It would not be a stretch to say that public art saved New York City. The first murals and statues free of museum curation and art galleries came along in 1967, at a time when the city was buckling beneath crime and budget deficits.

“Mayor John Lindsay was keen on the idea of supporting the arts, supporting creative programming as a way of maintaining New York’s sense of excitement and livability and attractiveness at a time when cities are teetering on the brink,” explains Lilly Tuttle, the curator of Art in the Open, a sprawling retrospective of 50 years of public art now open at the Museum of the City of New York.

Now it’s difficult to imagine the city’s streets, parks, buildings and subways without the energy — and, yes, occasionally controversy — that public art brings. Art in the Open covers the good and the bad with over 125 objects, including original public artworks like Rob Pruitt’s The Andy Monument and one of Kara Walker’s Sugar Baby attendants, covered in molasses per her directives.

Central to the exhibit are a few works that changed the city forever. Here are the six most influential — for better or worse — public art projects in New York City history.

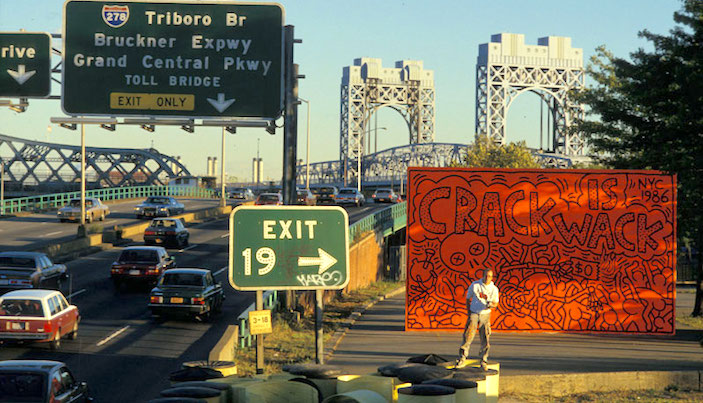

Keith Haring with his original Crack Is Wack mural, 1986. Credit: The Keith Haring Foundation

Crack Is Wack: What is graffiti vs. art?

If there’s one artist who truly democratized public art, it’s Keith Haring, who painted murals all over the city, indoors and out, and was among the first non-graffiti artists to use the subway as his canvas. In 1986, he created his most memorable piece: the neon orange Crack Is Wack mural at a Harlem handball court.

“This was at the height of the city’s crack epidemic,” recalls Tuttle, noting that Haring had an assistant who had become addicted to crack. “It’s right on Harlem River Drive; he really meant it as something akin to a billboard where people would see this and take his message.”

Haring was arrested and the mural painted over, which Tuttle notes carries more than a touch of irony. “I always think, ‘Isn’t this in line with Nancy Reagan and Just Say No?’” The press at the time thought the same, and then-Mayor Ed Koch, “who was a real crusader against graffiti and vandalism at this time, realized that maybe there was an opportunity here.” Haring was invited to repaint the mural, and the playground was eventually renamed the Crack Is Wack Playground.

Crack Is Wack marked what Tuttle calls “a shift from the unauthorized to the authorized” when it came to public art that wasn’t necessarily sanctioned by the city, opening the doors to street artists.

Tilted Arc by Richard Serra. Credit: Susan Swider

Tilted Arc: A major lesson for public art

One of the early controversies about a piece of public art in New York City involved a famous artist who chose the wrong venue for his work.

Richard Serra was a well known and respected American sculptor, but his 1981 work Tilted Arc caused an uproar when it was unveiled in Lower Manhattan’s Federal Plaza. Typical of Serra’s works, Tilted Arc was a long, bending wall meant to evoke geometric harmony and attract more people to the area. “But to a worker who doesn’t know the work of Richard Serra, there’s suddenly a wall bisecting the plaza that you traverse every day to get into your office,” Tuttle explains.

There was no advance notice or dialogue with the community, “and so you have a moment where art and the public are at cross purposes,” she says. “What should’ve been a great piece of art in a totally democratic space became something alienating.”

The work was eventually removed in 1989 and remains in a warehouse. “It was instructive to a lot of artists in terms of doing some groundwork in advance beyond just the form and shape and physical organization of the space.”

The Alamo by Tony Rosenthal, 1967. Credit: Getty Images

The Alamo: Too beloved to be temporary

Arguably the most popular piece of public art ever erected in the city is The Alamo, better known as The Cube that sits in Astor Place. Tony Rosenthal’s work was part of a large outdoor exhibition called Sculpture and Environment in 1967 with works all over Manhattan, but is the only piece that remains.

“It was really popular and it became an icon for Astor Place,” Tuttle says, noting that people loved The Alamo because it could be rotated and turned the plaza around it into a hangout.

Tuttle recalls when it was removed for cleaning and conservation in November 2014, “there was this uproar on the internet. It’s back now and better than ever, but there was this sense that this thing had been taken from us.”

“It was not meant to stay, and it just stuck,” she says. “It was like, ‘How could we imagine Astor Place without that cube?’”

Tribute in Light, 2002. Credit: Getty Images

Tribute in Light: Healing a broken city

While public memorials are not necessarily considered public art because they “serve a slightly different purpose,” there is one example of artists creating an impromptu work that helped New York City when it needed it most.

Beloved since its debut in 2002, Tribute in Light consists of two powerful beams representing the World Trade Center towers that are lit up in Lower Manhattan every year on the anniversary of the Sept. 11, 2001 terror attacks.

“Talk about stepping into a void during a period of not just rawness but controversy in New York City,” says Tuttle, referring to the prolonged debate over what the permanent memorial should be. “A collection of artists [John Bennett, Gustavo Boneverdi, Richard Nash Gould, Julian LaVerdiere and Paul Myoda] came together to create an incredibly simple and incredibly powerful tribute.”

Even though the Trade Center site has been rebuilt, including two reflecting pools where the towers stood and a museum commemorating the tragedy, Tribute in Light continues, “which is a testament to the way in which something that is artist-driven and maybe more improvisational than some public artworks can persist.”

The Gates by Christo and Jeanne-Claude, 2005. Credit: Getty Images

The Gates: Raising the bar for public art

Christo and Jeanne-Claude’s ambitious project to place 7,500 saffron-colored gates throughout Central Park was 26 years in the making. Originally proposed in 1979, The Gates were turned down because the city was just crawling out of a huge fiscal crisis and in a dire state of disrepair. “The park needed some serious rehabilitation, and it just felt impossible,” explains Tuttle.

“There was also this argument that was made that the park is itself a work of art, so why impose another artist’s vision on top of that work of art?”

But when Michael Bloomberg took office as mayor, in a post-9/11 New York City that needed the morale boost, the project was finally realized in 2005. “There was definitely something about the experience of people streaming into the park on that gloomy February day, taking pictures, the process of dropping the saffron curtains on each gate,” Tuttle recalls. “There was something very social, community-based aspect to it that is an important part of remembering that show.

“What it did, too, was kicked off a new era of bold, ambitious, gutsy public art in public spaces that New Yorkers have now come to expect.”

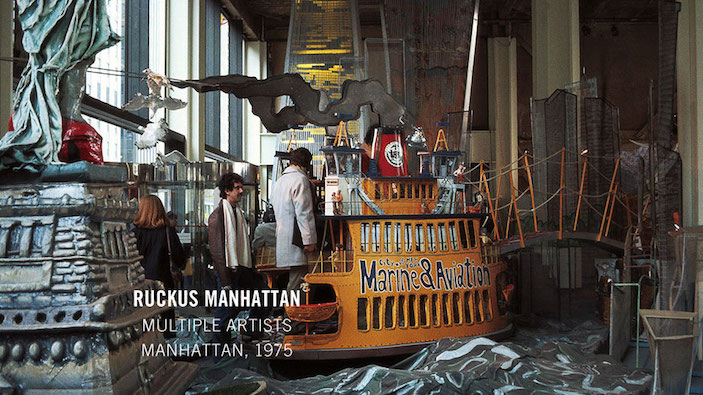

Ruckus Manhattan by Red Groom and Mimi Gross, 1975. Credit: Creative Time

Ruckus Manhattan: Revitalizing a neighborhood

Born from one of the “bleakest moments in the city’s recent history,” it’s not a stretch to say Ruckus Manhattan revitalized an entire neighborhood.

In the boom times of the ‘60s and early ‘70s, Lower Manhattan underwent a renaissance, with tons of gleaming office buildings and commercial spaces opening up. But a massive recession put an end to the boom and created a glut of vacancies. In comes an artist collective (some of whom would go on to form Creative Time) asking the owners of 88 Pine St., whose entire bottom floor was unrented, to stage a series of installations.

Ruckus Manhattan by Red Grooms and Mimi Gross wasn’t the first piece, but it was the most significant. Tuttle describes it as “a fanciful, groovy kind of recreation of New York City,” a 3D “model” that invited people to walk among cartoonish city streets, bridges and subways, where a clothesline hung between the World Trade Center towers and Godzilla was snacking on the Woolworth building.

More than 50,000 people came to see it, and the exhibit traveled around the city afterward. “It speaks to the improvisation and really impressively novel thinking that was in the early stages of the public art movement,” says Tuttle.