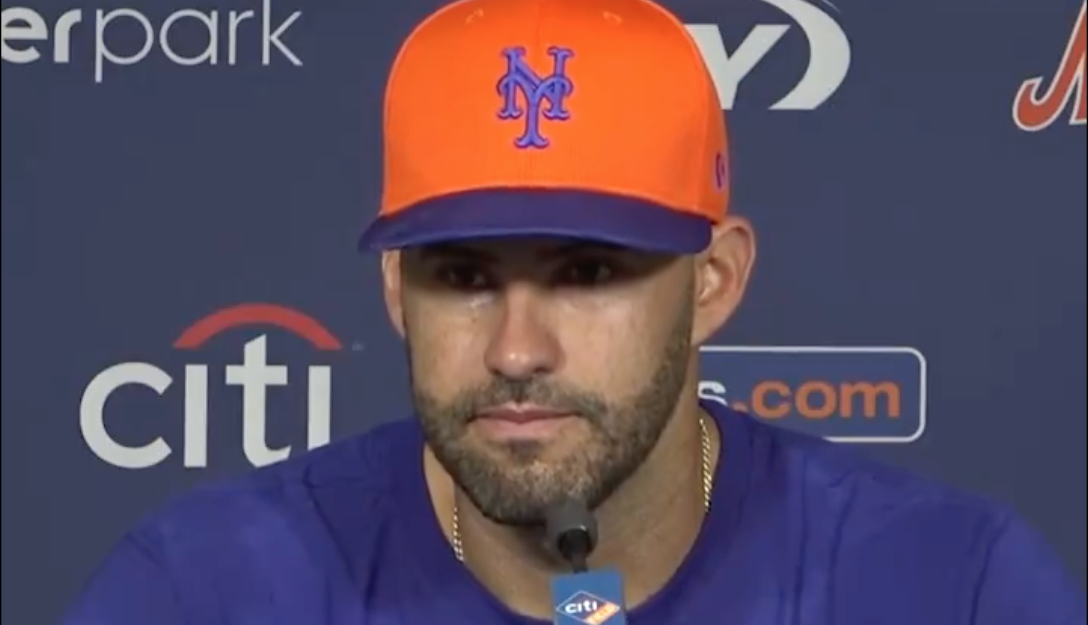

Willis Earl Beal plays a musician struggling to get it together in “Memphis.”

Willis Earl Beal plays a musician struggling to get it together in “Memphis.”

Credit: Chris Dapkins

‘Memphis’

Director: Tim Sutton

Stars: Willis Earl Beal, Constance Brantley

Rating: NR

4 (out of 5) Globes

Running a fleeting 75 minutes, “Memphis” is an out-and-proud mood piece, which is to say it’s an anti-narrative that slathers its minimal storyline over a series of disjointed (and almost always mesmerizing) scenes. But it does have a story; you just have to look for it. Real-life musician Willis Earl Beal plays a never-named, nomadic singer who saunters into the titular musical metropolis, his reputation following him. People talk of his god-given talent, as though he was the holy version of Robert Johnson. Some of his mystique comes from him: He tells people he considers himself “a wizard” the way people state their name. And you almost believe him.

But “Memphis” is really about the interplay between the mysterious and the painfully real. It’s a folk tale frequently brought back down to earth. Like the film itself, Beal’s troubadour doesn’t seem interested in keeping focused. Those recording sessions never get very far. He talks more about music than he plays it. There are numerous interview sessions — usually with people we can’t see, as though he was talking to himself — where he rambles freely but sometimes slips into a kind of abstract lucidity. It’s not clear, for example, what he’s referring to when he talks says, “Burn it down, just f—ing burn it down.” But you don’t need too many guesses to figure out what he’s talking about.

“Memphis” isn’t exactly unique; the festival circuit and art house theaters are clogged with experimental narratives that, as here, tend to unfold in carefully considered yet loose one-take long takes. Few of the ones here, designed by director Tim Sutton, are grandstanding; one that sticks out finds Beal recording, his face obscured by blaring blue and red lights. (It looks like a color version of Pedro Costa’s hypnotic “Ne Change Rien,” which showed actor-singer Jeanne Balibar performing in a series of black-and-white tableaux.)

But the scenes add up, each one blending the documentary (including scenes in Deep South churches, during apparent real services) with a minimal of fiction. Sutton follows Beal as he suffers endless distractions: from friends, from lovers, from his own temptations and vices, from his own lack of money. He’s such a mysterious figure that even he can’t figure himself out. “Memphis” is really about something, and something unique: It considers how greatness manifests itself, how it emerges from the head and into the world, how we do our ideas. It rarely articulates this in dialogue; every frame of it embodies it. It’s a heartbreaking look at literally staggering genius.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge