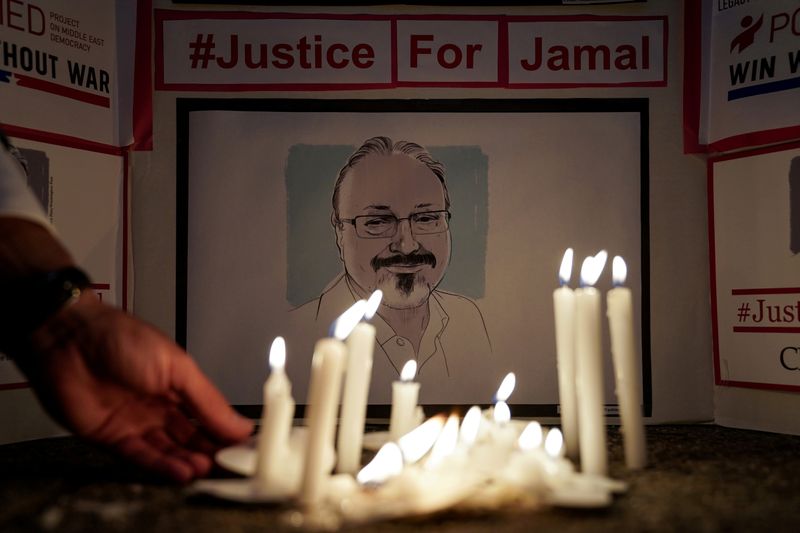

LONDON (Reuters) – When Saudi journalist Jamal Khashoggi was killed in 2018, London-based hedge fund manager Dominic Armstrong bet investors would be turned off and the kingdom’s debt would take a beating.

His fund Horatius Capital made a bet worth millions of dollars through credit default swaps – or insurance against sovereign default – that Saudi bonds would be hit.

But investors largely stuck with Saudi debt.

When the United States declassified an intelligence report last month that said de-facto Saudi leader Crown Prince Mohammed bin Salman approved the operation to capture or kill Khashoggi, Armstrong again thought investors would act.

“I was expecting to see investors very quietly vote with their feet,” Armstrong told Reuters. “People merely holding their nose was not enough. But I think the mood has changed. What will now follow is the actions to back that up.”

He’s still waiting, though.

In fact, demand for Saudi euro-denominated bonds was so strong last month that investors paid to lend the kingdom money.

Riyadh rejected the U.S. report as false, while the crown prince has denied involvement in Khashoggi’s killing. Saudi Arabia is nonetheless the focus of criticism from campaign groups and some Western politicians over its record on human rights and civil liberties.

Yet the world’s largest oil exporter, which has issued about $80 billion in international bonds since 2016, has an A-minus credit rating and pays higher yields than similarly rated peers, making it hard for investors to stay away.

For all the hype and billions of dollars globally pouring into investing based on environmental, social and governance (ESG) factors, it is a niche play in the sovereign bond market.

Some investors say that taking a principled stand on sovereign debt, and financially penalising countries for their record on issues such as human rights could prove counter-productive by constraining modernisation.

“Emerging market debt is full of trade-offs, and taking a Western lens on that sometimes is relatively difficult as they are on a different scale of the development,” said Marcin Adamczyk, head of emerging market debt at NN Investment Partners, which manages 300 billion euros ($358 billion).

Adamczyk did not change his holdings of Saudi debt in the immediate aftermath of the U.S. report’s publication.

Some of the biggest names in ESG investing, including BlackRock Inc, PIMCO and Ashmore, held a total of nearly $1 billion of Saudi debt, based on the latest data for 2020. They declined to comment when contacted by Reuters about the impact of the Khashoggi report.

A Saudi finance ministry spokesman told Reuters that the kingdom was “going through significant transformation which provides multiple opportunities for investors around the world”.

“Investors are still expressing strong interest in Saudi Arabia as witnessed by the recent issue of the Eurobond at negative interest, of which many asset managers have placed Saudi debt issuances in their ESG funds,” he said.

He added Saudi was developing regulations and legislation to improve ease of doing business, increase transparency and support its commitment to the U.N. Sustainable Development Goals as part of its push to improve ESG.

BOND MARKET LAGGARDS

Sovereign debt is part of a fixed-income universe that is a laggard in the ESG game.

ESG fixed income funds operating across the $130 trillion debt market have just under $300 billion under management; by contrast ESG funds across the $88 trillion global equity realm command nearly $1 trillion, Morningstar data shows.

China, a large A+ rated sovereign market that pays 3% yields, is another country where increasing Western investment in sovereign debt is seemingly at odds with European and U.S. criticism over alleged human rights abuses, which are denied by Beijing.

Foreign investors hold more than 2 trillion yuan worth of Chinese government bonds (CGBs) for the first time, with holdings standing at a record 2.06 trillion yuan ($318.7 billion) at the end of February. That was a 3.1% rise over the previous month, the slowest rate of growth since last June.

The Chinese foreign ministry did not respond to a Reuters request for comment.

In a survey last month of dedicated emerging market investors, JPMorgan analysts found that while most agreed that engaging with the issuer was a critical principle to any ESG strategy, more than half of those surveyed had failed to do so with respective state debt management offices.

Still, some investors said it is possible to take a stand. A group of fund managers, for example, have in recent months warned Brazil’s government they will divest their investments unless it halts the destruction of the Amazon rainforest.

Brazil’s Foreign Minister Ernesto Araujo acknowledged this month that there was illegal deforestation occurring, but said his government was combating it, and that it was open to international cooperation on sustainable investment in the Amazon.

Brazilian Vice President Hamilton Mourao said in December that the government had deployed the military to fight deforestation and that further measures were planned, adding that it had to work within tight budget constraints.

On the other hand, realism prevails for investors; the United States is one of the world’s biggest polluters and withdrew from the Paris Climate Agreement during the Trump administration but it is also the world’s largest issuer of debt, making it difficult for fixed income funds to avoid.

‘REALMS OF GEOPOLITICS’

Adding to the complex picture, some investors say the “S” and “G” factors of ESG are far tougher to measure and act upon in sovereign bonds than in corporate bonds or shares.

Some investors also say that focusing on social and governance considerations would heavily favour richer countries, which tend to get a higher ranking than poorer countries because of stronger markers on political stability, educational standards, poverty rates and their labour market.

“In terms of risk assessment, the environmental side is sort of the easy part,” said Eric Ollom, head of emerging market corporate debt strategy at Citi. “The other parts – Social and Governance – get tricky.”

“The Social would be political freedom, and press freedom and social welfare,” he added. “These issues get more difficult to measure and they also cross into the realms of geopolitics.”

Fund managers apply their own weights for working out a country’s ESG score but also factor in the assessment of others. The JPMorgan ESG fixed index, for example, uses the scoring of Sustainalytics for part of its assessment.

Sustainalytics ranks Saudi Arabia, an absolute monarchy which restricts religious, sexual and some other freedoms, 159 out of 172 countries on its ESG scorecard. It had already factored in the 2018 Khashoggi killing, which it lists as an example of “State Repression”, before the release of the U.S. report.

European asset manager Candriam does not have Saudi Arabia in its 882-million-euro sustainable emerging markets fund, which mainly focuses on the environment, because of the kingdom’s carbon footprint.

But it told Reuters that even significant improvements on the environmental front would not change its stance because the country scores in the second percentile on the Human Rights and Civil Liberties component of the fund’s analysis, even lower than its greenhouse gas emissions score.

GRAPHIC: Saudi CDS and oil – https://fingfx.thomsonreuters.com/gfx/mkt/oakverkwkpr/Saudi%20CDS%20and%20oil.PNG

(Additional reporting by Dhara Ranasinghe, Gwladys Fouche, Essi Lehto, Jacob Gronholt-Pedersen, Colm Fulton, Davide Barbuscia and Marwa Rashad; Editing by Jason Neely, Carmel Crimmins and Pravin Char)