The Beatles are usually in motion in “A Hard Day’s Night.”

The Beatles are usually in motion in “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Credit: Bruce and Martha Karsh

On July 6, 1964, a low-budget, black-and-white English musical made on the quick — because it was assumed its stars were a waning fad — hit United Kingdom screens. “A Hard Day’s Night” was assumed to be another “jukebox musical,” the term for the frivolous, quickie movies hot bands had been forced to do since the mid-’50s.

But its stars, The Beatles, didn’t want it that way. The band teamed with United Artists, the studio legendary for granting filmmakers artistic freedom (and for their Anglophilia — at the time they were on their third James Bond movie). They hired as director Richard Lester, whose work to that point had been in television, comedy and music. As it turned out, a movie that was bound to make money anyway became beloved, even influential, as well.

“A Hard Day’s Night” is being reissued, in select theaters and on disc, for the 50th anniversary of its original release. (Although it didn’t reach American shores till August of 1964.) It’s been dusted off before, notably in 1982, when it was fitted with a photo montage prologue that murdered the most electric opening moment in film history. On the souped-up Criterion Collection set that just came out, the opening doesn’t even have a production company credit. It’s right into the first chord and the sight of the Fab Four hurtling towards the camera, which plays, as always, like a shot to the gut.

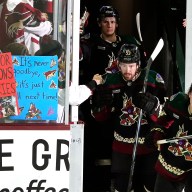

John Lennon was actually away at an awards ceremony during some of the filming of the “Can’t Buy Me Love” sequence.

John Lennon was actually away at an awards ceremony during some of the filming of the “Can’t Buy Me Love” sequence.

Credit: Bruce and Martha Karsh

A slapdash production

Time was instantly kind to “A Hard Day’s Night,” though the haphazard nature of its production can’t be stressed enough. The budget was actually less than that of “Please Please Me,” the band’s first album. Lester and screenwriter Alun Owen had untold restrictions: don’t focus on their drinking or marijuana intake, don’t talk about their craft and nothing personal. Moreover, the Beatles were novice actors, meaning the dialogue had to be whittled down to one-liners and jokes — things they wouldn’t forget or screw up.

Lester was a television vet and he brought speed, economy and quickie problem-solving to bear on the film. (That it was also largely based around a television production surely made him feel at home.) The famed scene where The Beatles feed nonsense answers to hungry journalists was thrown together at the last second, after one scene was mobbed by fans..

Lester’s yen for handheld camera and fast cuts not only created high energy. It also smoothed over production hiccups. When John Lennon had to go accept an award for his wordplay-heavy book “In His Own Write” while the others filmed the “Can’t Buy Me Love” sequence, he improvised, then diced it up so that you barely notice when he’s not there. Lester even busted out innovative shots with nothing much at all. The graceful pan around Paul McCartney as he sings “And I Love Her” — complete with lens flare, which was a no-no in 1964 — was done with the camera operator sitting on a child’s swing.

The borderline slapdash way “A Hard Day’s Night” was made is also the reason for its brilliance and longevity. Without the grit, the resourcefulness, the speed, it might have actually felt like another jukebox musical. After all, it probably has LESS plot than most of the genre’s lot, which were already narratively gaunt. Indeed, it can look like all bluster, all youthful energy. The Beatles’ first film was instantly admired, but even some of its ivory tower admirers doubted its subjects’ longevity. Critic Andrew Sarris, in the Village Voice, famously dubbed it “the ‘Citizen Kane’ of jukebox musicals,” but noted the band “may not be worth a paragraph in six months.”

Paul, George and John, at least, had been bandmates since 1958, so they were hardly novices by 1964.

Paul, George and John, at least, had been bandmates since 1958, so they were hardly novices by 1964.

Credit: Bruce and Martha Karsh

Not novices but experienced artists

But they were worth a paragraph, several billion more, and the film shows you why. For one thing, though most involved were at least relative movie newbies, they were all old hats. Even the musicians weren’t new: John, Paul and George had been bandmates since 1958, and as historian Mark Lewisohn points out on a mini-doc on the film’s Criterion set, that meant they were halfway through their 13-year stint together. They had worked their butts off in both Liverpool and, most intensely, Hamburg’s red-light district, where they would play six-hour days, and were intent on not repeating songs. The Beatles had come a long way from sweaty rockers hopped up on the later-outlawed energy drug Preludin to lads who wore suits but also shaggy, trendy haircuts stolen from their former German home.

Lester meanwhile was on his third feature, though this was the first to truly combine his talents into one package. He had directed TV shows for the members of The Goon Show, working with comedy anarchists like Peter Sellers and Spike Milligan to create screen comedy. And this was in addition to spending years working on news programs, filling hours of time with sights grabbed on the sly. “A Hard Day’s Night” was the culmination of extensive teeth-cutting and dues-paying.

The pairing of Lester and the Beatles complimented eachother, fitting together like a key and a lock. The Fab Four wanted Lester for the job primarily because of “The Running, Jumping and Standing Still Film,” the absurdist 11-minute amateur short Lester had made over two weekends with the Goon Show cast, which had been nominated for an Oscar in 1960. While they shared his sense of humor, he had a musical background, both as a (by his accounts) terrible musician and with his debut feature, the music film “It’s Trad, Dad!,” in which Lester took what could have been a hackish musical revue and busied himself with visual and editing experiments he would carry over to “A Hard Day’s Night.”

It’s hard finding sounds and images that go together as perfectly as the ones in “A Hard Day’s Night.” Lester’s hurried, chaotic visuals — sometimes quick cuts of out-of-focus frenzy — matched the songs’ energy, be it the thrilled anxiety of “A Hard Day’s Night” or the somber reserve of “If I Fell.” It looked new. In fact, it looked almost too new: As United Artists exec David V. Picker has said, after he screened it to an audience of Old Hollywood types, one exec turned to him and said he had no idea what he just saw. But, he told him, “We’re going to make a lot of money, aren’t we?”

Shooting on a train going back and forth from London to Liverpool was one of many production headaches on “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Shooting on a train going back and forth from London to Liverpool was one of many production headaches on “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Credit: Bruce and Martha Karsh

Euphoria bottled up

“A Hard Day’s Night” has long been held up for uncannily bottling up euphoria, but it’s a euphoria that’s beside despair. As prep, screenwriter Alun Owen hung with The Beatles, and found pretty much what he showed in the film. They were rushed from place to place, usually in uninspiring rooms, living off room service, anxious for the kind of release they would get in the film’s open-air “Can’t Buy Me Love” sequence (where even as they’re running about, they’re being filmed from a helicopter). They were, as Owen often put it, “prisoners of their own success.”

Thing is, they’re too young, too boisterous to be down. Owen said they would only find cheer when they were playing music. But in the film they’re constantly subsisting on their own prankish, quipping nature, always getting the upper hand in unpleasant situations. They triumph over snooty elders, like the man on the train. (Him: “I fought the war for your sort.” Ringo: “Bet you’re sorry you won.”) They triumph over supercilious ad men (Kenneth Haigh), preening television directors (Vincent Spinetti) and, ultimately, over Paul’s grandfather (Wilfrid Brambell), who does his best to play bored saboteur, to the show and the film.

Thing is, the Beatles of “A Hard Day’s Night” would disappear, as Sarris postulated. The band of even the next album, “Beatles for Sale,” are very different from the cocksure if slighlty nervous band of “A Hard Day’s Night” — gloomier, more depressed, reflecting on failed love, even announcing that they wanted to leave the party. “Help!,” their cinematic follow-up from the following year, finds them even more detached, less boisterous, mostly reciting the (very, very funny and absurdist) lines Lester and screenwriter Charles Wood — a far sillier man than Owen, with a love of wordplay to match Lennon’s — gave hem.

“Help!” is traditionally criticized for not being another “A Hard Day’s Night,” but it’s its own thing, and in some ways superior. (Some of us actually enjoy revisiting it more, as we elaborated upon here; instead of inspiring MTV, it inspired Monty Python.) And you can’t recreate “A Hard Day’s Night.” It’s a flash-in-the-pan effort, succeeding because of low expectations and ramshackle conditions and because it starred a band that were on the cusp of getting fed up with the lifestyle they had achieved through their hard work. You watch it as a time capsule, as proof that there was ever a moment in time when everyone was this carefree, even in the face of the change and misery on the horizon.

Wilfrid Brambell (choking Ringo) was plenty famous himself, at least in England.

Wilfrid Brambell (choking Ringo) was plenty famous himself, at least in England.

Credit: Bruce and Martha Karsh

Miscellany to impress others at dinner parties

Richard Lester hated Wilfrid Brambell’s grandfather role and did his best to cut his presence down. But to English audiences, Brambell was only slightly less famous than the Beatles. He was the father on “Steptoe and Son,” the show that begat “Sanford and Son.” The running gag that has him repeatedly called “clean” was a reference to the show, where he was called a “dirty old man.” To its American audiences, and those today, it just seems another of the film’s routine nonsequiturs.

George Martin, the band’s storied producer, was nominated for an Oscar for his score. Together he only wrote 47 seconds of music. It’s regularly understood that the Academy meant to honor The Beatles but did it wrong.

The film is heavy on slang, and screenwriter Alun Owen even invented his own: “grotty,” short for grotesque. It’s now in the Dictionary.

While The Beatles changed and grew out their hair, Lester continued making even more inventive comedies, including his next picture, the breathless Swinging London satire “The Knack,” which won the Palme d’Or. But by 1967’s “How I Won the War” — which featured Lennon in a major supporting role — his comedy had turned sour, alienating, if still brilliant. In fact, many of his films are masterworks — like “Petulia,” “Juggernaut” and “Robin and Marian” — that marry comedy to a darker, detached view of humanity at its silliest and most self-destructive. Even his slapstick swashbucklers — the 1970s’ “The Three Musketeers” films — thrill at knocking heroes down to earth. He retired early, not long after lording over tow of the 1980s “Superman” sequels, and he’s modest to a fault. Asked in 1977 if he understood “A Hard Day’s Night”‘s acclaim, he said, “No. I still don’t and I think it a bit silly.” Still, when asked which film he’d leave to be remembered for, he picked “A Hard Day’s Night.”

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge