Rye is tailor-made for a renaissance in our modern world.

The grain, a close relative of wheat and barley, was the base of the first liquor to be distilled in the New World. Low in gluten and high in soluble fiber, it’s cropping up in products like ice cream, Gun Hill Brewing’s Hamilton-inspired Rise Up Rye beer and kvass, a Russian tonic made from rye bread at Enlightenment Wines in Williamsburg.

But the real star is rye whiskey, which will take center stage at the first ever New York Rye Week, with public events like tastings of New York-made whiskeys, a rye-fed pig roast buffet and more going on Oct. 20-22.

The spirit distilled by no less than George Washington was all the rage since the Colonial Era — until it wasn’t. So how is it making a comeback? We asked Allen Katz, co-founder of New York Distilling Company in Williamsburg and host of Rye Week.

The rise of rye

Rye is a hardy grain that endures the harsh conditions of upstate New York winters, so it’s often used today as it was hundreds of years ago as a cover crop. “And farmers don’t necessarily have in mind the economic value of it, they just know that it will maintain their soil as a winter crop,” says Katz.

The Colonials — many of them Scottish and Irish — saw good properties in rye and made it the first spirit to be distilled in North America, and a wildly popular one at that. In 1862, when the first real cocktail manual was published called the Bon Vivant’s Companion, “If you look at the recipes of that era, the American whiskey that you see most often in these recipes is rye.”

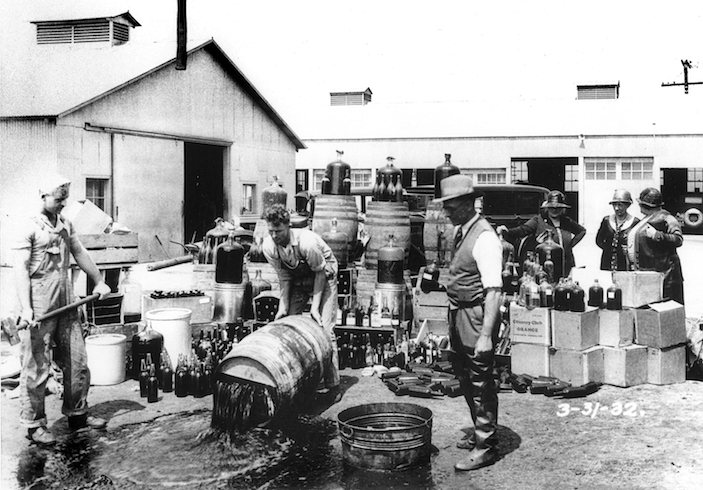

Orange County Sheriff’s deputies dumping illegal booze in Santa Ana, 1931. Credit: Wikimedia Commons

Then came Prohibition

The Great Experiment that was Prohibition hurt all liquor producers, but the rye whiskey industry never recovered. But it wasn’t the ban on liquor from 1920-33 that killed it, in Katz’s opinion. That happened because of changing American tastes that turned to lighter spirits and bourbon, which uses more corn for a sweeter flavor profile.

To win back customers, rye whiskey producers at the time rushed to put out a cheaper whiskey that people can drink every day. “And it was 180 degrees the wrong thing to do,” says Katz. “People said the quality is not there anymore, and they stopped buying rye.”

The comeback

According to Katz, the sea change that has brought rye back into the spotlight happened with an unlikely event: the opening of iconic Berkeley restaurant Chez Panisse in 1971.

“That is the beginning of Americans reclaiming their tastebuds,” he says. “And it’s taken this long for us to have a renewed appreciation for flavors that aren’t based in sugar and corn syrup.”

In are dark chocolate, bitter and herbal flavors — even sour mix used to be more sweet than sour. When New York Distilling opened in 2012, Katz was seeing “an interest in the celebration of the pleasure of spice and notes that denote herbal and earthy qualities, and I would say a greater sense of balance.”

The locavore movement in wanting to eat and drink local didn’t hurt, either, as well as the speakeasy craze that began in 1999 that looked back at the century-old recipes when rye whiskey was venerated.

“And that’s why we’re focused on rye,” he says. “I love bourbon, I love a variety of whiskey, frankly, but we’re really enthusiastic about being part of the reclamation and renewed celebration of rye whiskey as a resolute American spirit.”

What you need to know

Since 2009, rye whiskey revenues have risen from slightly over $15 million to more than $106 million in 2014, according to the Distilled Spirits Council.

When New York Distilling was starting out, there were maybe dozens of independent distilleries in the U.S. — today, Katz estimates there are easily 1,200. His team mashes, ferments and distills their own spirits, including the successful Dorothy Parker gin and their signature whiskey, Ragtime Rye, a blend of 3-to-5 year-old whiskeys.

Unlike their whiskey/whisky cousins in Ireland and Scotland, youth is not a disadvantage for rye whiskey. While the market for aged rye is white hot, you don’t have to wait that long to get the flavors it became famous for.

The key is what makes rye whiskey unique: By law, it must be made with a minimum 51 percent rye mash.

“Rye grain, I believe, is distinctive because it does have a spicy, malty note that comes out in prevalence when you have it as a considerable part of your mash,” Katz says.

Whiskeys from Kentucky, while delicious, tend to contain only the legal minimum of rye, he notes. Raising the amount of rye adds a “bolder, spicy, almost racy quality” — Ragtime Rye contains 72 percent, while other whiskeys go up to 100.

“We weren’t going to release it until it had a simple factor: a new American whiskey that tastes of more than just wood,” Katz says.

“What we like most about our rye is, in our opinion, the time in the barrel imparts a wonderful aromatic, honeyed nose, so before you get to the spice quality of the rye, there’s this luscious, round, pleasant, almost floral quality that is rare among all ryes that we’re familiar with.”

How to drink it

Katz prefers his rye whiskey neat. For the rest of us, bartenders have the tools to play around to highlight specific parts of the whiskey.

That said, “If you’ve never had it before, I can highly recommend a Manhattan,” says Katz. “It’s straightforward enough that no matter what vermouth or bitters you used, you will taste the components of the whiskey.”

Then he recommends moving into cocktails like an Old Fashioned or a Rye Whiskey Sour that are still fairly simple, but bring out different sides of the whiskey.