Aboriginal gangs are proliferating across Canada as criminal organizations exploit the intense poverty and squalid conditions that many First Nations youth live in, says a top officer with the RCMP’s aboriginal police division.

The gangs’ stock-in-trade includes drug distribution, prostitution and theft, and they’re only growing more sophisticated, said the RCMP.

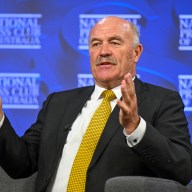

“The gangs are brought on by poverty,” said RCMP Sgt. Merle Carpenter, who holds the aboriginal gangs file with the National Aboriginal Policing Services.

“They intimidate by violence and these aboriginal youth are just wanting to belong to somebody.”

While Winnipeg, with its large aboriginal population, is still the epicentre for native gangs, outfits like the Indian Posse, the Manitoba Warriors and the Native Syndicate have spread from coast to coast and into the far North.

“They are certainly increasing in numbers and becoming more sophisticated in how they do business,” said Carpenter, who is a member of the Inuvialuit First Nation in the western arctic.

The gangs are growing through the country’s network of jails, which are acting as hothouses for recruitment and learning the tricks of the trade.

If you’re not a member of a gang when you go to jail, police officials in Manitoba say, you will be when you come out. Many prisoners simply cannot survive jail life without the protection of a gang.

Last week, an aboriginal policy conference in Ottawa heard that aboriginal youth membership in gangs could double in the next 10 years.

Dr. Mark Totten, a sociologist and expert on Canadian street gangs, released a study that found aboriginal gang violence has reached “epidemic levels” in many communities.

Totten said female aboriginals are often traded among gang members and, as part of their initiation, are made to have sex with numerous gang members at the same time.

Observers say the explosive growth can’t be combated unless the federal government steps up and addresses the woeful conditions underlying the startling trend.

“It’s so simple that it’s hard to understand why nothing’s happening,” said Steve Koptie, an aboriginal social worker who spent several years working in the mental health field for 21 reserves in Ontario’s northwest.

“It’s all about education and employment. If we don’t get youth educated and we don’t get them… participating in the workforce we’re going to continue to watch this deterioration.”

Koptie notes there is vast mineral wealth in Canada’s North, such as the Ring of Fire in northern Ontario, which can provide jobs for many now-destitute aboriginals.

“The issue is how are we going to share the resources and how are we going to make education a priority,” said Koptie, who notes schools on reserves get half the funding of schools off reserve.

“The federal government is responsible for education on reserve and they’re fallen so far behind, they’ve dropped the ball majorly on this.”

Calls to the federal Ministry of Indian and Northern Affairs for comment were not immediately returned.

Vancouver and the lower B.C. mainland, with its close proximity to the United States and its oceanic coastline, have become a major gateway for the importation of drugs in the last few years, said the RCMP.

But alarmingly, the native gangs are spreading into rural B.C. as well recently, including Vancouver Island, the B.C. interior, Fort St. John’s in the northwest and Prince Rupert on the northwest coast.

Smaller gangs are springing up there, with names like Red Alert, Cree Boys, Native Blood and Native Posse.

They are now in all corners of the province, said Supt. Dan Malo, the RCMP’s officer in charge of the Combined Forces Gang Task Force in B.C.

“In all the locations and corners of this province, there are people who use drugs,” said Malo.

“Where there’s a consumer base there’ll always be a seller, and that’s where some of our native gangs seize the opportunity.”

Aboriginal gangs are easily migrating eastward from Winnipeg into northwestern Ontario as well, often using relatives and friends as drug and alcohol couriers into even the most remote fly-in reserves, via plane or winter ice-roads.

“In one of the northern communities I was in, I met a young man with rope burns on his neck, he was 17 years old, and a gang member from Winnipeg had been in the community and he gave him one week to come up with $1,500,” said Koptie.

The young man decided he was going to kill himself because he couldn’t come up with the money, he said.

“This is happening across the country.”

The criminal gangs are even spreading as far north as Iqaluit, Whitehorse, Yellowknife, Inuvik and the Arctic, said Carpenter.

Oil and gas exploration meant there was a “lot of money in that neck of the woods.”

“If there’s money to be made, they’re going to be there.”

One-time geographic boundaries, in which gangs used to control a certain turf-specific areas of towns or cities, are blurring.

Now, in any given neighbourhood in Winnipeg, for instance, all the gangs will be represented, said Mitch Bourbonniere, a Metis and veteran social worker who has spent decades pulling aboriginal kids out of gangs in Winnipeg.

“The higher-up guys who are smarter know not to make trouble for each other,” he said.

“They’ve all learned to kind of co-exist because they all know they’re all in it for the same reason, and that is to make money.”

The gangs are evolving in other ways as well, learning police and Crown attorney tactics across the country, Carpenter said.

“It’s just cat and mouse. If you are doing a big operation on one gang and put them all in jail, well another gang pops up,” he said.

“It’s a supply and demand issue and its just a never-ending cycle.”

Carpenter said he thinks much can be done at the community level about the gang proliferation.

“The police can’t do it alone.”