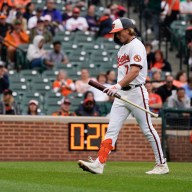

Oscar Isaac (with tabby cat) plays a struggling, penniless folk musician in ’60s Greenwich Village in “Inside Llewyn Davis.”

Oscar Isaac (with tabby cat) plays a struggling, penniless folk musician in ’60s Greenwich Village in “Inside Llewyn Davis.”

Credit: Alison Rosa

‘Inside Llewyn Davis’

Directors: Joel and Ethan Coen

Stars: Oscar Isaac, Carey Mulligan

Rating: R

5 (out of 5) Globes

The Coen brothers are never entirely upbeat, and they’ve certainly been gloomier than “Inside Llewyn Davis.” Both “Burn After Reading” and “A Serious Man” lack hope, even more than “No Country for Old Men” — and that’s a Cormac McCarthy adaptation. But “Llewyn Davis” is pretty bleak. Its titular hero (Oscar Isaac) is a folk singer in the ‘60s Greenwich Village scene, and he’s as uncompromising as he is unpleasant. Both explain why he doesn’t have a home. Penniless, he couch-surfs night to night, eternally exploiting the goodwill of an ever-dwindling circle of colleagues, confidants and benefactors.

Hope is dangled cruelly in front of him: The folk scene is taking off. But the masses like upbeat or pretty music, neither of which describes his miserablist dirges. (There’s a terrific running gag about how all downbeat folkies own big boxes of unsold solo records.) There’s no green pasture for him, and no real plot — just a vicious circle of backslides and humiliations. Llewyn floats through his life like a sleepy-eyed ghost, dealing with abuse, both verbal and physical, both unearned and earned. When not dealing with angry exes (including Carey Mulligan, who speaks to him exclusively in insults), he deals with the various tabby cats put accidentally under his care.

The Coens have been alleged with hating their characters. The charge isn’t unearned. They take clear enjoyment in punishing Llewyn. Whatever doesn’t kill him only keeps him just barely alive to be tortured. As in the Coens’ most recent work, the only gods are the filmmakers. And they’re in a sadistic mood.

But as with their other films, their perspective is more complex than that. Llewyn is often unlikable, but he’s impossible to hate. There’s an admiration for Llewyn’s keeping to principles. If the Coens really hated him, they’d make him talentless. Llewyn is not talentless. He’s terrific. He’s just not remotely commercial. His music is deeply soulful, expressing the anguish of a short lifetime of failure and a slow realization that happiness, of any kind, will always be elusive.

What transpires is very funny. It’s funny-funny, as when Llewyn sits in as a session man on a poppy number that includes Adam Driver (“Girls”) whooping ridiculous backing vocals. And it’s pitch black funny. Llewyn’s stomped dreams become increasingly amusing, especially a drawn-out hail mary that builds to a killer punchline. But his failures are also crushing; more than any film, it captures the frustration of trying to make it in an impossible business during a wintry economic (and otherwise) climate. One can watch “Inside Llewyn Davis” as a sad (albeit often pitch black funny) drama or a hilarious (albeit often sad) pitch black comedy.