The “poor door” at Northside Piers separates affordable housing tenants from people who pay market rate. Credit: Bess Adler, Metro

The “poor door” at Northside Piers separates affordable housing tenants from people who pay market rate. Credit: Bess Adler, Metro

The revelation that a new luxury apartment building on the Upper West Side was approved last month to include separate doors for its market-rate residents and affordable housing tenants has touched a nerve in a city squeezed by higher and higher rents.

Extell Development’s massive project at 40 Riverside Drive isn’t the first in New York City to include a so-called “poor door” or exclude lower-income tenants from certain amenities, but it is the latest and most egregious example of a pattern that critics say treats lower-income tenants as second-class citizens.

New York City Council Member Jumaane D. Williams and Assemblymember Linda B. Rosenthal created an online petition calling on Mayor Bill de Blasio to “end affordable housing discrimination.”

As of Sunday, the petition had nearly 3,000 signatures, with one signee calling the existence of poor doors “a form of government-sanctioned racism and classism.”

“Taxpayer money is being used to subsidize segregationist housing policies,” Williams and Rosenthal wrote in the Change.org petition. “All while wealthy developers continue to benefit from loopholes in the law to increase their profits.”

But according to the Department of Housing Preservation and Development, which approved the 40 Riverside Drive development under the Inclusionary Housing Program, characterizing these sorts of projects as taxpayer-funded is incorrect.

The program offers incentives to market-rate developers to include affordable housing units in return for a zoning bonus which, for example, might allow them to build higher than would otherwise be allowed. No subsidies or city funds are involved.

While these incentives have been effective in creating more affordable housing units, they have also led to the phenomenon known as poor doors — the perfectly legal, but largely unintended consequences of a paragraph of text in the zoning code aimed at requiring developers to intersperse affordable housing units with market-rate units in the same building.

For this requirement not to be triggered, units must be in separate buildings, as zoning law defines buildings. One of those requirements is separate entrances.

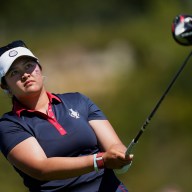

Another project that has drawn intermittent public ire since it was completed in 2007 is Northside Piers, a condominium development along the waterfront in Williamsburg. Just behind the towering building is 20 North Fifth, its affordable counterpart which lacks a doorman and has a noticeably less gleaming lobby.

While the two buildings share a block and a developer, Northside Piers has a number of amenities, including a gym and a pool, that affordable tenants lack.

A longtime tenant of 20 North Fifth, who requested not to be identified so as not to risk upsetting his landlord, said his family lucked out when they landed their apartment, for which they pay $900 a month.

“My wife hit the lottery with this place,” he said. “Top floor, we have a view of everything.”

The lack of access to amenities doesn’t particularly bother him, he said, noting that his neighbors are paying a premium for the privilege and he can always use the gym at work.

Toll Brothers City Living Division, the development company, could not be reached for comment but President David von Spreckelsen has previously described the division as based not on income level but on keeping owners and renters separate.

Because big developments take a number of years to get off the ground and this particular piece of zoning law only went into effect under the Bloomberg administration, it is likely the city will see more of these sorts of projects before the law can be changed, City Hall spokesman WIley Norvell said, noting that it’s too late to do anything about 40 Riverside Drive, which is both a done deal and — when all is said and done — legal.

“We oppose so-called ‘poor doors’ and will change the city’s zoning laws so that when inclusionary housing is provided on-site, we will not allow separate entrances based on income,” Norvell said.

The de Blasio administration, which has set a lofty goal of creating or preserving 200,000 units of affordable housing over 10 years, has been planning to address the issue of separate housing entrances since long before the latest round of public outrage, Norvell said. The process of changing the zoning law is expected to take about a year.