Andrew Bujalski, one of the pioneers of “mumblecore” cinema, returns with “Computer Chess.”

Andrew Bujalski, one of the pioneers of “mumblecore” cinema, returns with “Computer Chess.”

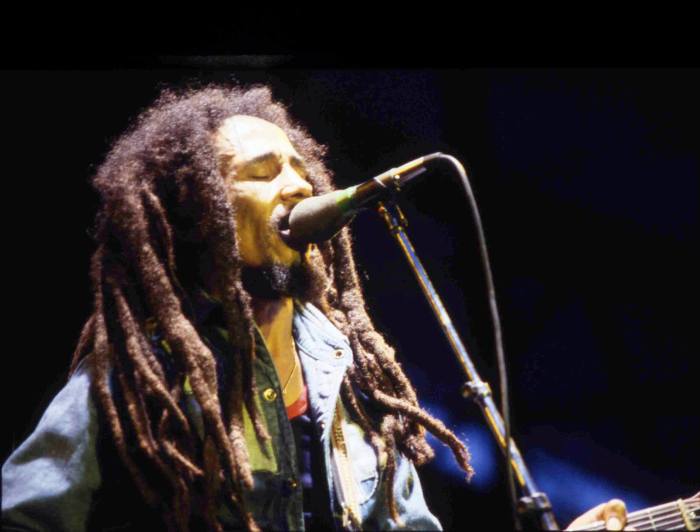

Credit: Getty Images

When he started touring the micro-budgeted “Funny Ha Ha” around in 2002, director Andrew Bujalski became one of the first to premiere a new kind, albeit retro, kind of American independent film. It wound up being dubbed “mumblecore,” by a press hoping to create a movement that wasn’t as concentrated, or as homogenous, as it was made to seem. Despite a stint writing for Hollywood, Bujalski has kept independent, making two more incisive, 16mm studies of inarticulate adulthood with “Mutual Appreciation” and “Beeswax.” His fourth film, “Computer Chess,” goes far afield: It’s a non-naturalistic, bizarre and surreal period piece, set in either the 1970s or 1980s, about a tournament, which he shot with the Sony AVC-3260, a black-and-white video camera invented in the 1960s.

What came first: The subject or the camera?

It was indeed the camera. For a decade I’d been making films on 16mm and getting asked over and over again why I still shoot on film. There’s some contrarian streak in me that thought, “Okay, you bastards. You want video? I’ll show you video.” I’d seen some images from this Portapak [old video camera] videos. There’s some stuff William Eggleston shot [with an old video camera] and later edited down into “Stranded in Canton,” which is just amazing and made me fall in love with the specific look of these cameras. And so I started to fantasize about what I could do, what would make sense, what narrative story would fit with the language of these images. And it cooked up slowly in my subconscious over the course of several years, to the point that I don’t remember where it came from specifically. It seems to be a very common question, “Where did this come from?” Because it’s not obvious. [Laughs] And it’s not obvious to me. I don’t know where it came from.

How did the movie come together?

We spent the early part of 2011 trying to pull together a much more conventional movie, with movie stars and everything. And we ran into a brick wall with financing. I was trying to get a film made because I was terrified if I didn’t make one soon I would never get to make one again. We went forward with this crazy idea I had. It was really nuts to sit there and realize I have no money. We have three months to pull everything together. We’re going to shoot it on an experimental camera we don’t know how to work yet. We have 30 speaking parts we haven’t cast yet. We probably need 50 extras. It’s a period piece. I don’t have a script. And it’s on a topic I don’t know anything about. [Laughs]

How did you come across the camera?

I jumped on eBay, and ended up finding one. I didn’t realize how lucky I was. When I was fantasizing about this movie, I got one on eBay, and fell right in love with it. But then once we started to gear up for productions and were looking for other cameras as backups, we were only able to find one more on eBay. Then we borrowed a third one from a private collector.

How difficult was it working with and maintaining them so they didn’t break?

Obviously no one on our crew had dealt with these cameras before. Just to get this 1969-era camera to communicate with 20th century technology — that turned out to be much more of a headache than any of us expected. When it comes to old technology, what you need is a friendly retired engineer somewhere with time on their hands to help you figure stuff out. And we were very lucky to find a guy up in a suburb of Austin who was a retired Sony engineer, who knew this stuff inside and out. There was a lot of trial and error. Pretty much everything about this movie was insane, and I don’t think we could have done it had we had more time to consider how absurd it all was.

You worked with a treatment, not a script, where your past films were very scripted. How much was on the page?

Structurally it was pretty much all there. That treatment does walk you through, scene by scene, what happens. Working without a conventional script just forced us to be better prepared than we would have been. From day to day we didn’t always know exactly what we were doing. The days we were shooting the tournament scenes in that big hall with 40 extras — those were very frightening. We had extremely limited resources. So on those days we had to be pretty meticulous, and have a shot list out in advance, because we didn’t have a moment to spare.

Most of cast are filmmakers themselves — editors, directors, even film critic Gerald Peary. Were they a little more receptive to this than regular actors?

I’ve directed films in the past that had even larger percentages of filmmakers in the cast. Generally those people tend to have a really good instinct of what plays and what doesn’t play and what feels right on screen. They have none of the baggage of a professional actor, who trains their whole life. I love professional actors, and there are plenty of professional actors in “Computer Chess.” But I’ve always felt that actors are trained to clarify, to always help the audience know where they are in the scene or the story. And that’s always something I’ve worked against in my work, which is why I’ve cast nonprofessionals. There’s a sort of muddledness and confusion that only a non-professional can do, which I need.

The film seems to embrace a lot of technical imperfections of this old technology.

A lot of rational people advised us not to do this, and said, “Why don’t you just shoot on the nice modern stuff and then we can put on filters in post that can recreate that look for you?” And we did some very half-assed experimentations with that, but I knew we didn’t want to do that. That would have been really contrary to the spirit of the whole project, as far as I was concerned. In taking on these cameras, of course we knew they were going to be imperfect. That was part of the point. And we knew they would give us headaches. Somehow that was part of the point, too. When it came time to edit, and I was looking at the footage, whenever I would see some kind of bizarre glitch I would get excited. If we had gone the contemporary high-tech route and tried to recreate this look in post, we never would have been able to come up with those glitches. It wouldn’t have occurred to us.

You edited your first three features on an old Steenbeck, this giant analogue machine that was once the way all movies were edited. What was it like editing digitally.

It’s funny, I tell people I edited three features on a Steenbeck, and they go “Ohhhh,” and step back. But for less about a hundred years, that was how every movie was cut, and there was nothing impressive about it. It’s kind of a frightening thing about the twentieth century: Things that were quite conventional and normal have come to seem too difficult for anyone to do. It made me a little sad. I still have the Steenbeck, but I would work every day with my back to it. [Laughs] Obviously there wasn’t an option to cut “Computer Chess” on a Steenbeck, because we were working with digital footage. But also it’s about computers so it made sense in a thematic way to edit on computers. And my life has changed considerably since the last time I did this. I’ve always been a slow editor. The computer picked up the pace on this one, but also me being a father slowed down the pace. It ended up taking as long as the last one to finish. Every editor I’ve ever talked to who survived that transition to digital talks about how different it feels and how it’s much harder to settle on anything, because you can move so fast. There is something about taping two pieces of film together that feels intentional in a way that a digital edit tends to feel a little more arbitrary, because you can undo it in twenty seconds and do something else. I better have a good reason to make the cut here, and if I change it I better have a good reason for that. You don’t need a good reason for anything on a computer. This movie in particular was so peculiar. There was no obvious movie I can think of that it’s supposed to move and think like. It was really hard to know when we were on the right track.

The film touches on lots of ideas from the past that haunt us today: Fear of computers taking over man, loss of communication, etc.

It was kind of a surprise me after we actually got into the actual making of the movie, to realize we were dealing with lots of themes and issues that were incredibly relevant to our times today. I’ve never made anything relevant before. I probably never will again.

What ideas did you want to explore?

I was a very small child in the era we’re depicting. But I remember those anxieties. I remember the excitement of computers and what they were going to do for us. I thought it would be very easy for us to look at what we were thinking back then and laugh at them, and think we were all wrong. We were worried about Terminators when no one was worrying about Facebook. But I felt to dismiss those philosophical questions of that time as quaint is to do a disservice to them. I think those were good philosophical questions, and I think they’re still relevant. I certainly don’t think they got answered. So I like the idea of going back to those and digging up those old questions and seeing what they could do for us today.

And yet it’s not a thesis film. You’re not just trying to prove a point.

If you make a movie that could be a paragraph instead, you can save yourself a lot of time and trouble by just writing that paragraph.

All your films tend to go against what is popular at the time. Are you conscious of that?

Certainly, that’s the dream. And maybe it’s my contrarian streak, but I hate the idea of going out and making something that somebody else down the street is making better. I can only get out of bed and work on something if I think is original — not because I’m brilliant, but because it’s mine, I’m the only one who’s going to make this. And if I don’t do this nobody else will.

Part of the budget for this was crowdsourced on USA Projects. But methods like that and Kickstarter don’t really solve everything, do they?

No, of course not. It’s helpful. But I don’t like it. I didn’t like doing it. I don’t love begging my aunt for a hundred bucks to make a movie. There’s also this: My greatest fantasy was to not tell anybody about it till we premiered it. And doing a Kickstarter campaign or a USA Projects as we did forces you to promote something you haven’t made yet. I don’t like promoting things when they’re done, let alone when I haven’t done them. Ultimately it’s like how many times can I do this? If I make another movie next year, am I going to knock on those same doors and say, “Now give me money again which you’ll never see back!” I’ve lost track of how much money I’ve given to others. Because people were so kind and generous with my project, I felt the moral obligation was to support people who came to me.

It can’t be easy to find money for films, even today.

I’m more worried about personal finances than I’ve ever been. I’m desperately trying to sell out. That’s not easy these days. I’ve never had a knack for it. I also know myself well enough that I’m always going to be itching to do something weird and crazy and commercially disastrous again.