Officers will check for language and formal training

Some officers have also been known to apply an unusually high standard of review of the candidates’ qualifications in an apparent attempt to find lawful grounds for refusal.

To me, it is perfectly understandable that a Canadian might prefer to have their child or elder parent looked after by a close relative rather than by a perfect stranger.

This is assuming, of course, that the prospective caregivers are equally qualified to deliver the needed care.

However, I tend to cringe whenever I am asked by Canadians if they can sponsor a relative under Canada’s Live-in Caregiver Program (LCP).

The technical answer to the question is “yes,” they can sponsor a relative under the LCP since there are no provisions in our immigration regulations which preclude this.

A live-in caregiver is legally defined as a person “who resides in and provides child care, senior home support care or care of the disabled without supervision in the private household in Canada where the person being cared for resides.”

This definition clearly does not exclude nannies that are related to their prospective employer.

Additionally, the program requires caregivers to have:

• The equivalent of a Canadian high school diploma;

•Six-months of formal in class training in a field or occupation related to the proposed employment, or one year of full-time paid employment (including at least six months with the same employer) in the three years immediately preceding the day they apply under the LCP; and:

•The ability to speak, read and listen to English or French at a level sufficient to communicate effectively in an unsupervised setting.

Again, these requirements do not preclude relatives from applying. The departments’ policy manual also does not contain such exclusion.

Yet, experience has shown that such applications are often viewed with suspicion by visa officers which, in turn, make these applications more susceptible to refusal than the norm.

Officers sometimes refuse these cases on the grounds that the family ties suggest that the application is being made solely for the purpose of “facilitating” the applicants’ entry to Canada.

Some officers have also been known to apply an unusually high standard of review of the candidates’ qualifications in an apparent attempt to find lawful grounds for refusal.

And yet other officers have held that the family ties precluded them from being convinced that the applicant will return to their country of origin notwithstanding a Federal Court ruling in 2005 that “there is nothing in the Act or Regulations to prevent family ties between future employer and employee” and that “the caregiver program specifically provides that these individuals can apply for permanent residence afterward.”

Unfortunately, recent experience continues to reveal refusals on the identical grounds thereby necessitating further litigation, costs and delays.

It seems to me that some direction to the field must be given by our immigration minister to ensure that qualified candidates are not refused simply because they are related to those for whom they will be providing care.

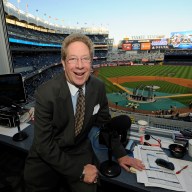

Guidy Mamann is the senior lawyer at Mamann & Associates and is certified by the Law Society as an immigration specialist. Direct confidential questions to metro@migrationlaw.com