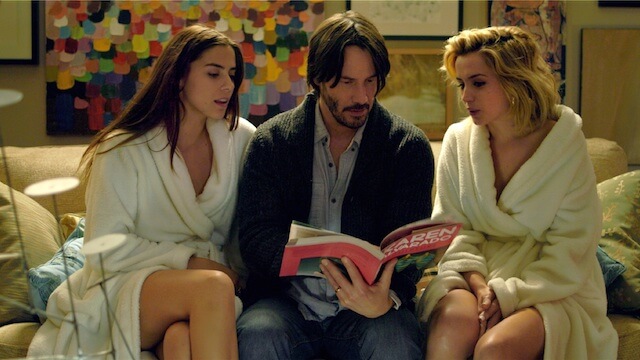

‘Knock Knock’ “Art does not exist,” reads graffiti scrawled one of the framed paintings adorning the Hollywood manse in Eli Roth’s “Knock Knock.” It’s a clear provocation, not only to bourgeois ideals but to the filmmaker’s many critics. Since “Cabin Fever” and especially with his two “Hostel” romps, Roth has fashioned himself on the extreme gore-masters of old, which means he’s inevitably been accused of bad taste and polluting the world with pornography. (“Hotel” helped birth the phrase “torture porn.”) But his work, as with the films of “Cannibal Holocaust” maven Rugero Deodato, is technically assured and has always been slyly satirical, even thoughtful — nuances that are often lost in the pursuit to eviscerate him for eviscerating his characters. “Knock Knock” exists in part as a rejoinder. Technically it’s a torture film. Thing is, there’s next to no blood and not a single dismemberment. It’s a psychological thriller that often feels, especially in its first stretch, like a play. Keanu Reeves is Evan, an architect left alone in his gated community home to work while the wife and kids are off on a beach trip. Right on cue, he finds himself opening the door to two young women — Genesis (Lorenza Izzo, Roth’s real-life wife) and Bel (Ana de Armas) — who need a phone, and a place to dry off during torrential downpour before hitting a party. Evan plays gracious host, and is careful to keep things cordial and, more important, non-lecherous, even as they start oohing and ahhing over his extensive vinyl collection, over his shaggy hair, over his wise maturity — over all the things that a one-time hellraiser who has settled into the placidness of middle age wants people, especially young, scantily-clothed, sexually open-minded females, to notice. Reeves himself hasn’t always been comfortable in front of the camera, but he’s chilled and relaxed as he’s gotten older. He makes one believe Evan only, or at least mostly, has pure thoughts about his slinky guests — right up to the moment when they force themselves on him and he finally and abruptly flip-flops. We probably also believe that he’s simply ill-equipped to deal with the morning after, when Genesis and Bel won’t leave, especially the more Evan turns hostile. Soon enough, they’ve knocked him out, tied him up and started messing with his head, and not just physically. They allude to previous victims of similar abuse, and are soon telling him that because of the previous night’s transgression, no matter if it was very close to mere entrapment, he must pay with his life. Roth and his screenwriters are careful about parceling out information and at making us wonder Genesis and Bel’s threats are for real or just a game. And they’re careful to present the situation clinically. We may feel for Evan, and he almost certainly doesn’t deserve severe punishments for a deed he truly had to be dragged into making. It’s as though Genesis and Bel are close to the pre-cogs from “Minority Report,” castigating him for even thinking of betraying his wife and kids. At the same time he’s not entirely blameless, and it becomes alternately horrifying and deeply satisfying watching them make a destructive mess of Evan’s moneyed home — tearing up his couches, breaking his records and busting up and graffiti-ing his artwork, including sculptures made by his wife due for a gallery in the morning. In fact, the second half of “Knock Knock” essentially turns into a (psychological) torture porn version of the great Czech New Wave classic “Daisies,” in which two young women play anarchists, gleefully laying waste to every facet of restrictive, bourgeois society. That’s what Genesis and Bel are doing. Their giddy, cackling massacre of Evan’s wares and his life ultimately have little to do with Evan himself than for what he stands — the type who settled for conformity, who acted against his instincts out of a sense of practicality, and who nonetheless wallows in permanent exasperation and self-hatred, all while convincing himself he’s hunky-dory. Genesis and Bel aren’t so much evil, heartless, easily distracted millenials as humanity’s carefree id sprung into manic action. “Art is not real” is not meant literally. It’s just another way to get a rise, to burn it all to the ground, and for an oft-maligned artist like Roth to make it clear that he knows what he’s doing.

Director: Eli Roth

Stars: Keanu Reeves, Lorenza Izzo, Ana de Armas

Rating: R

4 (out of 5) Globes

‘Knock Knock’ finds Eli Roth torturing Keanu, but not with knives

Lionsgate

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge