‘The B-Side: Elsa Dorfman’s Portrait Photography’

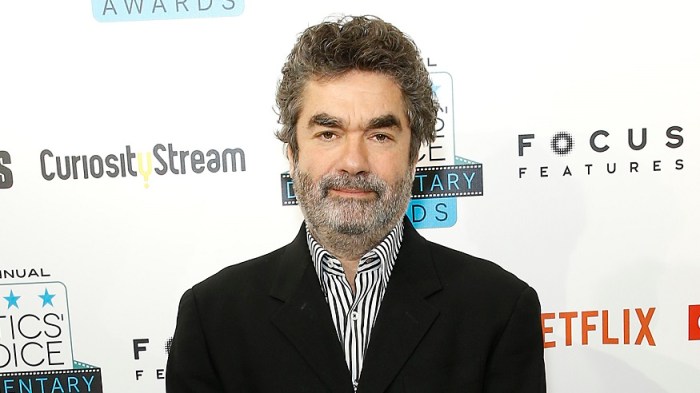

Director: Errol Morris

Genre: Documentary

Rating: R

4 (out of 5) Globes

When Elsa Dorfman holds up one of her countless photos in Errol Morris’ “The B-Side,” she sheepishly holds it in front of her face, eyes peering over the top like Kilroy. The stars of Morris’ documentaries tend to have something to hide. They’re murderers who’ve yet to confess (“The Thin Blue Line”), sociopathic pols who don’t think they’ve ruined the world (Robert McNamara in “The Fog of War,” Donald Rumsfeld in “The Unknown Known”). Morris gets them comfortable, has them stare into his Interrotron camera and out — sometimes, in some effect — come the secrets.

Dorfman has nothing to hide. She’s a touch shy (see the lede), but she’s usually giggly and gabby. She’s never done anyone wrong. She’s a “good Jewish girl” who takes portraits — large, vertical photos snapped with her instant Polaroid camera, meaning her worst sin is a botched snapshot. Her career spans back to the late ’50s, and her collection includes a mix of anonymous clients and a who’s who of artists and intellectuals, including Jorge Luis Borges, Anais Nin, Audre Lorde and Allen Ginsberg, one of her closest friends and most frequent subjects.

Whether Dorfman is the nicest person Morris has ever subjected to a film-length interview is up for debate. There are the oddballs of “Gates of Heaven” and “Fast, Cheap & Out of Control.” But Morris still tries to coax something out of the decent ones, too — ideas they don’t realize they’re spouting, which he then structures into one of his dizzying film essays.

Not so much with Dorfman. In her, Morris sees more of a kindred spirit. Her tool is a camera, too. Her Polaroid camera even faintly resembles his Interrotron. They’ve both trained their lenses on the famous and unknown alike, and both seem to agree that turning a camera on someone both reveals some truths and fails to get others. In its cagey way, “The B-Sides” is a kind of stealth semi-autobiography, Morris using Dorfman to reveal his own obsessions and theories.

Even when their lives differ, you can see some semblance of truth. “The B-Sides” exists in part because Dorfman had retired. Polaroid was taken over by “idiots,” as the usually menschy Dorfman puts it, who canceled their instant film stock, basically putting her out of business. Dorfman adores the look of film — the textures, the special-ness, the imperfections.

She says this into a digital camera. Morris was cool making the switch to celluloid, but through Dorfman’s many odes to film, you can suss out a bit of self-hatred — regret over not throwing in the towel out of protest like she did. At one point, she holds up an old photo that is so delicate it has a tiny crack on the back side. She asks if Morris’ camera can pick it up. Morris zooms in to reveal he can’t. (Or at least it didn’t on our online screener copy of “The B-Side,” which is a whole other discussion.)

Morris’ films are gorgeous and aggressively visual, but they’re never about what’s on the surface. He’s sneaky. Why does he shoot a film about someone who takes tall, vertical photos in rectangular widescreen, thereby often cutting off their tops and/or bottoms? Our theory is he wants to subliminally stress the fact that they’re now a dead art form. To put them in a film, even for posterity’s sake, would be to steal part of their essence. You’d have to visit Dorfman or go to a gallery retrospective to see them.

Dorfman never says this, nor does she say anything particularly dark. She hates that stuff anyway, and hates taking pictures of people who are “sad.” Still, “The B-Sides” is, in its quiet, charming way, a sad, dark Errol Morris movie, about loss and change and aging out of one’s profession. At one point, Morris, offscreen as always, is heard asking her about the “perishability” of her photos. She pauses, suddenly ashen, gives him a time-killing “Right,” then admits, “I try to deny it.” She’d rather not go there, and try as she might to keep things light, Morris has a way of sneaking some darkness in there anyway. He’s cunning, that Errol.

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge