Bill Ciaccio pauses between bites of his turkey and cranberry sauce sandwich to talk about the dead woman on the toilet.

Ciaccio, 35, works for Aftermath, a company that specializes in trauma cleaning and biohazard removal, which is a nice way of saying they clean up dead bodies. These are the guys who get called to clean up thescene of a homicide or removea body that has been decomposing for weeks. Ciaccio is recalling a particular gruesome anecdote. An elderly woman has died while on the toilet, he said. The body hasbeen there for several weeks. Gravity, during the interim, hastaken over. The bowl is now filled with a mound of innards. Ciaccio’s crew spray the area with a disinfectant. The mound then starts to move because of the number of maggots in it. An attempt is made to flush the toilet. It starts to overflow. The shut off valve is located behind the toilet. One of his colleagues places his hand on the toilet seat to reach the valve. The seat breaks. “The guy goes shoulder deep into the goo and let’s out this primordial squeal,” said Ciaccio, a field supervisor for the company. “It’s the only time I’ve thrown up on the job.”

Aftermath was launched in Illinois in 1996 and has since expanded. Now, there are 22 offices across the country and about 110 employees. Ciaccio, who lives in Pawtucket, Rhode Island, works out of the company’s North Attleboro shop and services large swaths of New England. He’s been as far north as Bangor, Maine and Montpelier, Vermont. He estimates his crew does 150 biohazard cleanups per year. Most of his jobs are in Massachusetts. Ciaccio and Aftermathcolleague Andrew Whitmarshswapped such war stories in Mul’s Diner in Southie recently. Neither spoiled the other’s lunch, Whitmarsh choweddown on a burger and Ciaccio finishedoff his Thanksgiving sandwich with fries while they talked about cleaning up blood, guts and gore. Suicides by shotgun, they agreed, are usually large jobs. Sometimes, the entire room needs to be disinfected and some structural work needs to be done. A ceiling or a section of drywall will have to be replaced because of the debris or floors will have to be ripped up because of the pooling of fluids. They ticked off weird and disgusting anecdotes. There isthe time someone murdered someone else and painted 666 on the wallwith blood. There isthe time when a kitchen floor looked like it was moving in waves because of tens of thousands of maggots. There are times when the bodies could be smelled from the road. There is the time a mother stabbed her four-year-old todeath, almost decapitating her. A colleague of Whitmarsh’s quit after that job. “I totally understood,” said Whitmarsh.

Aftermath crews clean out the drunk tanks when someone has urinated, bled or vomited all over the cells. They clean out State Trooper cruisers when similar things happen in the back of those cars. They’ve done jobs for the T when need be. They clean out houses of hoarders.They don’t do chemical spills. And don’t ask them to clean out your meth lab. Other than that, they will clean the nastiest things you can think of. “This is not a glamorous job. You’re going to see some nasty things, you’re going to see some emotionally wrecked people,” said Whitmarsh.

Both talk about the need to compartmentalize your life when your dayjob is literally cleaning up death. People who can’t do that, they said, don’t last long.

“You have to have some type of release,” said Whitmarsh, an Illinois native who travels across the country as the company’s director of field operations.

Whitmarsh, who used to be an assistant golf pro before joining the company, still shoots in the low to mid-70s and enjoys going to the gym. Ciaccio also likes to work out during his off-time and is an avid reader; he’s currently reading the Lord of the Rings trilogyfor “about the 20th time.” They both saidthe job can be enjoyable. You’re meeting new people all the time, they said. On the road, you develop a camaraderie with your cleanup crew. Thinking about death so much, they said, can make you value life more. “You realize life is precious,” said Ciaccio.

The job, said Ciaccio, can be rewarding. Oftentimes, the cleanups allow people who are mourning, people who just weathered trauma, to begin some semblance of healing.

“I do actually enjoy the work,” he said. “I know that sounds kind of morbid, but the good part about it is helping people out who need your help.”

The dirtiest job: Meet the guys who clean up death

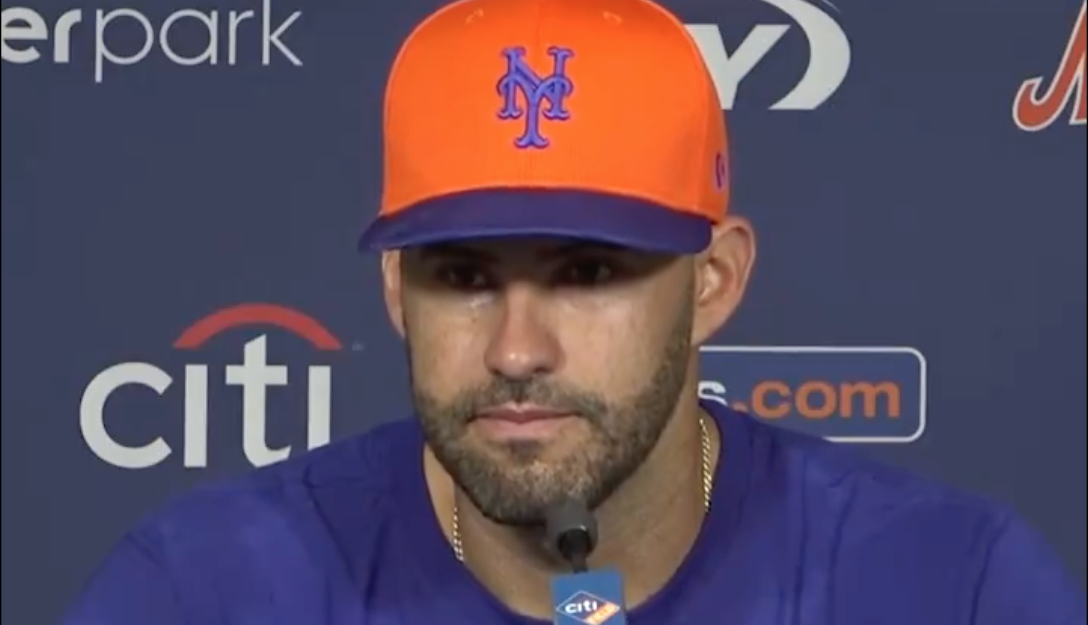

Nicolaus Czarnecki/Metro