WASHINGTON (Reuters) – Republicans are mobilizing thousands of supporters to monitor early voting sites and ballot drop boxes in November’s election, an effort that stretches the traditional definition of the roles of election observers.

Here’s the history of “poll watching” and how the practice may take on new meaning amid a surge in mail balloting spurred by the coronavirus pandemic and Republican President Donald Trump’s unsubstantiated claims that mail voting is riddled with fraud.

WHAT IS POLL WATCHING?

Poll watchers are part of U.S. elections dating back to the 18th century, with their activities controlled by state laws and local rules. People from both parties keep an eye on the voting – and each other – to make sure things go smoothly.

State laws call observers inside polling places different things, and assign them different roles. In some places, poll “watchers” are different from “challengers,” who can point out people they suspect aren’t legal voters. In other states, poll watchers also do the challenging.

Still other rules set boundaries on how close partisan supporters can stand outside polling places, as they try to whip up support for their candidates with signs, leaflets and other advertising.

Complaints about overly aggressive poll watchers are common. Sometimes, observers have used the ability to challenge voters’ qualifications in ways that discriminate against minorities, which has resulted in some court actions to end those practices.

In a 1999 city election in Hamtramck, Michigan, for example, challengers from a civic group called “Citizens for a Better Hamtramck” challenged 40 Arab-Americans who had “dark skin and distinctly Arabic names,” who were then forced by election officials to take an oath to prove they were citizens, according to a U.S. Justice Department consent decree. The city agreed to conduct training of its poll workers, and a federal examiner was appointed to oversee city elections through 2003.

In 1981, a Republican operation put armed men in uniforms emblazoned with “Ballot Security Task Force” outside polling places in largely minority areas during a New Jersey state election. After that incident, the RNC agreed to a consent decree that limited its ballot security operations.

That decree expired in 2018 after a federal judge declined Democratic attempts to renew it.

This year marks the first presidential election in nearly four decades in which the RNC can engage in ballot security activities without prior review and approval.

WHAT ARE THE RULES?

Regulations on who can “watch” voting, and the powers granted these observers, vary from state to state. In Pennsylvania, for example, poll watchers can observe the election – checking turnout and voting machines — and also challenge voters by taking their concerns to election officials. However, these challengers generally are barred from interacting directly with voters, or from making meritless challenges that slow down voting.

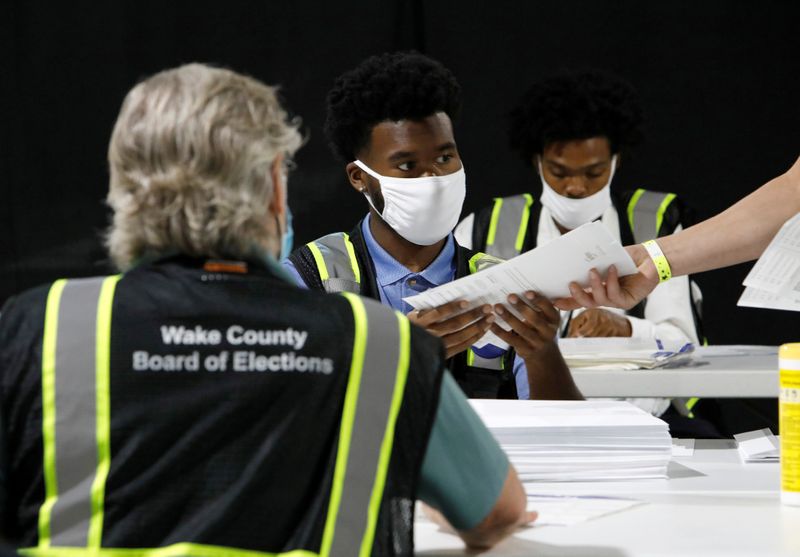

Qualifications for poll workers also vary. They typically are supposed to be registered voters; in some states they must be certified in advance by election officials. North Carolina requires that poll workers be of “good moral character.”

Observers also are permitted by law in states that conduct elections mostly by mail. In Oregon, for example, the law says parties and candidates can sponsor observers to watch election workers open ballots and count them, but these monitors must behave in a way that “will not interfere with an orderly procedure.”

Supporters of parties and candidates may stand outside polling stations with banners and other political advertising, an activity known as “electioneering.” But that also is subject to laws that vary state to state.

Generally, these advocates must keep a certain distance from the entrance, so as not to harass or intimidate voters.

In Ohio the border is 100 feet, and it’s supposed to be marked by two small American flags. In Florida and Georgia, the boundary is 150 feet.

WHAT IS DIFFERENT ABOUT THIS YEAR?

The COVID-19 pandemic means unprecedented numbers of Americans will be voting by mail and not in person in 2020.

President Trump has made unfounded claims that these ballots will be tainted by fraud. His campaign is seeking to recruit thousands of volunteers to look for irregularities – such as people dropping off more than one ballot in states like Pennsylvania where that generally is not allowed.

This effort is testing voting laws designed around in-person balloting on Election Day, election experts said. There is no rulebook for monitors trying to enter early polling sites, or potentially challenging voters in public who are trying to drop off their ballots, said Terry Madonna, a political science professor at Franklin & Marshall college in Pennsylvania.

ARE GUNS ALLOWED?

In a year that has seen armed militias confront protestors, some voting rights advocates are nervous about a return of gun-toting groups showing up outside polling places.

Some battleground states, including Pennsylvania, Michigan, North Carolina, Wisconsin and Virginia, are so-called open-carry states where citizens can carry guns openly in public. There are no laws on the books in those states explicitly prohibiting people from carrying firearms into polling places.

Still, state and federal laws make it illegal for anyone to try to intimidate voters.

Voting rights organizations say they will have thousands of lawyers standing by who would intervene with local officials or seek court orders to stop such activity.

(Editing by Soyoung Kim and Marla Dickerson)