“National Gallery” is the 41st movie Frederick Wiseman has made in 47 years of filmmaking, and in a sense it’s more of the same: Like “Titicut Follies,” “Hospital,” “La Danse,” “Crazy Horse” and more, it’s a purely observational exploration of an institution with no narration or music, which conveys its ideas and themes purely through which things he chose to show. Not that every film is the same. This is one of his long ones, running just over three hours. (That’s not his longest, which would be the six-hour “Near Death.”) Wiseman filmed it over three months and edited it over 13 months — impressive both because of the prolific nature of his work (the four-hour “At Berkeley” only came out last year) and because of his age. He’s a spry, eloquent 84, and it’s only because he keeps in shape that he’s able to keep on his feet. With the release of “National Gallery,” Wiseman discusses how his methods have stayed the same, how they’ve changed and that time he found himself on the set of “Tootsie.” Like most of your films, you didn’t know much about how museums work before you started this, correct?

In one sense each film is a report on what I’ve learned. I hope it’s more than that, but it’s certainly that.

Do you tend to pick subjects because you want to know more about them?

Well, no, but the fact of the matter is with most of them I don’t know much about them in advance. I’ve never lived in a public housing project. I’ve never been a policeman. I’ve never been arrested — though I’ve gotten a lot of speeding tickets. I’ve never been on welfare. I’ve never danced. Speaking of which, one of the final scenes in this is a dance in front of paintings.

That was great luck. When I got to the National Gallery, one of the curators told me they and the Royal Ballet had commissioned three ballets based on themes from Titian paintings. And for one of them the chorographer was Wayne McGregor, who was in “La Danse.” He was going to rehearse his dancers in front of the Titian paintings. So I called him up and asked if I could shoot while he researched, and he said yeah. Did the National Gallery impose any restrictions on what you could shoot?

No. The only thing I couldn’t shoot was the executive committee meetings if they were discussing personnel problems, but that’s fair enough. Other than that, I could go wherever he wanted whenever I wanted. I had a little badge that allowed me to get through the security systems and doors. How often would you shoot?

Most of the time you’re making one of these movies you’re not shooting. I was at the National Gallery 10 to 15 hours a day sometimes. And the most I’d shoot would be two hours. The rest of the time I used to educate myself about what’s going on. Either I was wandering around or talking to people. Were there special challenges with “National Gallery” versus your other movies?

The most interesting thing was finding a way of shooting the paintings. I decided early on the best way was to shoot inside the frames, so the paintings filled the frames of the movie. Otherwise the painting would become an object hanging on the wall and you were distant from it. If you were inside the frame it became much more vivid and alive and vibrant and all those other words. And you can shoot the painting serially, in the sense that you could go in tight and show parts of the painting. You could tell the story of the painting in a series of shots rather that in one shot. In that way it came close to being film or other forms of storytelling. You are famous for staying unobtrusive. How often do people look in the camera? Has anyone ever done that while you were in the middle of something great?

No. And I’ve been doing this for a long time.

There’s that cliche that when people know there’s a camera on them, they act up.

If people were acting for the camera, there’d be this great field of blandness, because then people wouldn’t take risks. What’s true of people in the films is true of all of us: We don’t see ourselves the way other people see us. We think what we do is OK. But someone else looking at it us may have a different evaluation. They may think we either show great kindness or more cruelty than we think we do. You tend to film people giving their legal permission to be filmed rather than have them sign a form. That sounds burdensome when filming in a large public space like a museum.

There was a sign posted to all of the entrances that said “Filming in progress today. If you don’t want to be filmed, please tell the film crew.” And nobody ever did. That way everyone was notified, and were given the chance to let us know if they didn’t want to be filmed. It was much easier. You’ve directed one fiction in your career, “The Last Letter.” Could you imagine doing another?

No. I like doing the documentaries, because it’s fun. You don’t have to do the same take 20 times. A number of years ago, a photographer I knew invited me to the set of “Tootsie.” There was a crew of 200 setting up a shot of Dustin Hoffman talking to somebody else. I doubt very much the quality was any better than what you do with a small documentary crew. That style of filmmaking has always seemed laborious.

