WASHINGTON (AP) — One morning during the debt ceiling crisis, House Speaker Kevin McCarthy climbed onto his mountain bike and took a ride along the National Mall, marveling at the monuments.

The next day he arrived for negotiations at the Capitol carting in tortilla chips and queso for the beleaguered reporters waiting outside his office during the 24/7 talks.

McCarthy, with his laid-back California vibe, was never Washington’s bet to become speaker, having almost missed seizing the gavel in a history-making spectacle at the start of this year.

But the 58-year-old is now leading House Republicans in the high-wire act of his career: Having negotiated a deal with Democratic President Joe Biden over the weekend to raise the nation’s debt limit, he now must deliver the votes to pass the spending cuts package into law.

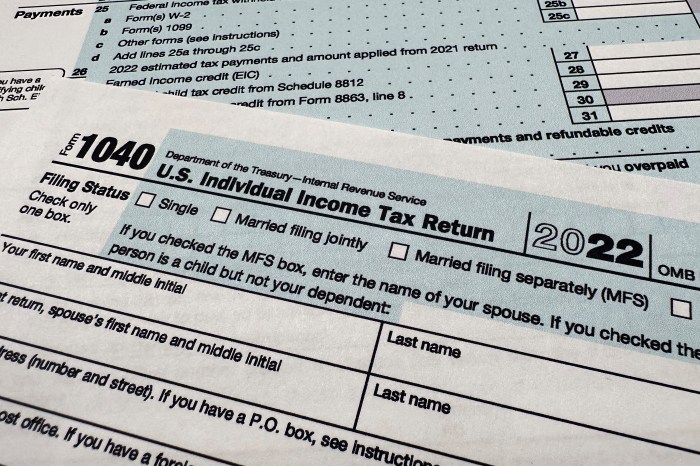

The standoff is being watched the world over as the United States stares down a June 5 deadline when it could run short of cash to pay its bills, potentially hurling the American economy into chaos with an unprecedented default and taking the global economy into a crisis.

McCarthy commands only a slim majority in the House and must reach out to Democrats to support the compromise. But neither side is expected to be happy with the final agreement reached Sunday between the president and speaker.

If McCarthy succeeds in pushing the budget-cutting deal through Congress, it will be an accomplishment like nothing he has achieved before. Or he could lose it all, if the compromise he reached with the Democratic White House becomes so objectionable to the conservative flank that Republicans try to oust him from his job.

“One thing you’ve always learned about me: I don’t give up,” McCarthy told reporters as he arrived at the Capitol on Saturday morning.

“Doesn’t matter how many times it takes,” he went on, “you want to make sure you get an agreement worthy of the American public.”

Throughout the weeks of grueling negotiations McCarthy has remained relentlessly optimistic, breezing through the anxiety-filled hours, seemingly certain of the outcome.

Underestimated from the start, he is nothing if not relentless. To become speaker, McCarthy endured 14 failed votes before finally securing the gavel on the 15th try, only after he had tired his colleagues out and given hard-right conservatives all sorts of promises and concessions.

McCarthy isn’t known as a seasoned legislator, one who has delved deeply into policy details or put his name on many big bills.

Having arrived in Congress in 2007, he rose swiftly to leadership as a political strategist, not a policy wonk.

Younger than the previous generation of congressional leaders, McCarthy is decades younger than Biden. The president has been in elected office since McCarthy was a young man growing up in dusty Bakersfield, running a sandwich shop counter from his uncle’s yogurt shop and becoming immersed in Reagan-era politics.

The White House refused initially to engage with McCarthy over the debt ceiling, insisting Congress must simply do its job, raise the nation’s debt limit and skip the political brinksmanship.

Powered by a hard-right flank, McCarthy was determined to extract federal spending cuts to programs many Americans rely on in exchange for the votes in Congress needed to raise the nation’s debt limit.

McCarthy laid down a marker in his first meeting with Biden back in February. The new Republican speaker refused to raise any taxes to help offset federal deficits, including Biden’s proposals to roll back some of the Trump-era tax breaks for the wealthiest Americans and corporations.

The White House ultimately relented on negotiating with McCarthy after he pushed the GOP’s preferred debt-ceiling plan through the House, uniting his majority for the talks to come.

Democrats argue the showdown over the debt limit should not be the new normal way of doing the nation’s business.

Despite pleas from progressives, Biden has been reluctant to invoke powers under the 14th Amendment to raise the borrowing capacity on his own, unconvinced of its legal soundness.

The debt ceiling fight is not one that Congress needs to take on, and historically it was rarely like this. Often a routine endeavor, the vote to lift the debt limit, now $31 trillion, would allow the Treasury Department to keep paying the bills without any risk of default, ensuring America’s standing as the world economy with the most trusted currency.

Once Republicans seized power in the House during last year’s midterm elections it was almost certain a debt ceiling showdown would land at Biden’s doorstep. It was that way the last time Republicans swept into power, in 2011, on the tea party wave that launched the new era of brinksmanship in Washington, using the debt ceiling as leverage.

But these showdowns have tested GOP leaders as well, bedeviling past Republican speakers unable to fully satisfy the party’s increasingly conservative wing.

The hard-right House Freedom Caucus chased one former speaker, John Boehner, to early retirement. Another speaker, Paul Ryan, left office after a short term.

To become speaker, McCarthy worked hard to appeal to those same forces, agreeing to revive a House rule that allows any single member to call for a vote to oust the speaker. Forcing him from office would require a majority vote.

That threat hangs over McCarthy at every step as he tries to manage a debt ceiling deal.

Conservative Rep. Dan Bishop, R-N.C., warned in a tweet Saturday, before the deal was announced, that if the speaker brought back a “clean” debt ceiling increase, meaning one lacking the party priorities, “it’s war.”

But even if conservatives grow frustrated with McCarthy, he still has one important voice in his corner: former President Donald Trump.

As one of the earliest backers of Trump’s first White House bid, McCarthy has tried to stay close to Trump despite their on-again, off-again relationship. He said they spoke in recent days and Trump told him, “Make sure you get a good agreement.”

Associated Press writers Stephen Groves, Mary Clare Jalonick, Kevin Freking and Farnoush Amiri contributed to this report.