Arpaio, the self-proclaimed “toughest sheriff” in America.

“I dare say he might take it as a compliment,” Barrett said. “But I happen think Mr. Trump has been trampling on civil liberties and I do not want to see Hodgson emulate him.”

Hodgson is no stranger to controversial agendas. In 1999, he tried reinstituting chain gangs and has faced civil rights lawsuits over his 18 years in office. In 2010, the state’s highest court ordered the sheriff’s office pay more than $700,000 after ruling a $5 a day charge for room and board to prisoners violated their rights. Whether current law prohibits Hodgson’s plan or not, for Barrett, the legislation can be seen as somewhat as an insurance policy against “people in the streets” and more lawsuits.

“If we don’t act as a legislature, we’re going to see lawsuits piling up,” Barrett said. “He’s been the target of lawsuits before for abuse of power and lost before the Supreme Court. These are expensive lawsuits that state’s going to have to pay for.” Barrett said he wants to see Massachusetts lawmakers take up this bill sooner rather than later due to the accelerating pace of business in Washington since Trump took office.