By Edward McAllister and Sebastien Malo

NEW YORK (Reuters) – Before this week, Harriet Richardson’s retirement dream was still intact: work a few more years in the United States before heading back to find a quiet, ocean-front house in her native Puerto Rico. Now she’s not so sure. Over a plate of fried plantains and rice at El Nuevo Bohio restaurant, a lunch spot popular with Puerto Ricans in New York’s Bronx borough, Richardson, a corrections officer, said Puerto Rico’s debt crisis may derail her plan. “I wanted to be a beach bum, have a house by the ocean,” said Richardson, 46, one of the thousands of Puerto Ricans who migrated to the mainland United States in recent decades.

“If it doesn’t get any better, then I will think about somewhere else.”

Richardson isn’t alone. In interviews across New York this week, Puerto Ricans expressed weary frustration at the U.S. territory’s $73 billion debt burden and fiscal crisis.

Many Puerto Ricans said they expected more would leave for the United States because of the crisis, including family members, potentially accelerating a growing number of migrations in recent decades. Others have begun sending more money home to family and friends. Puerto Rico’s troubles came to a head this week as it faced a deadline to repay its debt and as a report from former International Monetary Fund economists said the commonwealth was in dire need of economic reform. Puerto Rico, whose economy has been in or near recession for nearly a decade, is staring at possible austerity measures that could result in higher taxes, suspension of the minimum wage and fewer public-sector jobs, such as those for teachers. At another table at the bustling El Nuevo Bohio in the Bronx, Livea Hernandez, a 59-year-old assistant teacher, said her mother was planning to sell her condo in Isla Verde, a small island near the capital San Juan. “It’s so bad she is going to sell her property and she is not going back,” Hernandez said. “Maybe for tourists it’s good, but for us, I prefer to spend my money in other places.” For Puerto Rican New Yorkers, many of whom still have family back home, 1,600 miles (2,500 km) away, the crisis is just the latest episode in a long decline that has hit the Caribbean island in recent years and caused an exodus to the United States. As of 2013, the 5.1 million Puerto Ricans living stateside outnumbered the 3.4 million living in Puerto Rico, according to Census data. The number of mainland-born Puerto Ricans outnumbers the island-born population living on the mainland United States, according to the Pew Research Center. Puerto Ricans now make up nearly 10 percent of the total U.S. Hispanic population, over 1 million of whom live in New York. Victor Cuevas, 67, who works at the El Barrio Music Center in Harlem and who moved to the United States 14 years ago, said his daughter is planning to join him this month, a move prompted by the crisis. BIG AMERICAN SHOWCASE

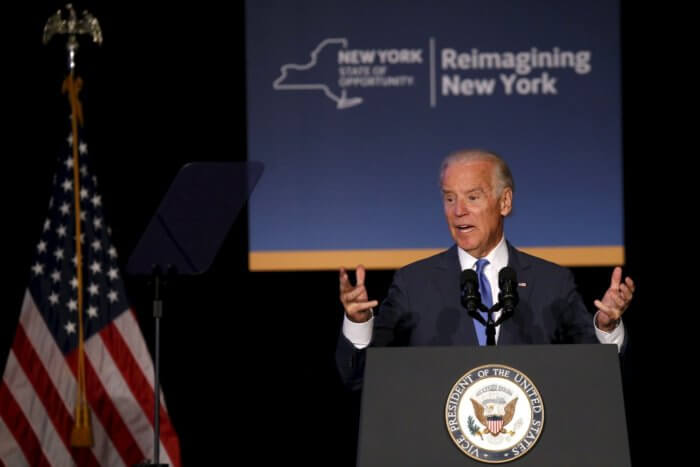

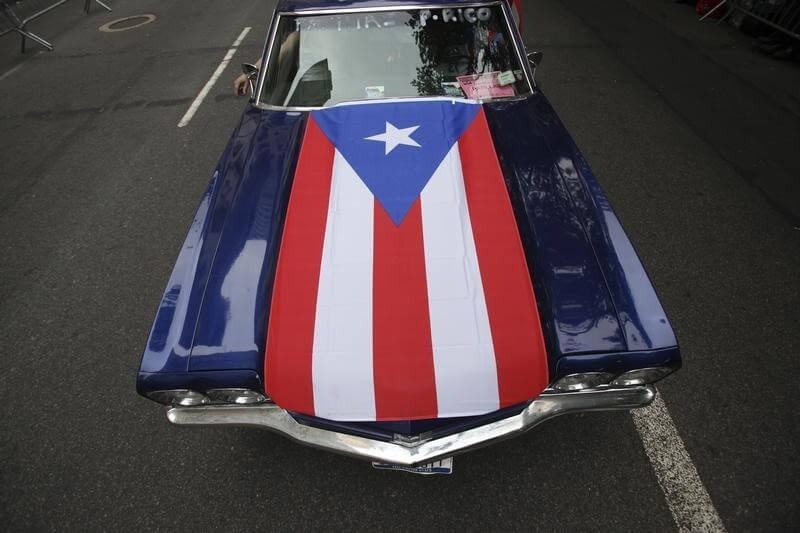

Puerto Rico has an unusual relationship with the United States. Puerto Ricans are U.S. citizens but because the island is a commonwealth and not a state they cannot vote in U.S. presidential elections. “Puerto Rico at one point was a big American showcase of how the United States took over this island and turned it into this great democracy,” said Angelo Falcon, president of the National Institute for Latino Policy. “Right now that colonial experiment is not going so well, it looks like it’s failing.” New York City remains a proud cultural magnet, particularly parts of Harlem in northern Manhattan and the south Bronx that became home during a huge migration wave after World War Two. Record stores sell Puerto Rican music, the nation’s flag hangs in store windows. Spanish is the language of the street. Puerto Ricans pride themselves on their ability to adapt and survive, despite their homeland’s woes.

Manuel Thillet, a retired mechanic, arrived in New York in the 1960s to make money for his family back home. He visits his home town of Santa Isabel every few years but says he will never return to live. “I have my Medicaid, help from social services. Over there, there is nothing,” said Thillet, 61, sitting on a low stool outside the Taino Mayor Records store in the Bronx, Puerto Rican flags flapping above his head. Thillet has doubled the amount of money he sends home to family – sometimes as much as $300 a month – due to the growing economic crisis.

Chatting with three friends on a street corner in the Bronx, Santiago Wilfredo, 61, said he moved to the United States 30 years ago, and had considered going back to Puerto Rico. But then the debt crisis hit. “I thought about going back but now it will be difficult,” said Wilfredo, who is unemployed. “With all that’s happening now, what am I going to do there, die of hunger?” (Reporting by Edward McAllister and Sebastien Malo; Editing by Leslie Adler)

For New York Puerto Ricans, debt crisis begins to hit home

By Edward McAllister and Sebastien Malo