It’s boring!

You prefer to call your films “films” not “documentaries.” Do you even view them that differently from narrative films?

Many of the issues are exactly the same. With documentaries you still have to work out a dramatic structure. You do it a different way, but it’s still a movie. Years ago the word documentary was almost like a prescription. It was good for you. You needed it for moral or intellectual education. But documentaries can be as funny, as sad, as tragic, as moving as good fiction films. Some people think documentaries are reality captured unvarnished.

That’s bulls—.

You’ve said you don’t know what movie you have until you’re in the editing room, but are you often piecing a film together even as you’re shooting?

Yeah. For instance, with “At Berkeley” there were a lot of administrative meetings. I know from past experience I’m going to need a lot of cutaways to edit it into a usable form. If the meeting is 90 minutes, I know even before the meeting starts that it’s unlikely I’m going to use more than 10 or 12, if that. I know that I’m going to need cutaways of people listening, watching, writing on their pads or whatever. That’s what’s called learning from experience. Sounds like it could be pretty boring to sit through an entire 90-minute meeting.

Oh sure, sometimes it’s boring. But my general rule is even if it’s boring, if you’ve made up your mind that you want to shoot the meeting you do it. There’s only one rule in this kind of filmmaking: You can never accurately anticipate what anyone’s going to say or do. I shoot the whole meeting because if I stop, the very moment I stop the most interesting thing will be said. Your earliest films tended to focus on bureaucratic incompetence. Films like these explore institutions but are far more hopeful.

Not everything is bad. Seeing good people doing good things and useful things and complex things well is just as good a subject as showing a horrible prison where people are abused. I don’t think it represents any evolution in my thinking so much as a wish to have the films display as wide a variety of human experiences as possible. There are even parts in “Law and Order,” your second movie, that show good things.

I agree. There are parts of “Law and Order” where the cops are doing a good job too.

Some of your films are very short and some a very long. “National Gallery” is the latter. What factors tend to inform length?

I have an obligation to make the best film I can out of the material, and that may not correspond to what someone in a television network thinks is an appropriate length for all films. My films range from 73 minutes, which is “High School,” to six hours, which is “Near Death.” A film comes out the way it comes out. I don’t set out to make a film that’s an hour and 18 minutes or three hours and six minutes. PBS has been extremely generous with me. I’ve never had a fight with PBS about length. I’ve had one or two fights about length, and they have been with foreign TV networks. You spent a long time shooting and editing on film, but with “La Danse” you started cutting digitally, on an Avid, and with “Crazy Horse” you started using digital cameras. How have you found that? I don’t particularly like editing digitally. I worked on a Steenbeck for 40 years. You can recover the material faster, but other than that, editing on an Avid system doesn’t give you any more choices. You have access to those choices faster. But the speed with which you have access to them isn’t necessarily a good thing. I’ve found myself with the Avid doodling. When you’re editing on film and all the rushes are hanging on the wall, you have to go to the wall, take the roll of film down, roll the film to the place you want. And while you’re rolling to the place you want you’re also reviewing material, you’re thinking about what you might do with it. It’s not wasted time. Fifty percent of editing is thinking and asking yourself questions. It has nothing to do with the editing system you’re using. It has to do with what’s going on in your head in relation to the rushes you’re watching. Shooting digital is cheaper and allows longer filming than on film. Do you shoot the same way?

I shoot exactly the same way. There’s a new Arri camera called the Amira which has the same fit to the shoulder than the old Eclair camera did. The Red camera is very good, but it’s not as easy to carry around. But they’re getting there. There are also preservation issues with digital.

Nobody, far as I know, has learned how to preserve the material longer than five years. If you want to preserve the final film, you have to make a 35mm copy. Depending on the length of the film, that can cost anywhere between 30 and 50,000 dollars. If you preserve something digitally, there’s no guarantee there will be a way to play it back.

The machine may not exist!

Or the file itself could be corrupted.

Maybe it sticks after six months. It’s a nightmare.

