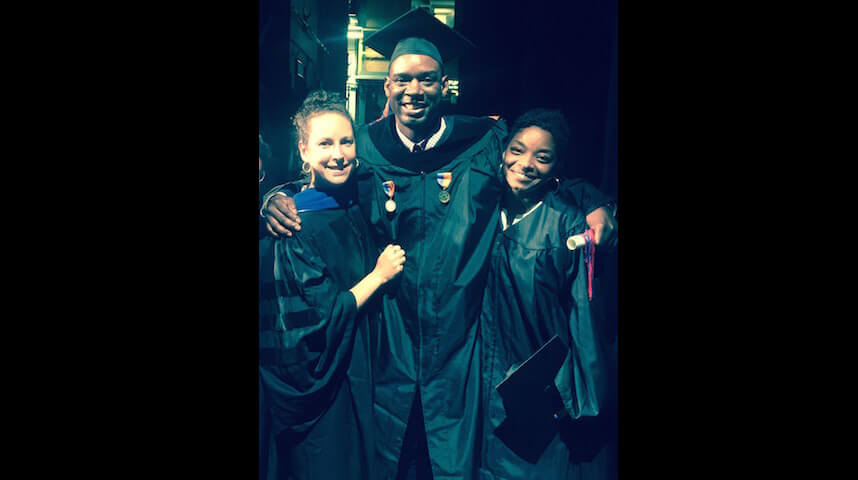

When Devon Simmons started college, he was not a recent high school graduate living on a bucolic campus. He was a prisoner at the Otisville Correctional Facility, a medium security men’s institution two hours from New York City. “To finally utilize my talents was really a blessing, and in the process I got to learn new things, and look at things from a different perspective,” says Simmons, 34, who began his coursework during the 12th year of a 15-year sentence. RELATED: Young artists put potentail on display Simmons was part of the first cohort of students in the Prison-to-College Pipeline program, an initiative of John Jay College of Criminal Justice and the Otisville Correctional Facility that began in 2011. The program is unique in that college credits earned behind bars are transferrable, allowing formerly incarcerated individuals to continue their education upon reentry. CUNY professors are brought in to teach at Otisville, and students in John Jay’s criminal justice programs travel to the facility once a month to learn alongside their incarcerated peers, challenging minds and stigmas in equal measure. “I had a sense of purpose, knowing that out of the hundreds that applied, I was one of the eight people who actually was accepted into the program,” says Simmons, who will begin studying at John Jay College in the fall. “Because no one in my family actually went to college, so it gave me an opportunity to rewrite my story.” RELATED: Scholastic Summer Reading Challenge aims to exercise young minds Soon, 12,000 prisoners across the country will have the opportunity to rewrite their stories too. In June, John Jay College was one of 67 institutions nationwide asked to participate in the Second Chance Pell Pilot program, which makes incarcerated students eligible for federal education funding. The program represents a major win for criminal justice reform — in 1994, the U.S. Congress banned Pell Grants to prisoners —and enables the John Jay program to nearly quadruple its enrollment, from about 30 to 150 students, says Dr. Baz Dreisinger, founding academic director of the Prison-to-College Pipeline and the author of “Incarceration Nations: A Journey to Justice in Prisons Around the World.” Says Dreisinger, “There’s increasing bipartisan recognition that education in the context of prisons is economically, morally and socially the right thing to do.”

Rewriting his story

In 1999, four weeks before graduating from high school, Simmons was charged with first degree assault and sentenced to 15.5 years in prison. In his first decade behind bars, he earned his G.E.D. and continued to seek knowledge, learning about the law in pursuit of appealing his case and reading numerous autobiographies, including Malcolm X’s, which gave him a sense of motivation and hope. Despite being out of the classroom for 12 years, Simmons knew he wanted to apply to the Prison-to-College program. To qualify, inmates must have high school diplomas or G.E.D.s, be eligible for release within five years and go through a competitive application process that includes writing a letter of interest and passing the City University of New York (CUNY) assessment tests. The program’s coursework is rigorous, and students are encouraged to think critically about the world beyond prison walls. Simmons’ assigned readings inspired him to study texts outside the class, such as Desmond Tutu’s “No Future Without Forgivenes.” For one assignment, Simmons wrote about the importance of funding education for incarcerated individuals. “The truth of the matter is, higher education has proven to be cost-effective in regards to recidivism,” says Simmons. “I don’t see how society wouldn’t embrace that when ultimately, these are individuals coming back to their community, right?” Another aspect of the program he’s most proud of is the ripple effect on those around him.

“I would like people to know how infectious it [education in prison] is. It spreads like a disease. Because I might be the one sitting in the dorm who’s actually taking college courses in the facility. When other people in the dorms see me up late at night doing my papers, constantly reading books, they begin to wonder, and with that, they start asking questions and saying, ‘Wow, if this guy could do it, maybe I could get my GED, maybe I could engage more in my vocation or trade,’ or whatever it is they’re doing to better themselves.” Now on the outside, Simmons is a student success mentor at John Jay, where he speaks in classrooms about the criminal justice system.

Says Simmons, “I have a lot of power when I come into these classrooms, especially these criminal justice classrooms, because I bring a different perspective. These textbooks, they talk about incarceration, and they talk about policing, but they don’t really talk about the perspective from a prison’s view, or they don’t talk about the individual who has been arrested.” It’s also in the classroom where Simmons has space — to voice his opinions, and challenge misconceptions about incarcerated individuals. And it’s not just sitting in a classroom, but being anchored to an institution, that allows him to do so. “Now if I wasn’t in college, and I was just somebody [who got out of prison], people would say, why are you questioning police brutality? Why don’t you just follow the rules? But as a student, it gives me the liberty to question everything. It gives me the liberty to question who, what, where, why. That’s critical thinking. So, that’s why I take great pride in being a student, because it alleviates the stigma as a convict who has a disregard for the system for the rules of society.”

Back on their feet, and finding their voice

istock