“I do movies for personal reasons,” Édgar Ramírez tells us. Before he was in Hollywood movies, the Venezuelan actor was a journalist, and spent much of his life traveling the globe with his father, a soldier. He even considered becoming a diplomat. When he started appearing in films, like “Domino,” “Zero Dark Thirty,” “Joy” and especially “Carlos,” he always did so because he connected with them on a deep level. As such, he sees a lot in “The Girl in the Train,” the splashy film version of Paula Hawkins’ mega-bestseller about a lonely woman (Emily Blunt) who gets involved in the case of a missing woman (Haley Bennett). Ramírez, 39, only has a small role in the film: He plays the therapist to the AWOL girl, who becomes one of the possible suspects. But that doesn’t stop him from waxing on what it says about society, the dangers of technology and, of course, Trump. What was your big connection to “The Girl on the Train”? RELATED: Interview: Justin Theroux on “The Girl on the Train” and how acting “isn’t brain surgery” I’m old enough to remember that era. “The Girl on the Train” is a very empathetic portrayal of a troubled woman who’s been cast out of society — someone we’d probably ignore if we ran into her. Emily Blunt’s character is also prone to stalking and spying, which is something that technology has made easier. But I’d argue social media can create real connections, as well as fake ones. Right now, it’s a double-edged sword, because on one hand social media has been provably instrumental in helping, for example, revolutions in the Middle East. But it’s also awakened, in others, deep-seated prejudices and bigotry, and created the illusion of democracy. RELATED: Interview: Édgar Ramírez on “Joy” and how to be a male feminist We often joke about real problems, which can be therapeutic but can also run the danger of trivializing them. I love this country; this country has given me countless opportunities and embraced me and I love it. But the reality is the majesty of political debate is gone, maybe permanently. Because when you allow [someone like Trump] to happen, people start to copy that behavior. You become nastier and nastier and nastier, and then you can’t really talk. It’s no joke. It’s not wise to think these clowns are harmless, because they’re not. They’re not clowns, they’re not funny and they’re not harmless. When Trump announced his candidacy, we definitely treated it as a joke for far too long. We never thought it could happen.

It’s been a long time since Hollywood did a movie like this. We’ve seen strong and complex adult dramas in the independent world and overseas, but this movie reminds me of the great adult dramas from the ’80s and early ’90s: “Basic Instinct,” “Fatal Attraction” — films with messiness and complexity.

They were the movies our parents didn’t want us to see. You would watch it on Betamax. [Laughs] I’m very excited because I think Hollywood tells those stories very well. American cinema is fantastic. If this movie performs the way we expect, it could open the doors to these types of films coming back on a big scale. Then we have options other than horror films and superhero films. We’ll that collective experience of moviegoing.

The movie holds a mirror for us to recognize ourselves in the brokenness, so to speak, of the three main, female characters. That’s very refreshing. Because female complexity is so interesting to watch onscreen. We all deal with burdens and guilt and unfinished business. We all want to move on from something. We all want to detach from something that causes us pain.

I don’t see technology as a threat. First of all, it’s inevitable. I remember people being afraid of cellphones in the ’90s. I remember my first years of college, when some of my classmates bought phones, they were ostracized. They were laughed at and bullied. Then two years later everyone had a Nokia. For me, it’s nothing but resistance to change. Because it’s frightening — change is terrifying. You’re leaving your comfort zone. Where social media is going to take us has yet to be seen. We’re only seeing the beginning of it.

There’s this fake assumption that everything that is trending will necessarily have an impact and change things. When a social event is trending, the reality is: so are cats. It’s not access to technology that changes things; it’s how you use that technology. You still need to do the groundwork of getting your hands dirty to achieve change. Before social media when you knew about something, it was probably because progress was already happening. Now, knowing about something doesn’t necessarily mean progress is taking place.

That’s another problem: Everything’s becoming a joke. That is very dangerous, because that takes away from debate. It’s a strategy to distract. Everything’s becoming so infantile; everything’s supposed to be a joke. Everything’s supposed to be a soundbite or 140 characters, a meme. Those are fun; I send and receive memes and I laugh at them. But what’s going on here in the U.S. is not foreign to me at all. I come from Venezuela, and I’ve seen what’s happening here. I’ve seen how damaging populists, of any kind, of any ideology, can be, and the damage they inflict on society. What happens is you simplify everything so that they’re easier to manipulate. It’s very subversive, and not in a cool way.

The Germans said, “This could never happen here.” The Venezuelans said, “This could never happen here.” And look: it happens to everybody. I thought this populist seduction would only have an effect on less organizes and less institutionalized societies. But everyone’s susceptible to falling into this trap.

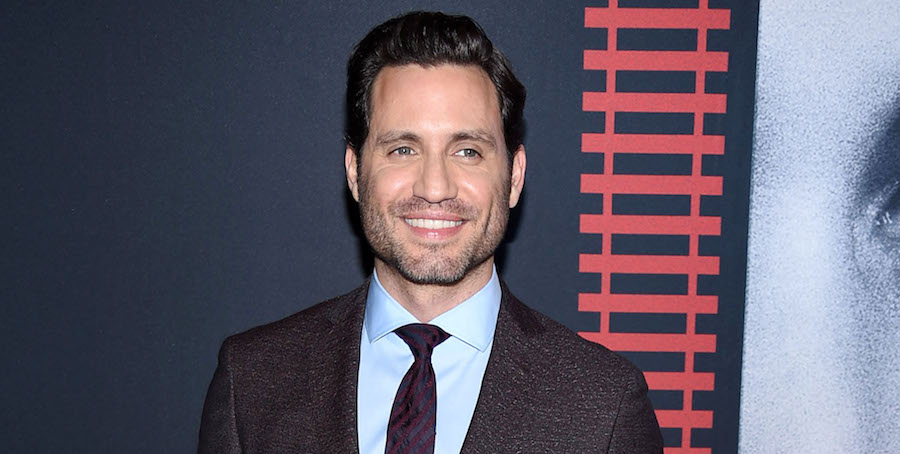

Édgar Ramírez says joking about Trump is dangerous

Getty Images

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge