Two years ago, legendary filmmaker Paul Schrader and Nicolas Cage teamed up for the thriller “The Dying of the Light.” It was a disaster. The film was taken away from Schrader in post-production by meddling producers, who released a cut no one involved liked, least of all its filmmaker. So Schrader and Cage decided to try again. The unexpected result is “Dog Eat Dog,” a wild, pitch black crime comedy about a group of thieves whose latest scheme leads to their downfall. There’s nothing on Schrader’s CV remotely like it: Movies like “American Gigolo,” “Affliction” and “The Canyons” are more studied, heavy, anguished — very much the work of someone who’s written a book on Yasujiro Ozu. (That’s to say nothing of his scripts for “Taxi Driver” and “The Last Temptation of Christ.”) “Dog Eat Dog,” based on a novel by Eddie Bunker, is in-your-face and unhinged, right from an opening scene in which Schrader regular Willem Dafoe whimsically murders two people — a set piece, mind you, played for laughs. This is a very different film for you. “Blue Collar” is funny and “Auto Focus” has funny parts in it, but you’ve never done a film that veers this far into pitch black comedy. RELATED: Interview: A fun chat with “Doctor Strange” villain Mads Mikkelsen about death Was it always supposed to be a dark comedy? It’s a worthwhile question. Today’s crime films can’t ape Tarantino, meaning you might have to start from scratch. You’ve said you made this as “redemption” for “The Dying of the Light.” Apart from your “Exorcist” prequel, which was entirely re-shot by another filmmaker, have you found yourself in similar situations going back through the years? I was wondering if you could talk about working with Nicolas Cage, who always appears like the kind of actor who will always surprise you, who will do the unexpected… Was the Bogart impression he does at the end something he came up with, or was that always in the script?

I don’t think I’ve ever made a film like this. I kind of wish I had pushed “Auto Focus” a little further like this. When I was editing this film, I felt with “Auto Focus” that it wasn’t clear enough to the audience that they shouldn’t take those guys seriously. So I wanted to make sure on this one it was very clear to the audience that if you’re taking this seriously, you’re in the wrong theater.

Neither the novel nor the script were a comedy. That dawned on us as we were working on it. I was doing a little bit of rewriting, I was thinking about it. I realized, ‘These guys are funny.’ Or they’re not funny, but the situation is funny, and they’re dumb. And it kept drifting more and more that way. I’m not a crime film director. I got involved in this to do another film with Nic [Cage] and gain a measure of redemption. It just so happened that the vehicle was a crime film. I thought of myself as being in an interesting position, where I had to figure out, at the age of 70, what a crime film looks like in 2016. This is what I came up with.

So much of crime and police dramas are built on patterns you can enjoy repeatedly. Instead of that, I wanted to create a kind of jazz solo that riffs around and you don’t know where it’s going. It’s fun to not know where you’re going.

I never really felt the need in the past to have final cut. I always worked with people who respected movies and liked movies. Of course there would be a heated discussion with the studio about what’s the best thing for the movie. But you would always come to an agreement. In the last 10 years or so, we’ve seen money coming into the movies from people who neither watch nor like movies. When you find yourself in a room with this kind of money, you have to push to find a way to protect yourself.

That’s what he wants you to believe. He is not that way. He is very well-prepared, very, very calculated. He wants you to think he’s irresponsible. But he’s among the most responsible actors I’ve ever worked with.

That evolved when we were shooting it. It was not in the script. He was basing his character on a guy who liked Bogie. I didn’t care much for that, but I was alright with it. I thought I could cut it out. Things came to a head when we kept talking about the final scene. He said, “I don’t know how to play it. I don’t know why he’s alive. I don’t know what he’s doing with that black couple.” I said, “Maybe he isn’t alive. Maybe this is an afterlife sequence.” That’s when we got the idea that if it’s an afterlife sequence, he could be Humphrey Bogart. [His character] always wanted to be Humphrey Bogart, so he became Humphrey Bogart in the afterlife and saves the black couple. Of course, he f—s that up, too. [Laughs]

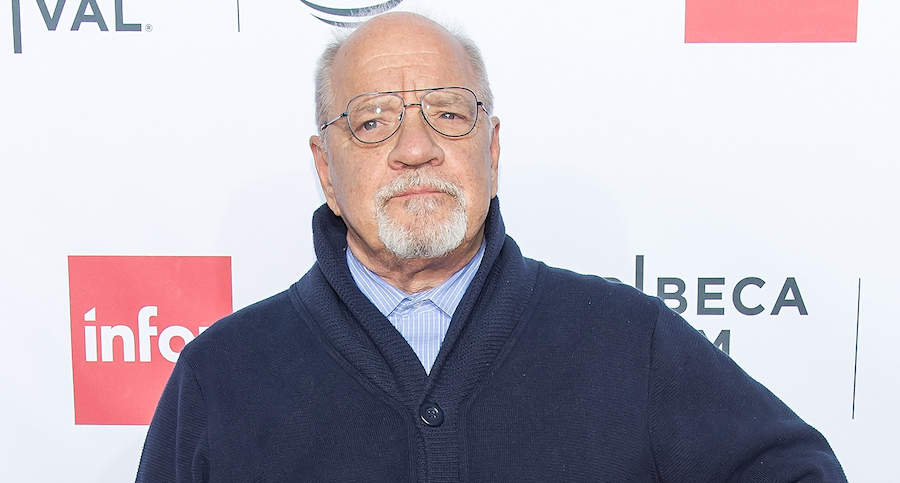

Paul Schrader on ‘Dog Eat Dog’ and Nicolas Cage not being that crazy

Getty Images

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge