When Gianfranco started making “Fire at Sea,” no one was talking about the migrant crisis. Now that the film is out, it’s all they can talk about. The Italian filmmaker’s new documentary isn’t an activist film, and it tells you very little about what’s become a hot-button issue. In fact, it’s not even the main focus. The film — which won the Golden Bear at the Berlin International Film Festival and is Italy’s submission for the Best Foreign Language Film Oscar — was shot on the tiny Mediterranean island of Lampedusa which, over the last few years, has seen an alarming number of migrants passing through it en route to Europe. Rosi, though, was initially drawn to the people who lived on the island, especially after border officials began rescuing boats offshore, meaning there was little to no interaction between the locals and those passing through. The film shows parts of these rescue missions, including one unspeakably harrowing encounter at the end. But most of it is about Samuele, an 11-year-old local who knows nothing about the migrant crisis, and spends his days idling around, goofing off, shooting slingshots, being a kid. Rosi talks to us about how his acclaimed film has no thesis, getting his young star to ignore the camera and what it’s like to film death. RELATED: Review: “Fire at Sea” is more a portrait than an issue film about the migrant crisis This film has been addressed as though it were an issue film, but the migrant crisis plays a very small part in the overall structure. You cut between the people of Lampedusa and certain rescue missions, but apart from the doctor character, we never see them together. And you don’t explain why there’s a slim chance they’d ever interact. When you met Samuele, what prompted you to make him the main center of your film? What do they say? Was it tricky getting Samuele used to being filmed by a camera? Has he seen the film yet? What did he think? There are many minimalist documentaries like the ones you make, but they’re not the ones most people see. The documentaries most people watch tend to be expository or about highlighting key issues. They’re like a form of journalism. All this said, the end result is to make people aware of something they don’t know much about, to get them to do more research, maybe even become involved. Tell me about adjusting from shooting Samuele to shooting the scenes on the rescue boats, especially the one in which a large number of people have died. You had to film death. When you have that footage, how difficult was it to find a place in the film that wouldn’t cheapen it?

If this film came out two or three years ago, nobody would have talked about the migrants. They’d say, “Why the f— are there people coming from Africa?” Two years ago nobody talked about it. Everybody started talking about it when the Balkan area was opened up and thousands of people discovered this route to Europe. Europe suddenly became aware of this. When I was almost finishing the film was when it became this huge issue all over the news, all over the world. Before that, 500,000 people passed through Lampedusa in the span of a few years, and nobody talked about it, except when people died or a terrorist was found passing through Lampedusa. They forget that the terrorists are already in our cities. In France, the people who blow themselves up are third generation, not people coming from Africa or Syria. Trump was saying, “When people arrive, we don’t know who they are.” These people are from Syria.

Some people ask me why Samuele never meets a migrant. It’s because he didn’t. It was not part of his life. It would be completely fake for me to force him in that direction. I wanted to create a point of view that was more about being inside this world, with these people, having a feeling of what goes on around that.

When I met him I fell in love completely. He was very small, even for his age, but he had the head of an old man. [Laughs] He was like a young Woody Allen. He had a funny, clumsy approach to life. Everything’s against him: the lazy eye, the anxiety. He said he was a hunter but lives on an island. He hated the sea. There were all these contradictions in his life. At the beginning of the film he kills a bird; at the end he talks to a bird. I wanted it to be secret what they’re sharing; I didn’t want people to hear what he says. I wanted people to think, ‘What is that secret?’ When I show the film to kids in schools, I ask them to write me a page about what they think the conversation is between Samuele and the bird. And it’s fantastic.

One girl said the bird is telling Samuele to not be afraid of the unknown, to have the courage to meet something he was hunting. And the bird says, “Don’t’ be afraid of what you don’t know.” It was very beautiful. Somehow the metaphor for the migrants was the bird. The bird was a survivor from the sea. For me, this is a clue to unlocking the film, this moment where you don’t hear what they’re saying. You have to fill it in yourself and find the emotion that is there.

[Chuckles] Yeah, it was very funny. When we started shooting he was playing with this other kid. I turned on the camera and the two became cocky, really performing, looking at me constantly. It was horrible. I thought, ‘I cannot do this.’ One day I tried to film them again. They were fighting, they kept talking to me. So I just took the camera, packed and left. They were like, “What’s going on?” I said, “You bore me to death. I’m going home.” And I left. I ran into him a few days later and he said, “You won’t film us?” I said, “No, I’ll find some other kids. You were cocky and pretending. I’m not interested in that. I want you to be yourself.” He said, “Can you give us another chance?” I said, “No. I’ll find two other kids.” [Laughs] For two weeks I didn’t see him. Then he found me and said, “Please, I want to be in the film!” And when I tried again, it was magic. He completely forgot about the camera.

He saw the film at the Berlin Film Festival. At the beginning he hated me: “I can’t believe you put this in! I don’t spaghetti like that anymore! You showed me vomiting!” [Laughs] But he loved the film, he’s very proud of it. I’ve protected him from journalists. I don’t want him to give interviews. I want him to go back to his life and be the great kid he is. But the great thing is he’d never been in a cinema in his life. So he’s in Berlin, 1500 people, one of the best cinemas in the world, on the biggest screen ever. He saw himself onscreen during his first movie. It was very emotional for him.

They’re very informational. There’s always a thesis. My film has no thesis. My film probably asks more questions than it has answers. But we live in a world where we have so many answers. Just Google it. You have information on everything. There was a fantastic article in the New York Times Magazine about the Middle East; that’s a good example of journalism. But I think cinema has to use a different language for that. And for me, documentary is cinema. The beauty of documentaries is they constantly challenge you to find a new language. Every film I do is a challenge to find a new language to tell the story. When I tell a story, I go there with nothing — maybe a little idea that is small enough to be contained in a pack of cigarettes. If it’s bigger than that, it’s wrong. I build my film around that. Making a film is like a labyrinth where I have to find an exit. It’s a journey for me.

The whole world should be coming together to ask, “What should we do?” We should open up [borders]. We cannot leave the people in Libya in the hands of human traffickers. [Migrants] pay money. The boat in my film has 600 people; each person pays $1500. There’s almost $900,000 on that boat. A few weeks ago, in one day, 7,000 people were saved on the sea. Imagine 7,000 by $1500; that’s however many millions every day. That’s better than arms or drugs. It’s a business in the hands of criminals in Libya. The migrants are facing death in the sea. 25,000 people died [during migration] in the last 15 years. The Mediterranean is like a cemetery — like a profound tomb.

When I shot, death came to me. It was on one of the rescues; I did so many. I spent 40 days on the military boat. And one day I met death. It came to me. I had a split second to ask myself, ‘Do I film or not film this? What do I do?’ I decided in that moment this had to be brought to people’s awareness. When I went down into the ship to film, it was the most horrific scene I ever saw in my life — these piles of bodies embracing each other in this last sigh of life. These people suffocated on the fumes of the engine under the boat. It was like a gas chamber. It was like an execution. When I filmed that, all my energy broke to keep making the film. I said, “I have to start editing. I no longer have the energy to film.” Filming death is something that changes you forever.

Deciding to put that in the film was a challenge. I said to my editor, “I want to use these 30 seconds. But the whole film has to build to this moment.” I said, “We have to conquer this moment. If we don’t, we don’t put it in the film.” I had a structure to arrive here, to show death. But then I realized I couldn’t end it there; this could not be the end of the movie. I had to give dignity to all the people — Samuele, the doctor, the mother — who accompanied me to this moment. So the last part of the film is silence; it’s mourning death. The whole film was built to show these 30 seconds, but to not make it exploitive, not make it pornographic. It’s really hard to show death. I wanted the film to make people accept death as a tragedy then ask, “What can I do?”

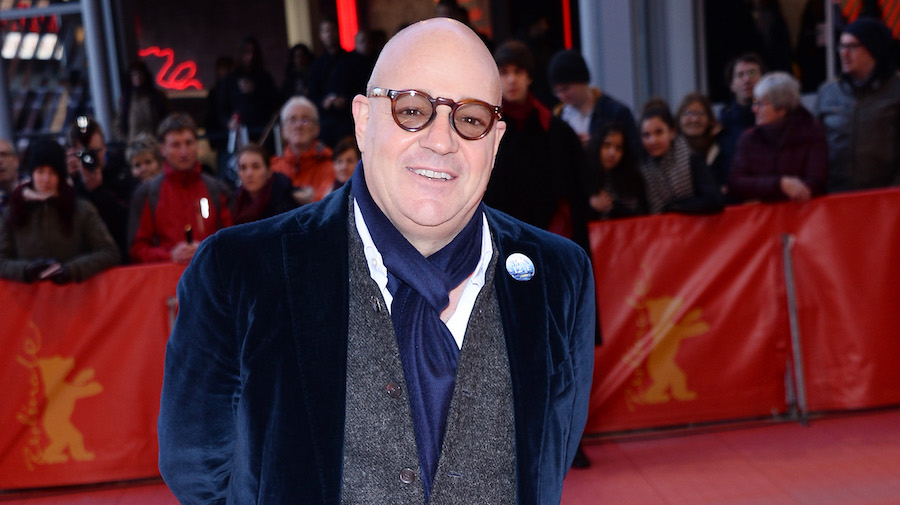

Gianfranco Rosi on ‘Fire at Sea,’ the migrant crisis and filming death

Getty Images

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter @mattprigge