There is more than one way to make it to the big leagues.

For Diego Ettedgui, playing baseball in his native Venezuela was his passion, but it wasn’t his future.

“I could catch the ball, I had good range as a center fielder, I was fast, but I could not hit for my life,” Ettedgui said with a grin. “I joke with my family and friends; as a kid I wanted to be a baseball player. Obviously I didn’t have the skills to do it but I tell my parents, ‘I made it, I told you I’d make it.’ There are other ways to make it to the big leagues.”

After a 2016 rule made by Major League Baseball required a designated translator in every locker room, Ettedgui is living his dream.

He travels with the team. He hangs out with the team. And he talks to the team — in his native language.

And he is able to — most importantly — help a slew of talented young Spanish-speaking ballplayers better acquaint themselves with living in a non-Spanish speaking country.

“I felt pressure when I started because I was under the impression that I had to say exactly every single word the players said but it doesn’t have to be that way,” the 29-year-old said. “As long as you get the message across, that’s the important thing.”

Ettedgui got his start as a student at Northeastern in Boston, covering the Red Sox for a Spanish-language publication.

“When I would go to cover Red Sox games, before they had translators, an American journalist would ask a question to a Latino guy and I had to translate it,” he recalled.

Looking just as excited to be in a MLB locker room as any prospect or rookie, Ettedgui transitioned from his job with the Red Sox to various other Spanish-related sports media jobs, most formative of these translating an entire TV show from Spanish to English every football season (for a show called “Totally Patriots”).

More than 24 percent of major leaguers on rosters this year come from predominantly Spanish-speaking countries, with 11 Phillies hailing from Central and South America.

“I love it,” Ettedgui said. “I love it because not only are the guys Latino, but six of them are from Venezuela where I am from.”

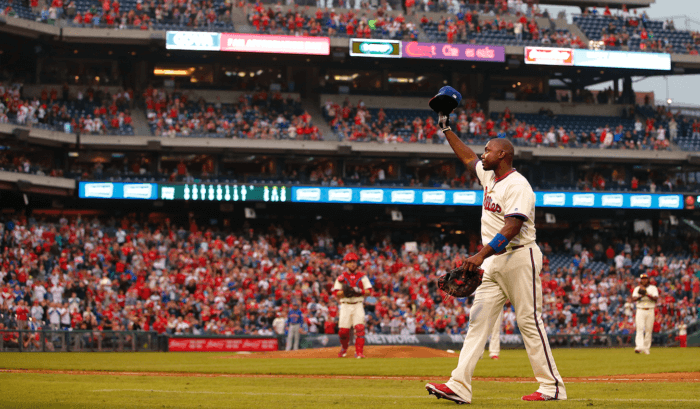

When the Phillies start to compete for World Series titles once again, it will be names like Odubel Herrera, Maikel Franco and Cesar Hernandez popping champagne corks.

And translating their jubilation — he hopes — will be Ettedgui, right along with them.

But first, the Phils need to make strides and start competing again.