By Ed Cropley

LUANDA (Reuters) – A month ago, a 17 ton shipment of bananas left Angola for Portugal in what state media heralded as a “first symbolic batch” in the resurgence of a farming sector wiped out by civil war. But that war ended 14 years ago and since then Angola has overlooked agriculture, developing instead an addiction to oil income and the imports it buys. Now, with crude less than half its price of two years ago, the country appears to be grinding to a halt. Africa’s top oil producer needs more than a container load of fruit to solve a financial and economic crisis – compounded by a public health crisis – that has laid bare the failings of the “diversification” mantra of Jose Eduardo dos Santos, its president for the last 37 years. Oil wealth turned Angola into sub-Saharan Africa’s third-biggest economy and one of the continent’s few “upper-middle income” states. But beyond the high-rises on the capital’s Dubai-style coastal promenade, the problems are plain to see. Cranes stand idle atop half-finished concrete office blocks in Luanda while piles of rubbish lie uncollected in the streets, a result of municipal budget cuts imposed this year to try to balance the books. The squalor is a breeding ground for vermin, flies and disease, and health experts say it is no coincidence that a yellow fever epidemic that started in December in one of Luanda’s vast slums has spread across the country and beyond, reaching even China. “Luanda is dirty, disgusting,” said 58-year-old businessman Antonio Bobbe, edging past a vagrant rummaging through a mound of trash. “The government doesn’t do anything. There’s no responsibility. You should see the rats. They’re huge.” On top of the filth, a shortage of hard currency makes doing business tough for anyone but the well-connected. “If you have friends, government friends, you can get dollars. If not, nothing,” said Bobbe. “We hope that the situation changes, but at the moment there’s no light at the end of the tunnel.” “ANGOLA RISING” NO MORE

Before independence from Portugal in 1974, Angola was a major exporter of fruit, coffee and sisal. Then two decades of conflict destroyed commercial agriculture and since peace returned in 2002 problems ranging from uncleared mines in sugar plantations to uprooted rural workers have frustrated efforts to revive it. While Angola has rebuilt an impressive infrastructure, getting any sort of productive industry off the ground has gone nowhere apart from the oil on which it relied to achieve breakneck economic growth. It now churns out 1.8 million barrels a day from its offshore fields and is China’s leading crude supplier. But those petro-dollars come at a price.

Oil accounts for 40 percent of GDP, 70 percent of government revenues and 95 percent of foreign exchange income, leaving the nation of 25 million people dangerously exposed to fluctuations in world oil markets. With crude languishing at $50 a barrel, down from over $100 in mid-2014, Angola is starved of dollars. Growth has slowed to 3 percent – almost a recession in local terms – while the national currency has collapsed and inflation in a country that imports almost everything hit an annual 29 percent in May. For dos Santos, a Soviet-trained oil engineer regarded as the pillar of post-war stability, the timing of the twin crises could not be worse. They have struck a year before an election and two years before what the 73-year-old president has said will be his retirement. “The fragilities of the post-conflict state that dos Santos has built are being exposed,” said Paula Roque, an Angola expert at Britain’s Oxford University. “That whole rhetoric of ‘Angola Rising’ no longer holds.” Desperate, the government swallowed its pride and sought help from the World Health Organization against yellow fever but last week the International Monetary Fund said Luanda had ended talks about a broad financial rescue package. The government has not commented and finance minister Armando Manuel did not respond to requests for an interview.

GOLDEN GOOSE

Besides yellow fever, few indicators are as telling as the kwanza currency, down more than 40 percent in the last year against the dollar at the official central bank rate.

Available only to a lucky few individuals and firms, the rate is of little consequence to ordinary Angolans, who have to rely on a black market where the kwanza is worth as little as 570 to the dollar, less than a third its official value of 165. “For people bringing in anything from the United States or South Africa it’s very difficult,” said 26-year-old Nadio Medina, who used to import used cars from South Africa. Now he sells eggs wholesale to pavement burger stalls. In an unusually frank admission last month, dos Santos admitted that bloated state oil company Sonangol, the central pillar of the economy and the source of nearly all its dollars, had not paid a cent into state coffers since January. “Our country lives upon imports – imports for food, for raw materials to national manufacturers, for industry, agriculture, construction,” he said. “We need to make other goods to export besides the oil. That is a strategic task.” Yet looking past the rhetoric, the only thing likely to change is Sonangol.

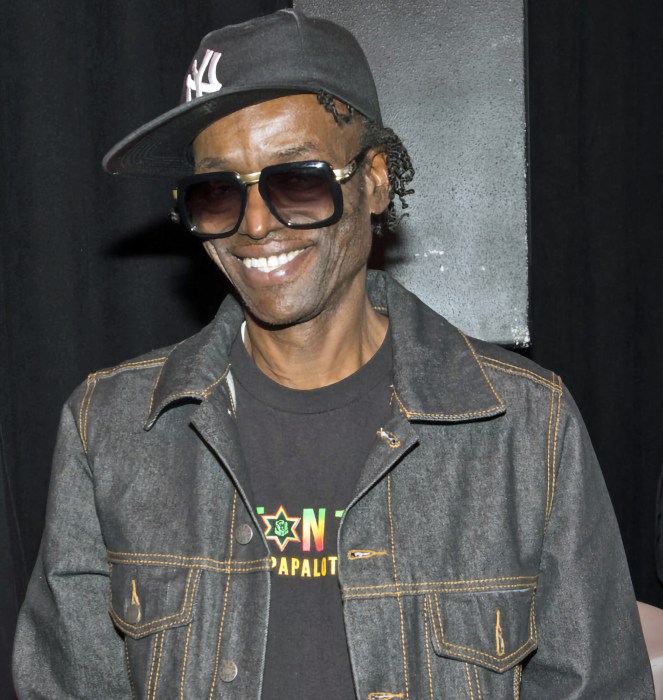

Last month, dos Santos made his 43-year-old daughter Isabel chief executive, inviting cries of “supersonic nepotism” from anti-graft website Maka Angola, a rare dissenting voice in one of Africa’s most politically-closed states. Last year, for instance, 17 members of a Luanda book club were jailed for reading a volume described as a “blue-print for non-violent resistance to repressive regimes”.

Isabel dos Santos – said by Forbes magazine to be Africa’s richest woman – insisted her appointment was everything to do with shaking up Sonangol and nothing to do with a dynastic dos Santos succession plan, as her father’s opponents allege. “It’s not because of politics. I was brought into this project because of my experience from the private business sector,” she told Reuters in an interview that laid out her central aim: to produce more oil for less money. Foreign oil firms Chevron and BP applauded her plans that include having Boston Consulting Group and PriceWaterhouseCoopers as advisers and stripping out Sonangol’s real estate, banking and aviation units to focus on oil. To many, the overhaul is the clearest sign yet that President dos Santos really is preparing for retirement but not necessarily to make way for his daughter.

“It’s not about Isabel becoming president,” said Alex Vines, head of the Africa program at London’s Chatham House think-tank. “The regime relies on Sonangol. It’s the goose that lays the golden egg and the reason she was put in charge is because it needs serious reform.” (editing by David Stamp)