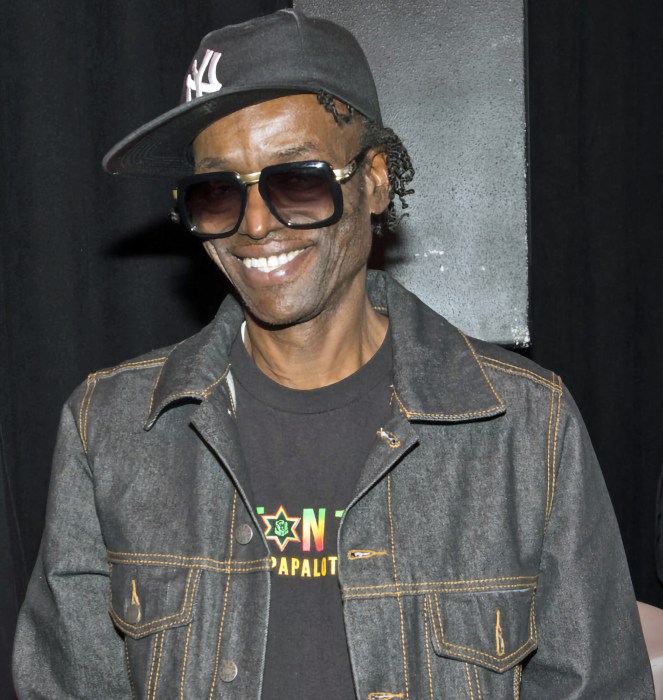

Hubert sits on his walker in front of a downtown grocery store.

“Spare some change, buy a paper?” he calls out, holding an Outreach newspaper tucked behind a Tim Hortons cup. He’s got bushy eyebrows and a moustache, more grey than brown, his weathered skin is wrinkled around his thin, 64-year-old frame. He smiles a lot — one of those toothless smiles of grandfathers after they’ve taken out their dentures.

“What can I get you today?” I ask. It’s either milk or peanut butter. Always is.

“Well, I don’t have any milk,” he replies, and there’s that smile. No need for details — I know he likes the homogenized kind.

George Orwell once argued that begging was a job like any other. “Quite useless, of course — but, then, many reputable trades are quite useless,” he wrote in Down And Out In Paris and London. While salespeople sell and writers write, a beggar is simply a businessman, whose work involves standing outside in all kinds of weather, getting varicose veins and chronic bronchitis. (Hubert got pneumonia twice last winter.)

I’ve often wondered why people who rip us off for a living often command respect. Or why those who collect funds for charitable causes are honoured, while others who fundraise for themselves are shunned.

“I think people realize I’m doing the best I can,” says Hubert.

Alcohol put him on the street, but he’s been clean for 15 years. He now lives in a rooming house, covering the rent with a regular cheque from the government. He can’t get a “real” job because of his chronic seizures, among other things. So he sells the paper. Which is really just an excuse to beg.

In the morning, Hubert is the “Good Morning! man” at Yonge and King streets. One particular businessman stops to chat and gives him a $20 bill every Monday morning — a regular customer.

Now it’s his afternoon shift outside the grocery store, and Hubert is getting tired. Business is slow and he keeps looking up at the Ryerson clock tower to see how much time is left.

Like every businessperson, Hubert has his marketing strategies. For a while, the store would close an entrance at 6 p.m. “I’d call out to the people and say, ‘You can get in over here!’ I’d get their attention,” he explains, smiling, “and more money.”