VANCOUVER, B.C. – Olympic organizers conceived of a relay that would tell the story of Canada via 12,000 pairs of red-mittened hands clasping the Olympic flame.

They didn’t expect those mittens to end up everywhere from on the paws of Husky the Musky in Kenora, Ont., to the dinosaurs in Drumheller, Alta.

“It’s gone from strictly passing the flame from hand-to-hand and community-to-community to really building a nation,” said Jim Richards, director of torch relays for the Olympic organizing committee.

The torch, perhaps the most poignant symbol of the Olympics, returns to B.C. on Thursday for the final three weeks of its journey, ending with the start of the Games on Feb. 12.

“That geographical message is going to say: ‘We are in B.C., we are on our way home now, it’s real,”‘ said Richards.

Since the flame was but a spark in the cauldron in Ancient Olympia, Greece, some elements of the relay have been highly anticipated.

Day One provided an inkling of what was to come for both sides.

Thousands of people packed the grounds of the B.C. legislature to watch the arrival of the flame, a scene that would repeat itself over and over again in the days to come.

But behind-the-scenes, there was the typical harried chaos that kept organizers on their toes, like the announcer at the arrival ceremony in Victoria not being able to see what was happening on stage and cutting off high-profile leaders’ remarks.

Later that evening, an anti-Olympic protest turned unruly, forcing torch run organizers and police to divert the relay, dampening the excitement of a handful of torchbearers who, rather than running their 300-metre stretch, instead stood on the side of a road and handed the flame off to one another.

It was the first in a series of protests that would dog the relay, creating moments alongside the road that were as meaningful as those for the thousands of torchbearers themselves.

In Kahnawake, Que., a last-minute negotiation saw the relay cancelled in favour of a simpler flame event so as to avoid inflaming Mohawk-RCMP tensions.

It was a move that was seen as both a victory for Mohawks but also for aboriginal involvement in the Games.

“We’ve been saying we’re full partners in the Games. Well, you don’t really become full partners until you have to deal with some adversity,” said Tewanee Joseph, executive director of the Four Host First Nations society, the group representing the four bands whose traditional lands are home to the Games.

It was also an example of the various Plan Bs organizers have had in place, including what to do in harsh weather.

For all the planning, there were also the surprises, like three marriage proposals along the way.

There were the high moments – like the flame’s arrival in Alert, the northernmost inhabited point in the world, where 20 members of Canadian Forces Station Alert who dubbed themselves “The Frozen Chosen” ran with the torch.

There were also the frustrating ones – in Churchill, Man., the famed polar bears couldn’t be found when it was time for a photograph with the flame, disappointing relay sponsor Coca-Cola who has the bear as one of its iconic mascots.

The flame also went out a couple of times while up north, forcing Bombardier to make an on-the-fly adjustment to keep it going in extremely high winds.

And so many more torch bearers spent the $349 plus tax to buy their torch than organizers anticipated that they didn’t make enough display stands to go with them.

Torch bearers have snowmobiled, jogged, surfed and skied with the flame and even those used to the limelight gasped out descriptions of wonder after their 300 metres of holding the torch aloft.

“You look at the people out there, you see the signs of the excitement,” said hockey star Sidney Crosby about the massive crush of fans who slowed his jog in Halifax in November to a crawl.

“You never dream of carrying the torch. For me, that wasn’t something that I ever thought would be a possibility.”

When anti-Games activists look out over the relay, they also saw excitement – what had been a largely local protest movement had finally gone national.

In several places, protesters under the banner of “No Olympics on Stolen Native Land” managed to divert the relay, in other locations they merely chanted along the way.

“The really good side of having this cross-Canada wasteful extravaganza is that it has brought people together all across the country because they can all see the effects,” said Mik Turje, who was one of the people involved in planning the first protest in Victoria.

“I think our hope is that we are going to see all the energy that has been going into resisting the Olympics to start moving towards a more united anti-poverty movement, a more united indigenous movement and a more united environmental movement.”

The budget for the Olympic relay was around $21 million, with Coca-Cola and RBC paying half.

The federal government also contributed $14 million to the relay, up $2 million from their initial pledge in order to help organizers cover off the costs of the community celebrations held twice a day.

The relay was also pricey for police.

The RCMP-led integrated security unit in charge of the relay spent a reported $4 million on the route, including background checks for every single torch bearer and $150,000 alone on training their officers for the run.

The price tag didn’t include thousands more spent by local police units and communities on their celebrations.

Victoria police went as far to submit a tab to Olympic organizers, though they admitted they didn’t expect to see it paid.

International media were also paying attention.

With some of the $26 million they’ve received to help increase tourism to Canada as a result of the Games, the Canadian Tourism Commission brought 14 athletes and broadcasters from key markets like India and China to run with the torch.

In addition to their run, the celebrities participated in local activities like dog-sledding, wine tours or just community events like local hockey games.

Suddenly, footage of Saskatchewan was playing in Paris.

“For us, bingo – it’s a home run when they pick up all that other footage,” said Gloria Loree, executive director of communications for the commission.

But now all eyes will train on B.C. as the torch crosses the provincial boundary and where the protests are expected to escalate in tandem with the crowds on the roads.

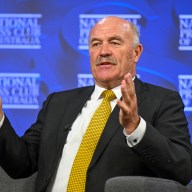

It’s a moment that B.C. Premier Gordon Campbell can’t wait for.

“I think the torch has got a special place in all Canadian’s hearts,” he said.

“But I think in British Columbia it is going to fire up the province for the next 25 years.”