The chief concern of “Parasite” is the class difference between two families. The Kims live in the low reaches of the city slum, each family member unemployed as they fend for scraps. The Parks live in a tasteful home on top of the hill and are comfortably wealthy: Mr. Park is the breadwinner and Mrs. Park is preoccupied with her young son and seems to not be the sharpest knife in the drawer.

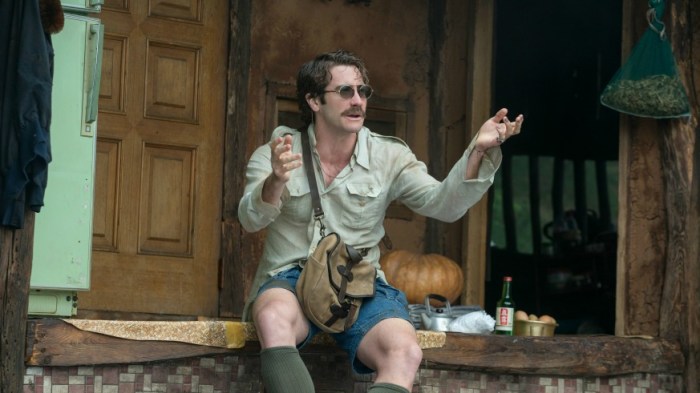

Keon-kyo (Yeo-jeong Jo) in Parasite. Courtesy of NEON + CJ Entertainment.

Their lives connect when the Kim’s college-aged son tells a white lie to get a job tutoring for the Parks’ teenaged daughter. As further deceptions, plots, false pretenses and outright frauds are committed, the entire Kim family has supplanted the preexisting service staff with false identities. The Parks are clueless that their entirely new servants are a family. But it’s only at the midway point when the Parks leave the house for a long weekend do the Kim’s receive an unexpected guest and a big surprise.

Audiences familiar with director Bong Joon-ho’s films (“Okja,” “Snowpiercer,” “The Host”) should have an expectation of the tone of “Parasite.” It contains elements of drama, action, suspense and — most deftly utilized here — black comedy. The Kims’ financial situation has forced their hand; they’re taking the best opportunity they can, as any capitalist purist would advocate. The Kims’ only degrees of morality apply to their own family. Their situation compels them to usurp the existing people relying on the Kims for their own money — people from their own financial stratum. The Parks are oblivious, myopically focused on their own situation (not unlike the Kims’) and sedated with the degrees of comfort. At times, they literally cannot perceive the activities of their service staff as they are right under their noses.

There are particular images and concepts within “Parasite” that afterwards remind you that underneath the service, things can have other meanings: a flashing light, a rock the space underneath a piece of furniture, or even just a peach can take on a different context. And it all implies the greater commentary the movie is offering: that our class predispositions orient and in large part dictate how we see the world, and that we can be utterly, wholly ignorant of things of great significance. We like to think that we can change our class or improve our footing in society, but that would imply we can inherently change who we are.

“Parasite” is at its best when it functions as a sleight of hand. It’s not to say the plot has misleading or story lines rife with misdirection. The sleight of hand works best when it becomes apparent that the themes at play are often not the themes we are seeing play out on-screen between the characters. The message is indirect, disarming and ambiguous. A lesser director or writer, likely an American towing to certain sensibilities, wouldn’t let the story of Parasite unfold or end the way it does. Anything even a touch more grandiose or bombastic would be a transparent, sentimental and a betrayal of the core truths of the characters and the story. Some things will not work out, no matter how much luck or effort comes into play.

At a certain point, an immense rainstorm hits the city. The slum becomes flooded. The Kims hadn’t locked up their basement squat, having recently spent so much time at the Park residence. Their neighborhood is devastated. The sewage water in their unit goes from their hips to their necks in short order. Their home is ruined and the toilet is spouting brown water. The forces of nature are relentless and have trickling effects beyond our senses. Joon-ho’s narrative deeply knows the cumulative effect that our daily conditions have on how we make our decisions. Each character’s decisions are relatable and understandable, whether it’s an outburst of violence or the effects of a series of slights and insults. The notion of free will feels minimized when seeing that sometimes there really is only one choice to be made. Seeing “Parasite” should be one of those.