You have yet to transfer most of your back catalogue to Blu-ray. But have you been trying to get them online so that they’re easier to see? Netflix just in the last six months bought some of the DVDs for distribution. And I’ve been negotiating to get the films on VOD. I think in the next six months they’ll all be on VOD.

About raising money…

It’s a pain in the ass.

You’ve said the problem is people always assume you have money, when that’s not always true. How was raising money for “National Gallery”?

“National Gallery” was a bit easier, because I got money from a French subsidy program and from Canal Plus, in addition to money from PBS and ITVS. I can’t always count on getting money from the French. And the situation in America is terrible. The PBS budget hasn’t been raised in years. God knows what the new Congress is going to do with public television. The budget for the National Endowment for the Arts hasn’t been raised in years. Compare it to France, where one percent of the national budget goes to the arts. The total budget for NEA is something like $250 million. I’m sure that’s less than the city of Lyon gets in arts subsidies. There’s an essay about you from Errol Morris in which he calls you “the undisputed king of misanthropic cinema.” It’s very funny. But that’s an example of pure projection. Because if there’s any king of misanthropic cinema it’s him.

It’s never a problem. People don’t look at the camera. And the worst thing you can do is say, “Please forget about us, don’t look in the camera,” because that’s when someone will look in the camera. I try to demystify the process. Someone will say, “Is that a camera?” or “Is that a tape recorder?” I’ll say, “Yeah, would you like to see how it works?” So you put the camera on their shoulder and let them look through the eyepiece, or put the headphones on and hold the mic up and let them talk so they can hear their voices. That happens occasionally but not often. Everything’s out in the open. I try not to be unobtrusive and I try not to be threatening. And if someone wants to talk, I talk.

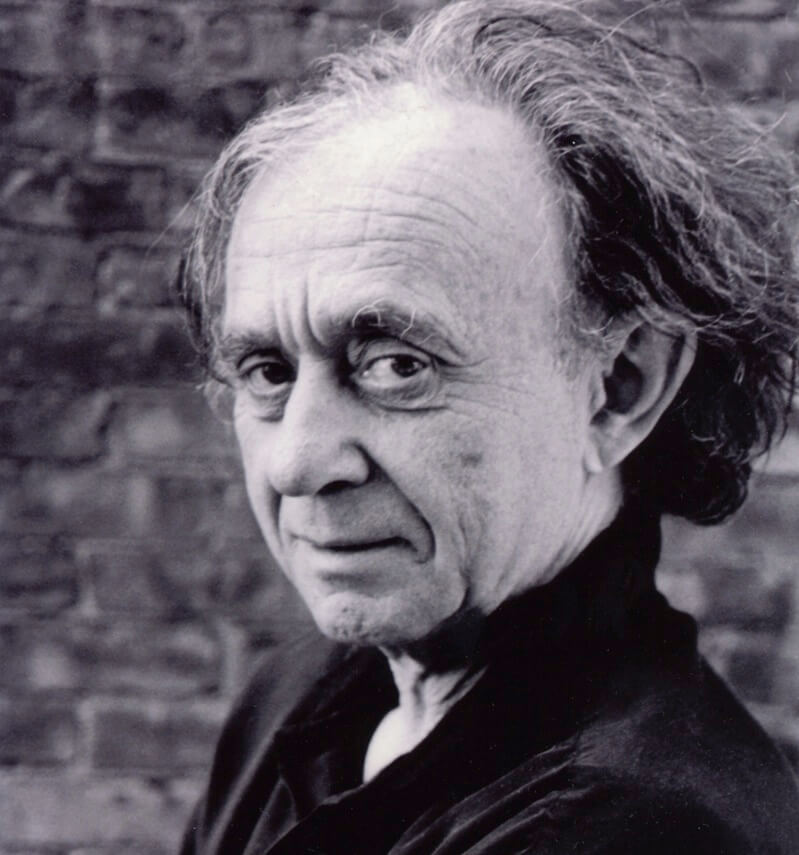

Interview: Frederick Wiseman talks ‘National Gallery’ and how ‘not everything is bad’

Zipporah Films

Follow Matt Prigge on Twitter@mattprigge