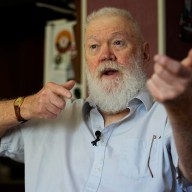

Philip Rhys, left, mentors Javier Gutierrez at George Washington Preparatory High School.

Philip Rhys, left, mentors Javier Gutierrez at George Washington Preparatory High School.

Credit: Aaron Lucy

Javier Gutierrez lives in his uncle’s garage; his mother kicked him out when he didn’t want to enlist in the Army. He nearly dropped out of school, too, so bad were his grades. But Gutierrez, a strikingly handsome 18-year-old in Los Angeles, has turned his life around – as a Shakespearean actor.

I meet Gutierrez after a rehearsal with the Inner City Shakespeare project at the George Washington Preparatory High School in South Central Los Angeles. This is one of Los Angeles’ most notorious neighborhoods: poor, violent, gang-infested. Few middle-class people ever set foot here. But as I enter the gymnasium, Gutierrez and some 20 other Latino and African-American teenagers are busy perfecting their lines from Shakespeare’s “Twelfth Night” in one-on-one sessions with British actors.

“My drama teacher dragged me here two years ago,” Gutierrez tells me. “She said she’d flunk me if I didn’t audition. I didn’t want to go at all. I hate reading; I hate books. But I did read a bit of ‘Romeo and Juliet.’” Even though Gutierrez could barely understand the words he was reading, he soon felt he could relate a little to the characters. When he auditioned, he got the role as Romeo. The next year he played Puck, the lead role in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.”

Gutierrez and his fellow actors are performing the 16th century plays against huge odds. “South Central LA is a world unto itself,” explains Kathy Haber, the energetic founder of Inner City Shakespeare. “Often the kids are attacked as they walk home from our rehearsals, and they’re often asked which gang they belong to.” Adds Phillip Rhys, a British Hollywood actor who mentors Gutierrez here. “These kids all know people who’ve been shot and killed. Javier’s mother has disowned him. But just by being here, they realize that centuries ago there was this guy who was just an actor, too – nothing fancy. We spent a whole day cursing like Shakespeare.”

But their afternoon identity as actors can offer them a way out of a near-certain life of crime. “Just because you’ve got colored skin it doesn’t mean you shouldn’t be exposed to the classics,” says Melanie Andrews, the teacher who forced Gutierrez to start acting. “If we don’t get them hooked on this, they’ll get hooked on drugs.”

Jamielee Rodriguez, a vivacious 17-year-old, played Juliet in “Romeo and Juliet,” Hermia, the female lead in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream,” and now she’s back again. “When I started, I didn’t understand what I was reading, but when the mentors explained it, it made sense,” she tells me after her rehearsal. “Now it helps me with school.”

At the rehearsal I also meet Neil Dickson, another veteran British actor who serves as a mentor. “This program changes lives!” he exclaims. “These kids are on the verge of crime. On their first day here they look at Shakespeare and have no idea what it all means. Three months later, they’re in a production, proudly wearing their Elizabethan costumes, even though the other kids make fun of them. It’s so inspiring!” Indeed, almost every teenager in the “Romeo and Juliet” production has gone on to college.

Gutierrez still doesn’t much like books, but now he does read Shakespeare. “He was a crazy dude who wanted to kill his uncle,” he summarizes. “I’m a dark kid. I can relate to that.”

‘Shakespeare for poor teenagers’

Theater and teenagers form a fruitful and combustible combination. “Dead Poets Society,” the 1989 surprise hit movie, portrayed the lives of a group of private school boys who wanted to perform Shakespeare (inspired by their teacher, portrayed by Robin Williams). Neil, the boy at the center of the film, was chosen for the role as Puck in “A Midsummer Night’s Dream.” But, just like Gutierrez, he faced huge obstacles: in this case, his father’s opposition. After the performance, he killed himself.

This are bound to end better for Gutierrez, who – assisted by his theater mentors as friends – has improved his grades to the point where he can now go on vocational college. “I want to encourage teachers everywhere to use Shakespeare to do something for poor kids,” Andrews says. “It helps them to be better people.”

And, adds Katy Haber, this is a model that could work anywhere in the world. “It doesn’t have to be Shakespeare,” she reflects. “In France it could be Dumas. This is about giving disenfranchised youth a chance to tap into another world.”