When Chris Biblis was diagnosed with leukemia at age 16, doctors knew he’d survive only with radiation treatment. Unfortunately, Biblis’ testicles had to be radiated, too. Chris would be infertile.

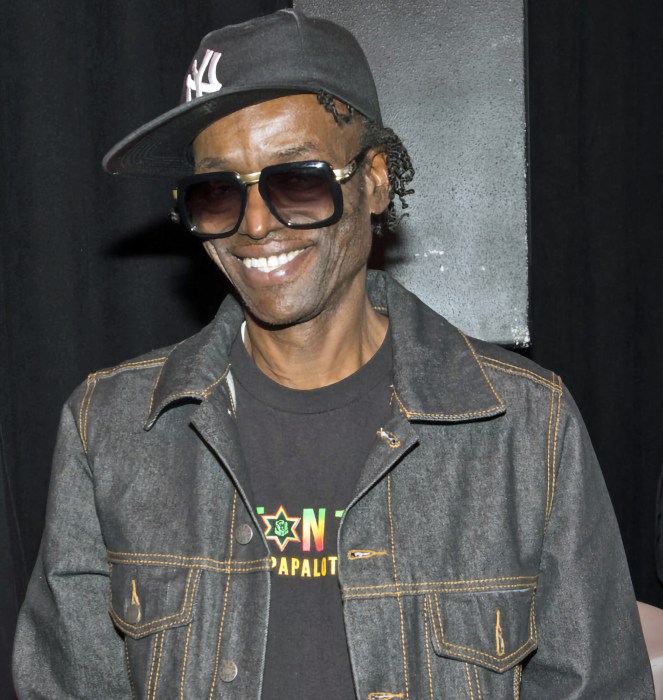

It was 1987. Back home in Alabama, Biblis’ mother happened to read a news article about British doctors who froze sperm. She decided she wanted her son to freeze his sperm, too, to give him a chance of later having a family. “I sort of thought it was a good idea,” recalls Biblis, now 40, “but it was totally embarrassing. I had to drive several hours with my father to give the specimen.”

Biblis’ unusual choice paid off: Last year, he and his wife welcomed a healthy baby, Stella. She was conceived using Biblis’ 22-year-old sperm. “It was like any other in-vitro [test-tube] pregnancy,” explains Chris’s wife, Melodie. “When we decided to do it, we didn’t realize that it was somehow unusual to use 22-year-old sperm.”

It was: Only one baby has ever been conceived using older sperm. That’s because in 1987, sperm-freezing of any kind was highly unusual. But today, young male cancer patients are routinely asked to give sperm specimens, to be stored until they’re ready to start a family.

Today, female cancer survivors, too, have better chances of conceiving. Eggs can now be frozen using rapid-freezing technology that makes them more viable; about one-fifth of frozen eggs result in pregnancies.

“But women can’t just provide eggs for freezing,” explains Wing. “It takes two to three weeks to prepare their ovaries for ovulation, and the eggs’ viability and quality depend on the woman’s age and health at the time of egg-freezing.”

In the past, young single women with cancer faced the dilemma of freezing their eggs with little chance of success or fertilizing their eggs using a sperm donor.

But even with optimistic prospects of post-cancer parenthood, many turn down their only chance. “My estimate is less than a quarter of those young cancer patients of either sex, those who really need it, undergo fertility preservation,” says Dr. Kutluk Oktay, director of the Institute for Fertility Preservation at New York Medical College.

When Chris Biblis delivered his sperm sample, he had no thought of his little Stella, now teething. “I feel more lucky to be alive after cancer,” he says. “But I feel more lucky being a father.”