Building a barrier across Boston Harbor to protect the city from flooding would be “not prudent,” according to a new study which instead recommends focusing attention on land-based coastal protection efforts like berms, walls and zoning policy.

The report, which the Sustainable Solutions Lab at University of Massachusetts Boston released Wednesday, advises against pursuing a harbor barrier, finding that such a project would have low cost-effectiveness and a limited useful life.

“Our overall conclusion is that right now it doesn’t make sense for the city to consider any kind of harbor-wide barrier system,” said lead author Paul Kirshen, the academic director of the Sustainable Solutions Lab. “It doesn’t make sense for decades, if not ever, to consider a harbor-wide barrier system when you compare it to the advantages of shore-based system.”

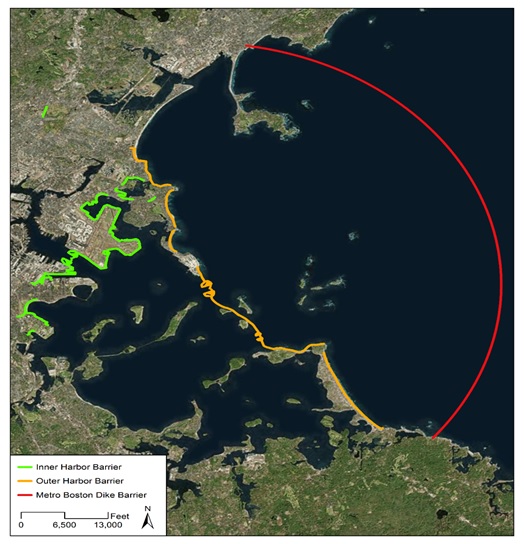

The report examined the feasibility of both an inner harbor barrier, from Logan Airport to the Seaport, and an outer harbor barrier from Winthrop to Hull. Depending on the version pursued, the cost could range from $6.5 billion to $11.8 billion, the report said.

The report was sponsored by the Boston Green Ribbon Commission, which bills itself as a collection of business, institutional and civic leaders working to develop strategies to fight climate change.

The overall cost for shore-based coastal protection would come in around $1 billion to $2 billion, and that money would likely come from a variety of sources, including the private sector, said Bud Ris, who co-chairs the commission’s Climate Preparedness Working Group.

“I think the flooding from this last winter was a great wakeup call, and we’ve seen a lot of interest from people in the business community for tackling this problem,” Ris said. “I think they understand maintaining the market value of their properties is crucial to being sure that they’re well protected. There’s no question it’s a big challenge to come up with that kind of money of a billion to 2 billion, but that’s certainly a lot easier than coming up with eight to 15.”

Ris said the commission decided to look more closely at the feasibility of a harbor barrier because “everybody asks about it all the time.”

“Everybody wanted to know whether this is something that we should jump on quickly, but I think they’re also familiar with what happens with really large complex projects, particularly like the Big Dig in the past, which probably everyone at this point is happy we did,” Ris said. “But remember, that started out at 6 or 12 billion and ended up at 20 to 25 depending on which number you use. I think people know that these big, huge projects can become really complicated and troublesome, so I think they will be sort of relieved to know that this is not an option to pursue for now. Let’s get on with the things that we really know can work along the neighborhoods that are vulnerable.”

The harbor barriers considered in the analysis would use gates that remain open except during flood conditions, and Kirshen said the gates would need to close more often as sea levels rise and flooding becomes more frequent, eventually leading them to wear out mechanically.

The report also cautions of “navigational and safety issues” for recreational and commercial boats because of “anticipated increased water velocity in the barrier openings,” as well as “greater vessel congestion” near openings in the outer harbor barrier. An outer harbor barrier “could also impact the abundance, distribution and behavior of fish populations,” the report said.

On-shore resilience plans in coastal neighborhoods provide a “great deal of flexibility” and can be adapted as climate change projections and sea level rise estimates develop over time, Kirshen said. He said they can also bring benefits to residents like more open space and parkland, which a harbor barrier would not provide.

Kirshen pointed to Boston’s “Climate Ready Boston” initiative as an example of shore-based resilience efforts. Ideas in that initiative include elevating part of Main Street in Charlestown, redeveloping the nearby Schrafft Center waterfront with “elevated parks, nature-based features and mixed-use buildings,” and elevating part of the Harborwalk in East Boston, in combination with a “deployable flood wall across Lewis Street.”

The earliest a harbor barrier could be up and functioning would likely be 2050, according to the report.

Kirshen said design, permitting and construction of a barrier system would take about 30 years, and could be a possible option decades from now. In the meantime, he said, the effectiveness of onshore projects should be monitored so those efforts can be adjusted if needed.

“We’re confident that the shore-based solutions, if implemented correctly, can get us through 2070, 2080, under the high scenarios of sea level rise we’re facing now,” he said. “So the earliest we might need a barrier system would be near the end of the century, and we can start doing more detailed studies around 2050 if we had to.”